“Radical Hope” – an exhibition of works from Collection II owned by the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok – part of the UK/Poland Season 2025

“Radical Hope” – an exhibition of works from Collection II owned by the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok – part of the UK/Poland Season 2025

Artists: Hubert Czerepok, Zhanna Kadyrova, Diana Lelonek, Lada Nakonechna, Marina Naprushkina, Konrad Smoleński, Piotr Uklański

September 13th – November 8th 2025

Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast

Curator: Monika Szewczyk

Co-operation: Peter Richards

Co-ordination: Sarah McAvera, Mary Stevens, Eliza Urwanowicz-Rojecka

Owned by the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok, Collection II is one of Poland’s essential contemporary art assemblages, representative for the Polish art scene of the past thirty years as well as for Eastern Europe. The Collection II concept has been developed to an open corpus concept – a solid foundation for our efforts to build multifaceted narratives in an attempt at describing the reality we live in.

While not our direct experience, the war in Ukraine, frozen protests in Belarus, crowds filling the streets of Tbilisi are phenomena we can certainly identify with. Our existence has been imprinted with a sense of threat – multiple threats, actually – a sense of helplessness, and awareness of a certain time coming to an end, of the gradual decline of an order we recognised as formative.

The exhibition title references Radical Hope, a book by Jonathan Lear. In his foreword to the Polish edition, Piotr Nowak claims the book to be responding to three fundamental questions:

“(1) How does one live in a world which has suddenly lost all sense? (2) is hope at all conceivable in such a world?; if yes, (3) which language should be used to express it?” This approach to hope extends beyond regular expectations of improving a given situation or resolving specific issues; it is an idea of profound transformation. Following Lear’s intuition: in order to exit existential impasse, we need a guide capable of noticing new meanings, new capacities within. Can such role be entrusted to art? Can artists anticipate as yet inexistent solutions through their commentaries on reality?

Events:

- Saturday 13th September 1-3pm – Exhibition Launch

- Friday 19th September 5-10pm – Culture night Belfast 2025

Curatorial text by Monika Szewczyk

Collection II at the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok is one of the most significant contemporary art collections in Poland. It not only reflects the Polish art scene of the past thirty years but also engages with some of the most compelling developments in Eastern European art. Conceived as an open collection, it serves as a foundation for creating multifaceted narratives that seek to make sense of the reality we live in. Collection II brings together works created during and after Poland’s political transformation, as well as the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union, and the regained sovereignty of its former republics, including Ukraine and Belarus. The early 1990s were a time of profound change, and even greater hope. For Polish art, it was a period of inspiration and reassessment, as artists began to embrace the idea of art as a critical tool for social change. But is such change even possible? Today, that question seems harder to answer than it did thirty years ago. What can we say now about the world we live in? Can the language of art help us understand it better, make it easier to accept? Can we come to terms with it enough to feel a little safer?

We live on the edge of madness, in a constant, multifaceted crisis that fuels tensions on both global and personal levels. We find ourselves helpless, and increasingly indifferent, as we witness the war in Ukraine, a war waged against civilians. We have been speaking about it for three years now, though in reality it has been unfolding in hybrid form since 2014. The brutally suppressed protests and political prisoners in Belarus have almost faded from memory. We watch civil disobedience on the streets of Tbilisi and Belgrade, or riots in Paris, and these are only examples from our immediate surroundings. The entire world seems consumed by conflict, whether through ongoing wars, deepening divisions or the rise of extremist movements. Even the shared threat of the climate crisis has failed to bring about a sense of cooperation or dialogue. It feels as though there are no safe places left. Those who migrate in search of safety often encounter hostility and rejection. We may not experience this first hand, yet we can relate. In both Belfast and Białystok, we understand what it means to live on edge and to feel under threat. Sharing experiences of conflict can become an important force for connection, sparking reflection. We live with a constant sense of danger, or rather, of many overlapping dangers. We carry a feeling of helplessness and the awareness that time is running out, that the order which shaped our world is disappearing. Many believed that World War II would be the last catastrophe of its kind, that we would never forget and never dare to repeat it. Today it feels as though we are standing at the threshold of another global conflict. After the war, the return of fascism seemed impossible. Yet now it’s spreading once again, its reach growing ever wider.

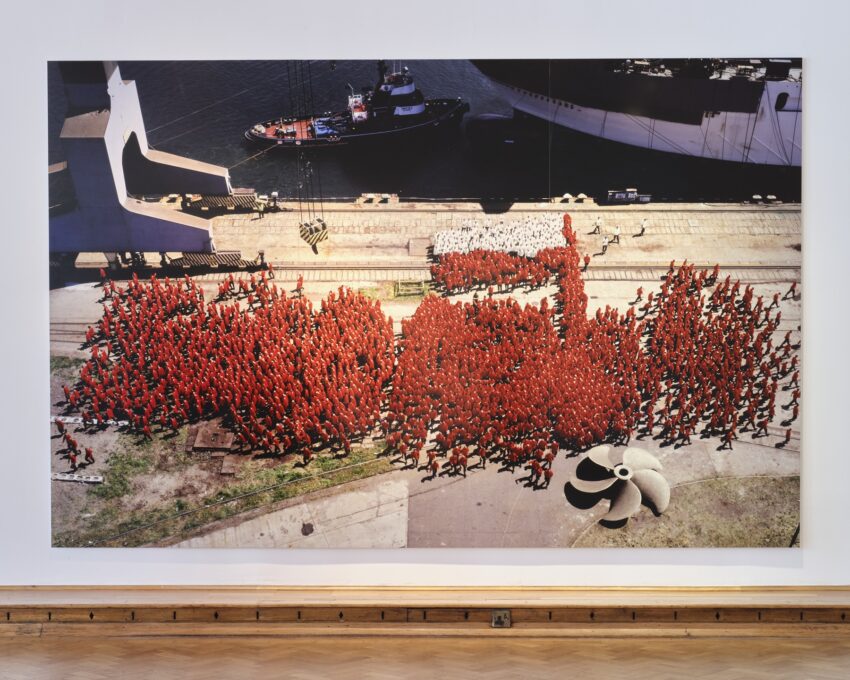

It hardly seems likely that art could save us from all this, but perhaps it can still teach us something. In the works on view, the artists explore themes of solidarity and cooperation, as well as fractures in the social fabric, as seen in the work of Piotr Uklański. They examine the dangers posed by fundamentalism, highlighted by Hubert Czerepok, and remind us of the devastating consequences of totalitarianism, as reflected in Zhanna Kadyrova’s work. Konrad Smoleński addresses feelings of alienation and entrapment in the face of reality, while Diana Lelonek warns of the looming climate catastrophe. Lada Nakonechna sheds light on the issues of refugees and undocumented migration, and Marina Naprushkina exposes fear of the Other as both a political resource and a tool of control. Between the lines, questions emerge about democracy, about agency, about our readiness to take responsibility and about the strategies we choose in order to survive.

In his book Radical Hope, which lends its title to the exhibition, Jonathan Lear reflects on how to live in a world that has lost its meaning, drawing on the story of the North American Crow tribe. He asks how we can find hope in such a world and how we can express it. This approach to hope goes beyond the simple expectation that circumstances will improve or that problems will be solved. It speaks instead to the idea of profound transformation. Following Lear’s intuition, we need a guide to help us emerge from existential impasse, someone who can see within the crisis a new field of possibilities. In the past, we might have assigned this role to art, believing that artists, by commenting on reality, anticipate solutions that do not yet exist. But can we still place that responsibility on them today? What, then, do we base our hope on? And to what extent can we still call it radical?

Translated from Polish by Anna Bergiel

Curatorial text by Peter Richards

Radical Hope: Art at the Edge of Uncertainty

Hope is not a luxury—it is a necessity. It is not passive. It is not escapism, nor a denial of the present’s complexity. Rather, it is a radical act: the courage to imagine a future not dictated by the inertia of the past. In an age saturated with curated distraction and commodified crisis, to hope is to resist despair and envision a more humane alternative.

Curated by Monika Szewczyk, Radical Hope brings together selected works from the Arsenal Gallery, Białystok, Collection II—one of Poland’s most vital contemporary art collections, representing three decades of artistic engagement with the shifting cultural and political landscapes of Poland and Eastern Europe. The exhibition explores the role of art in cultivating what philosopher Jonathan Lear calls “radical hope”—a hope that endures even when the frameworks of meaning have collapsed.

The works on view do not offer easy answers. Instead, they confront unresolved historical fears—colonial, racial, ecological—and ask: how do we begin to articulate a solution when the rules are breaking down and language itself is destabilized?

Marina Naprushkina’s Your Fear – Our Capital. Your Hate – Our Mandate draws from her work with refugees, exposing fear as a tool of social control. Her practice reframes fear not as a private emotion but as a systemic force—engineered, circulated, and weaponized.

From fear to false promises, Hubert Czerepok’s Lux Aeterna interrogates the enduring legacy of 19th-century utopianism. His work reveals how rational ideals can mask extreme violence, reminding us that the past is not past—it is perilously close, embedded in the architecture of the present.

Diana Lelonek’s Forms of Survival shifts the lens toward ecological collapse. Her speculative installations imagine the future of cultural institutions in a world unraveling. Can art remain a site of resistance and renewal when the infrastructures that support it are themselves in crisis?

This question reverberates in Zhanna Kadyrova’s Shots series, where cracks in ceramic surfaces—beautiful yet brutal—speak to the trauma of war and the seductive ambiguity of aesthetic form. Her work captures the violence of abstraction, where meaning fractures under pressure.

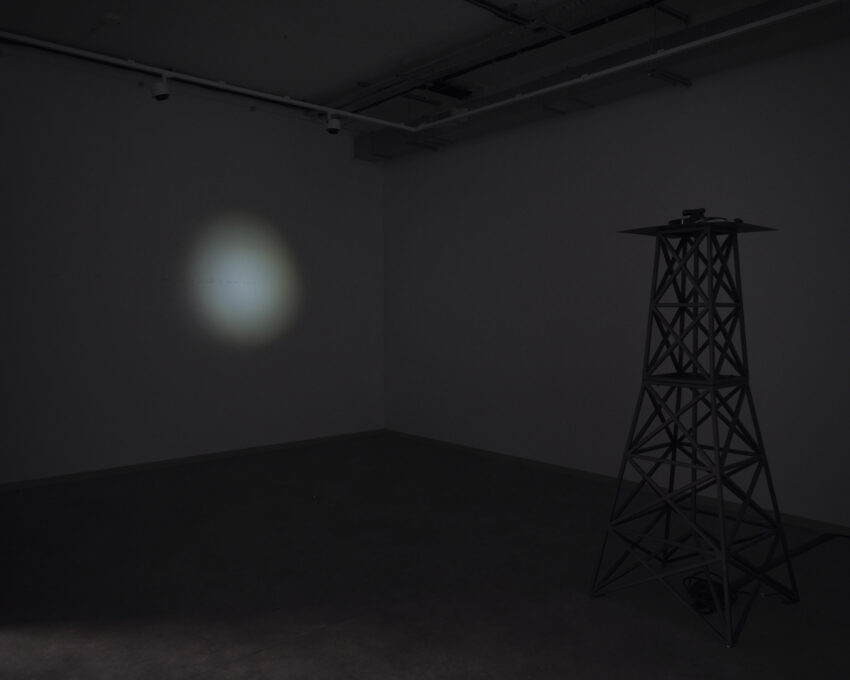

Konrad Smoleński’s The End of Radio turns inward, reflecting on alienation in the digital age. If a broadcast has no listener, does it still exist? His work becomes a metaphor for the breakdown of communication and the isolation of the individual in a hyperconnected yet dissonant world.

The erosion of collective ideals is further explored in Piotr Uklański’s Untitled (Solidarity). As the iconic logo disintegrates, so too does the illusion of unity. Uklański’s piece questions the endurance of political symbols and the fragility of shared narratives.

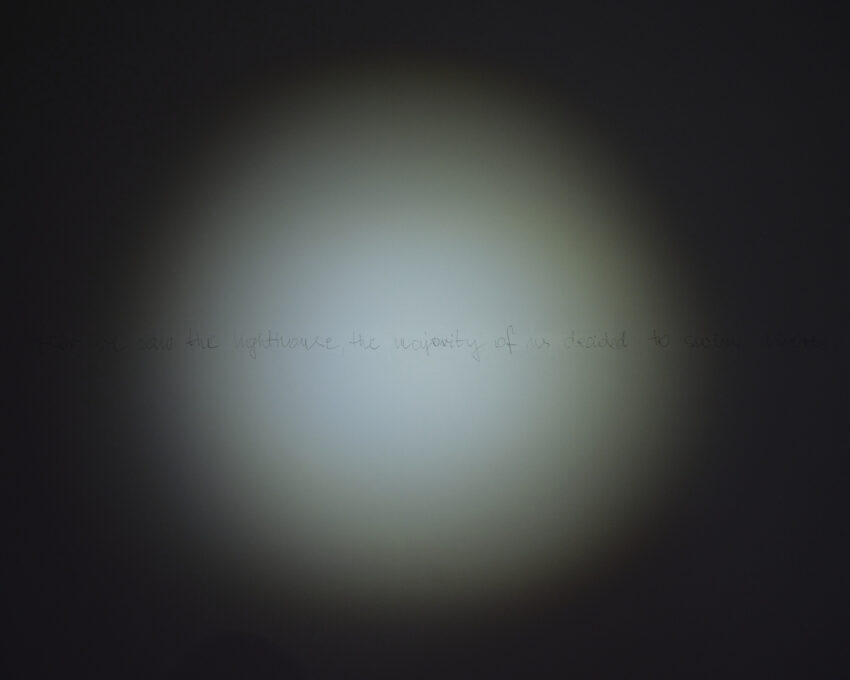

Lada Nakonechna’s Mobile Portable Model brings to the exhibition an illuminating search for security—economic, political, and existential. Her work becomes a guiding light, exposing the stark realities of displacement while holding space for the possibility of belonging.

Together, these works do not merely reflect the world—they offer glimpses of how we might reshape it. They insist that even when language fails and systems falter, the ethical imperative remains: to speak, to imagine, to build. Radical hope, then, is not a distraction. It is a compass.

The future is not written. It is shaped by the stories we choose to tell, the solidarities we choose to form, and the courage with which we choose to hope.

The Adam Mickiewicz Institute (IAM) brings Polish culture to people around the world. As a state institution, we create lasting interest in Polish culture and art through strengthening the presence of Polish artists on the global stage. We initiate innovative projects, support international cooperation and cultural exchange. We promote the work of both established and emerging artists, showcasing the diversity and richness of our culture. We also run the Culture.pl portal, a comprehensive source of knowledge about Polish culture.

Culture.pl is the largest and most comprehensive source of knowledge about Polish culture, run by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute (IAM). We provide reliable information about the most important phenomena and trends in culture, as well as events organised in Poland and abroad. Here you will find profiles of artists, reviews, essays and expert analyses that portray the richness of Polish art. We publish in eight languages, bringing Poland’s contribution to global culture and humanistic heritage closer to an international audience.

Organisers:

Adam Mickiewicz Institute

Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast

Arsenal Gallery in Białystok

The event is part of the UK/Poland Season 2025 organized by the British Council, the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Institute of Polish Culture in London, funded by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Poland.

ORGANISERS:

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30