Childhood dream

“Every child born has, at the moment of birth, a greater potential intelligence than Leonardo da Vinci ever used.(…)’. [Glenn Doman]‘Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up’. [Pablo Picasso]Every child born has, at the moment of birth, a greater potential intelligence than Leonardo da Vinci ever used. [Glenn Doman] Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up. [Pablo Picasso] The idea for the exhibition “Detsky sen” originated from a fascination with childhood. Childhood (especially the first years of life) is the period when the young human being learns the fastest; the brain is the most open and ready to absorb the largest amount of data.

This results from the fact that a child’s brain is very plastic and can be formed very easily. Detailed knowledge of the related processes is due to research in neuroscience, a discipline that evolved in the late 20th century, which, in turn, gave rise to neurodidactics, also known as brain-based learning. One of the pioneers of neuroscience, the American psychologist Michael S. Gazzaniga, described his discipline as being about learning how the brain creates the mind. Initially, the interest in neuroscience as applicable to pedagogy or child psychology resulted primarily from the need to explain various development deficiencies in children; ones which affected, for instance, the leaning process. Soon, however, conclusions drawn from research in neuroscience began to be applied in investigating the stages of brain development, and the potential for stimulating it, in the entire population of children. This was the case of Glenn Doman, an American physiotherapist and the creator of the global reading method, which he initially applied in the rehabilitation of brain-injured patients (mainly children and teenagers); later he broadened his field of interest to include the early education of healthy children. This was because he discovered that the learning mechanism remains unchanged regardless of whether his method is used with healthy or deficient children. What is more, research and practical knowledge led him to the conclusion that since the growth and development of the brain is a dynamic, variable process which can be arrested under the influence of various external factors, it can just as well be accelerated. During one of his lectures at the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential in Philadelphia, Doman asserted that an environment rich in varied stimuli was more crucial to the development of the brain and to its efficiency than genetic heritage. The conclusion arising from this is that every individual should from birth live in an environment that would stimulate all biological processes responsible for the development of the brain and the nervous system. The more external stimulation there is, the denser the neural network will become; an impulse can therefore be conveyed by means of various networks. This makes the processes of learning, drawing analogies, understanding phenomena and making comparisons easier and broadens the perspective. Research has shown that formation of neural networks is largely influenced by experience and environment. It is the environmental impulses that shape a person’s experience and thus affect the growth of new neural circuits.[i] “Childhood occupies a special position in the life of any human being. It lasts for only a few years, but in no other period of life do this many transformations occur in such a short interval. If for the sake of argument we assume that our life lasts for about a hundred years, the first years of it take up just a few percent of it. Yet if we look what changes occur in any subsequent period of our lives, we shall see that in no other period are these changes equally fast, equally wide-ranging or equally significant (…)”.[ii]

In his extensive study entitled Centuries of Childhood. A Social History of Family Life,[iii] the French historian Philippe Ariés presents the ways in which childhood was perceived in Western societies from the Middle Ages until the modern period. From this study we learn about the position of a child in the society and the family, the expectations held towards a child, and the changes the perception of a child and childhood over the centuries. The perceptive analysis conducted by Ariés is based principally on iconography. In his opinion, in the Middle Ages childhood did not have a specific place and people did not have a sense of its distinctiveness. Until the 12th century, medieval art ignored childhood altogether, not treating it as a discrete period of human life. A child that no longer needed the constant care of a mother or a nanny simply entered the adult world and naturally lived side by side with the grown-ups. A child’s needs were not a subject of reflection, because childhood was not perceived as a separate developmental phase. Until the end of the 13th century children were shown in art as small-scale adults devoid of any childlike traits; the only feature that distinguished them from adults was height. The only exception is the image of Child Jesus, the predecessor and model for all the infants and young children in the history of art. Its evolution towards a more realistic and more emotional depiction of a child is evident relatively early. 13th-century painting featured also the images of an angel and a child saint.

This manner of representing children does not mean that in the Middle Ages children were not loved. They were, of course, cherished; they were perceived as small, amusing creatures and adults would play with them as they would play with pets. Ariés observed: “In medieval society the idea of childhood did not exist; this is not to suggest that children were neglected, forsaken, or despised. The idea of childhood is not to be confused with affection for children: it corresponds to an awareness of the particular nature which distinguishes the child from the adult, even the young adult”.[iv] But the very high child mortality rate made it reasonable not to get attached to an infant or a toddler. As a rule, its death was not a cause for concern; the deceased child was soon replaced by a new one. A child remained somewhat anonymous. Hence the emergence, in the 16th century, of the portrait of a deceased child as a specific genre is considered to have been a milestone, as it indicated a change in the approach. The next breakthrough was the emergence of the portrait of an unaccompanied child; this happened in the 17th century. Before, if they were featured in portraiture at all, children appeared in family portraits together with their parents. The putto invaded art slightly earlier, still in the 16th century; the naked little boy became a popular decorative motif. It is symptomatic that the image of a putto emerges and develops almost at the same time as child portraiture. From the 17th century onwards childhood occupies a special place in genre painting: scenes showing children during reading, drawing or music lessons are very numerous indeed. An analysis of the iconography from the Middle Ages until the 17th century clearly reveals that childhood was gradually being discovered and singled out as a separate developmental phase linked with specific needs. The interest in the psychology of children and the desire to explore their mental capabilities increased parallel to these discoveries.

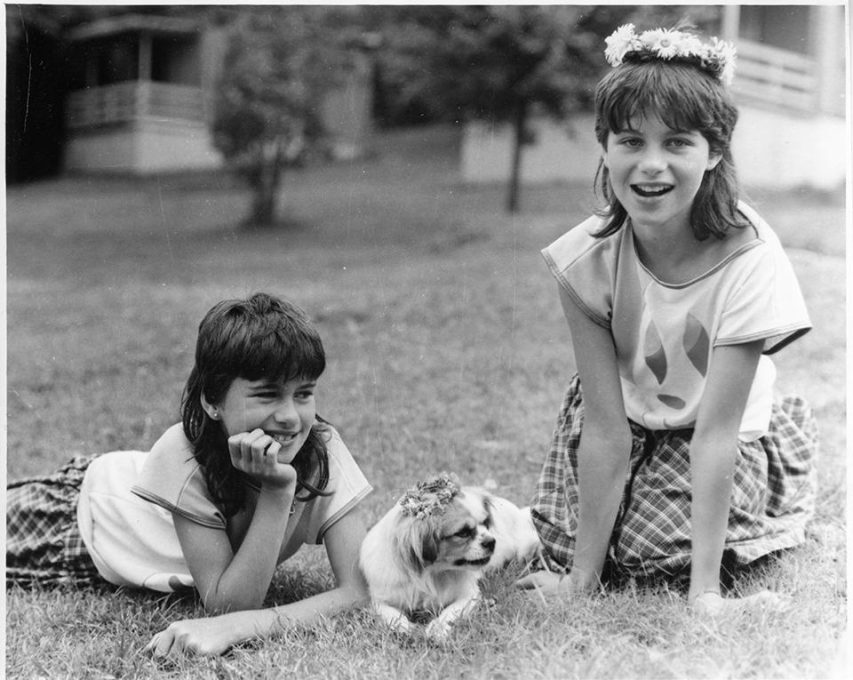

The topic of the exhibition “Detsky sen” is childhood. Does a person’s childhood influence their adult personality? As adults, where do we place – often subconsciously – our childhood experiences and the memories of our young years? The title of the exhibition originates from the title of the artwork by the Slovak artist Lucia Nimcova, which, in turn, refers to a boat in which the 11-year-old Lucia and her friends sailed in a downriver cruise organised annually in her home community. The “Detsky sen” enterprise had been initiated by the local photographer and cultural activist Marián Kusik. The communally built boat – or, to be more precise, a raft house – had its walls made of large-format photographs by Kusik, showing the crew. In 2010 Nimcová decided to repeat the “Detsky sen” enterprise. Having been invited to an exhibition in Prague, she arranged a remake of a situation from over twenty years before. Lucia Nimcova’s work represents a return to childhood memories and their recreation in adult life. Such early experiences are of great importance, since they may affect a person’s adult life in a very decisive manner.

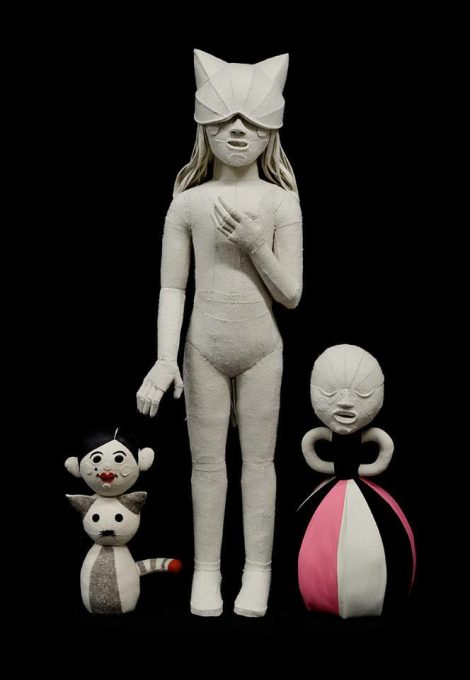

The exhibition “Detsky sen” touches upon the subject of free, uninhibited development and the role of creativity in stimulating cognitive and imaginative potential. Culture is the stimulus activating children’s cognitive curiosity. The courage to create is also developed during childhood. This process of creation, or creativity itself, ought to be understood not only in terms of art, but more broadly, as they manifest themselves in every aspect of the human life – learning, professional work, social roles, etc. The German sculptor and performance artist Joseph Beuys, who authored many artistic theories, e.g. the expanded concept of art, defined the role of creativity as vital. In his view, it was an essential quality of human beings and their actual capital. Beuys’s principal motto was: each man is an artist. The expanded concept of art stipulates that each person possesses artistic potential which may be developed and which gives them the possibility to alter reality. In his Psychologia twórczości [Psychology of creativity], Edward Nęcka draws attention to an egalitarian approach to the category of creativity, regarding it as a latent characteristic of human beings, one that pertains to their potential rather than to actual “works”.[v] In Nęcka’s approach, artistry (or creativity) is the process that leads to the creation of new, valuable and useful objects (things) and ideas. Contacts with culture initiated during childhood broaden a person’s cognitive horizon, expanding their creative potential, which, in turn, shapes their cognitive openness, acceptance, courage, activeness, non-conformism and other traits.

The fact that the development of a child is heavily influenced by adults cannot be disregarded. Assuming that adults are guiding children through the process of exploring the world, they ought to encourage the four fundamental competences of a child: courage, the sense of security, autonomy and imagination. If we care about building a democratic society as a common good, it is imperative that we stimulate the development of such characteristic as openness, activeness, critical thinking, courage and non-conformism. For such a society to form and develop, children must be treated as individuals capable of acting and thinking, and allowed to grow with the awareness of personal sovereignty and the responsibility for their actions.

Continuing this train of thought, let us refer once more to Centuries of Childhood. At the beginning of the modern period two new concepts emerged, namely the belief in the inferiority of childhood and the sense of moral responsibility for children taken on by adults (parents, teachers). With the introduction of organised education, which, at least in Europe, was a manifestation of a great moralisation movement undertaken by Catholic and Protestant reformers, parents began to take interest in their children’s education and follow their progress. They assumed moral responsibility for their offspring, which was usually related to the adoption of an authoritarian discipline, in terms of both moral and corporeal punishment. Similar practices were also used at schools. Ariés wrote: “The history of discipline from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century enables us to make two important points. First, a humiliating disciplinary system – whipping at the master’s discretion and spying for the master’s benefit – was substituted for a corporate form of association which remained the same for both young pupils and other adults […] In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries corporal punishment became widespread at the same time as an authoritarian, hierarchical – in a word, absolutist – concept of society”.[vi] The same phenomenon is aptly illustrated in Michael Haneke’s movie The White Ribbon (2009), whose plot is set in Germany before the outbreak of the First World War and depicts the cruelty of children brought up in the spirit of constant humiliation and subjected to “moral correction”.

In reference to the above considerations, the exhibition “Detsky sen” tackled the subject of Schwarze Pädagogik (black pedagogy). This term began to be used in late 1970s owing to the eponymous book written by the German author and educationalist Katharina Rutschky.[vii] She defined black pedagogy as “actions aimed at breaking the free will of a child and making it unconditionally subordinate to that of the parents”. The concept of black pedagogy was expanded and described in detail by the Swiss psychoanalyst Alice Miler. In her book For Your Own Good. Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence,[viii] Miller presents the view that the success of totalitarian systems in the second half of the 20th century was greatly influenced by the pedagogy practiced in the late 19th and early 20th century, with its belief in the benefits of corporeal punishment that led to oppressive, cruel and humiliating upbringing. Similar conclusions were drawn by Theodor W. Adorno in his book entitled The Authoritarian Personality,[ix] which presented the results of a research project completed shortly after the end of the Second World War in order to determine the causes of the spread of Nazism in Europe. The theses included in the famous F scale (fascism scale) were largely related to the authoritarian model of upbringing that involved displays of force, i.e. precisely what Rutschky dubbed black pedagogy. According to Adorno and the other authors of the book, the causes for the development of an authoritarian personality lie in conservative methods of child-rearing, such as strict discipline, conditional love or corporeal punishment.

The exhibition “Detsky sen” refers to the problem of black pedagogy in order to point out that childhood is not only a Rousseau-style idyll or a carefree period. It also signifies contact with the practices of educational institutions and the necessity of constantly adjusting oneself to social norms; because this is the basis for the sum total of influences and processes known as upbringing.

Agata Chinowska

[i] E. Szeląg, “Neuropsychologiczne podłoże mowy” [in:] Mózg a zachowanie, ed. T. Górska, A. Grabowska, J. Zagrodzka, PWN, Warszawa 2000.

[ii] A.I. Brzezińska, M. Czub, R. Kaczan, Dziecko przedszkolne. Jakie jest? Jak możemy wspierać jego rozwój?, Instytut Badań Edukacyjnych, Warszawa 2013.

[iii] P. Ariés, Centuries of Childhood. A Social History of Family Life, transl. R. Baldick, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962.

[iv] P. Ariés, op.cit., p. 128.

[v] E. Nęcka, Psychologia twórczości, Gdańsk 2001.

[vi] P. Ariés, op.cit., p 261.

[vii] K. Rutschky, Schwarze Pädagogik. Quellen zur Naturgeschichte der bürgerlichen Erziehung, Ullstein: Franfurt/Berlin, 1977.

[viii] A. Miller, For Your Own Good. Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence, transl. by Hildegard and Hunter Hannum, New York: Farrar – Straus – Giroux, 1983.

[ix] T.W. Adorno, E. Frenkel-Brunswik, D.J. Levinson, R.N. Sanford, The Authoritarian Personality, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950.

Julian Józef Antonisz, Agata Borowa, Olaf Brzeski, Krisztina Erdei, Zofia Gramz, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Eva Kotátková, Tomasz Mróz, Ciprian Mureşan, Lucia Nimcová, Patrycja Orzechowska, Anna Panek, Laura Pawela, Yevgen Samborsky

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30