Monika Weychert Waluszko

Subtle shades of grey breed monsters. As befits shadows

“Who Needs This”? Zofia Gramz juxtaposes ingesting preserves in a very dignified fashion against research of faraway galaxies, love against conceptual art. It would seem that man does not need all these realms to survive: you can satisfy hunger with all elegance abandoned, procreate without love, exist on Earth without sparing a look for stars you would need ten consecutive human lives to reach. A film created specially for purposes of an exhibition at the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok is a display of different activities in contradiction. It is no more than a brief glance cast by the artist at a given area. Scenes cut short bring abstract gestures to mind. Contrary to common belief, it is not the artist who turns out to be the one displaying irrational behaviour. The opposite is true: in contrast to other human activities, creation seems to carry tangible sense…

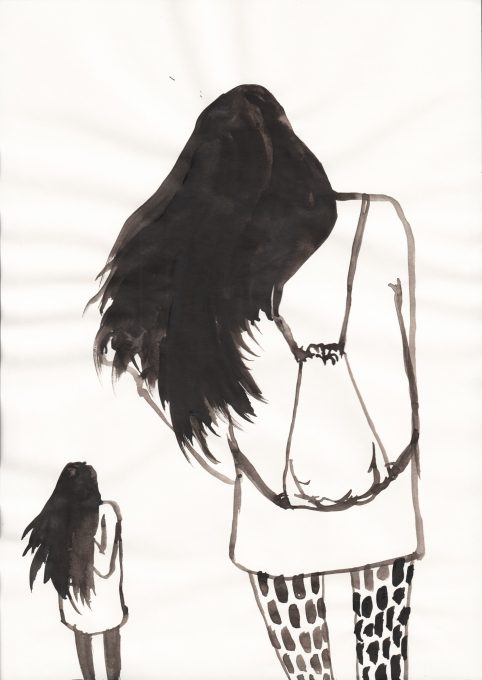

Gramz follows the topos of an “upside-down world”. Her drawings are seeped through and through with carnival logic. Michaił Bachtin outlined the boundaries between regular satirical and carnival laughter. Operating within negating laughter, a satirist positions him- or herself beyond all phenomena mocked. “Carnavalisation” is realised in the equality of different social languages; in free-flowing fiction; in a blend of serious and comical elements, of human and animal qualities; in a presence of vulgar and lofty style alike; in scandalous and iconoclastic aspects; in parody and a certain dose of indispensable sadness. It assumes the lack of any distance between the narrator and world represented. Carnival laughter is total and universal, spanning the world in its entirety, carnival participants included. “The grotesque body,” Bachtin writes, “is not separated from the rest of the world; it is unfinished, unclosed, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits. The stress is laid on those parts of the body (…) through which the body itself goes out to meet the world; this means that the emphasis is on the apertures or convexities, or on various ramifications and offshoots: the open mouth, the genital organs, the breasts, the phallus, the potbelly, the nose. (…)– the body discloses its essence as a principle of growth which exceeds its own limits.” Such works as eklektyczny outfit (the eclectic outfit), chęć bycia takim jak wszyscy (the wish to be like everyone else), zabawa w indian (playing indians), człowiek enigma (the enigma man) could all serve as an illustration of the aforementioned quote. Figures undulate, either pliable or unexpectedly rigid – not always in expected places. Disproportionate limbs extend into infinity, morphing into cripplingly short stumps. Occasionally, drawings are an astonishment in their precision and suggestiveness, spilling into spots, clouds, and inkblots – as in case of przymierzając za ciasne futro (trying on a too-small fur), or the focal figure in Dzień Niepodległości (Independence Day).

Gramz’s work is fascinating in terms of the bond between the greatly coherent, individual vision of the world represented in hundreds of artworks – and the accompanying captions. Importantly, captions form no part of representations created. Yet in a sense, they resemble non-representational thought-paintings by Paweł Susid. “The creation of brief text accompanying an art form and engaging in dialogue therewith has proven sufficiently difficult to render me illiterate. (…) I attach such great importance to the meaning of each word, it is no mean feat for me to write a sentence devoid of subversive text.” Similarly, Gramz’s captions are beautifully phrased, brief, and to the point. They all operate within well-known contemporary matter, in a simile of a media message stream strained through the author’s filter. The filter captures selected slogans, current imperatives, recurring gags, and web memes. Who hasn’t sent internet animals (zwierzęta internetowe) to friends when boredom smothers chat exchanges? Who has no interest in staying current (bycie na bieżąco) by reading web articles, or in checking facebook (sprawdzanie facebooka)? Through their own experience, audiences find it easy to identify with all captions, a certain pleasure derived from the simple process of deciphering embedded messages. Human sense of humour is not subject to will, lying beyond any options of moral judgment. As in case of candy according to Umberto Eco – we have no influence over its taste. Sweet remains sweet, bitter remains bitter. “(…) since, therefore, the Black Corsair weeps, woe to the scoundrel who laughs. Yet woe, too, to the simpleton capable but of being moved. Dismantling the mechanism becomes an imperative. (…)”. Similarly, one can be touched or amused. Gramz’s bon mots will make you smile automatically.

How does the mechanism work? The subversive power of small artworks lies in the tension between the drawings themselves and their linguistic layer. Their drollness stems from two different orders. In a simile to a perfect picture book, image and text cannot exist without one another, yet they retain a certain autonomy. The subjective has been paired with the standard. Everything concealed and unspoken continues pulsing “below diurnal surface” – in synch with what remains omnipresent and daily available to all caption readers. While multiple opinions are offered as to the sources of the comical effect itself, it is generally accepted that its essence lies in the disclosure of surprising discrepancy and contrast resulting from the process of presenting persons and circumstances differing from recipient expectations. Such laughter borders on terror, or profound sadness. To grasp the rule in Gramz’ s work, suffice to look at her Sebastian. The iconic St. Sebastian figure is worshipped by the Church. Yet the cult, having surpassed all expectations of Church hierarchs, was occasionally criticised and believed to be dangerous. This is how Andreas Sternweiler, a theologian from Worms, described the phenomenon in sacral art: “The cult of the figure indicates pagan influence of the ancient cult of Apollo, and the mythical fact of its resurrection. Here we have an attempt of integrating an ancient Greek myth with Christian tradition.” Concurrently, the beautiful martyr became an icon of homosexual desires. Sebastian, shown in agony, enables a blend of sensual experience: death, agony, and suffering fringe on ecstasy in renderings. St. Sebastian is a being inhabiting the borderland of paganism and Christianity, of sainthood and camouflaged sin. Also in Gramz’s art, he is a hybrid: a mermaid and a blasé kid from a fashionable café. Nothing stands in the way of the narcissistic youngster’s self-love, not even the arrows in his abdomen. Yet despite his coquettish posture, the thin body triggers laughter and pity rather than feelings described by Vasari as excessive viewer excitement when confronted with Sebastian Fra Bartolomeo. On the other hand: maybe such is the contemporary martyr? No saint any more, just Sebastian – hostage to omnipresent gender stereotypes.

Carnality is a recurrent motive in the artist’s works. The seemingly quenched mentality of gender-determined categories has been successfully replaced with omnipresent social pressure tying in with socialisation and the teaching of social roles. Today, sexism returns in veiled form: in references to hormonal changes, to advantages determined by gender. While you are entitled to free choice, get yourself a well-known face (zrób sobie twarz kogoś bardzo znanego), remember to optically extend your legs and hide all flaws (optycznie wydłużyć nogi i ukryć mankamenty), go and tan until brown (strzaskana na heban). In any case, you have to attend a Course on Feeling Feminine (Kurs czucia się kobieco) – he, after all, does place his own classifieds: Interested in Cars, Looking for Someone Slim (Interesuję się motoryzacją, poznam szczupłą). Today, Barbie can be a doctor without borders, a journalist, astronaut, computer scientist, professional snowboarder, yet with the perfect figure, make-up, and hairdo. She has to remain eternally younger, fitter, slimmer, and whiter. Gramz displays the circumstances of women and men who find it hard to meet the canon and adapt to raised social expectations.

Gramz’s drawings are filled with fantastical creatures, animals, and monsters. All hybrids have features we can simultaneously perceive as our own and alien. Borderline phenomena, they are marvellous description who we are as a community. “The anomalous is neither an individual nor a species; it has only affects, it has neither familiar nor subjectified feelings, nor specific or significant characteristics. Human tenderness is as foreign to it as human classifications. Lovecraft applies the term ‘Outsider’ to this thing or entity, which arrives and passes at the edge, which is linear yet multiple, ‘teeming seething, swelling, foaming, spreading like an infectious disease, this nameless horror.’” In the film Zdrowie i trzeźwość (Health and Sobriety), the flickering transformation of the Mermaid and the Eagle can be observed over time, accompanied by an exaggerated and enhanced and constantly changing pulse of the city and of history. A) Robal, B) Dwa borsuki, C) Twoja stara (A) Bug, B) Two Badgers, C) Yo’ Mama), a work bordering on a visual puzzle and a Rorschach inkblot test, displays the propensity of the human brain to interpret obscure stains as human face shapes: recognisable while not necessarily friendly. Here we have the Holy Mary born of window cleaning fluid – or is it a monster emerging from a tree trunk? Is this the genealogy of anomalous spectres colonising our mythology? While a world filled with peculiar creatures may be somewhat oniric and mystical, it can also be somewhat trivial, our perception errors weighing it down: such combination strips Gramz’s work of any pretentiousness or pandering to common taste. This is an intelligent and highly sophisticated game involving bestiaries of many eras.

An analysis of solo exhibition titles, one cannot resist an impression that they are Gramz’s confessions, one after another: “I live quietly and I don’t restrict myself at all” (2010), “Health and Sobriety” (2011), “Beard, Moustache, Glasses – No Way to Hide” (2011), “Nothing Happened” (2013), “Co by tu porobić przed śmiercią” (“What To Do Before Dying”) (2015), and, finally, “Who Needs This” (2016). Yet one would be hard-pressed to declare whether what we are facing here is rather an individual or a generational experience. The draughtswoman displays the socio-economic aspects of artistic life – often as not in contrast to the sociological image created outside the art community. Is the wish to be like everyone else a signum temporis representative to the entire group of artists? Or rather an expression of tiredness experienced by this particular individualist? Does her back hurt? Is this how she bade farewell to her Father? Is this how she outlines a target and remains with it? The viewer cannot verify any of these theses. Nonetheless, somewhat subversively, these works bring Teodor Parnicki’s Dzienniki z lat osiemdziesiątych (Journals from the Eighties) to mind. The writer took notes: several dozen words according to a specific code: how much he drank, how many pages of a book he wrote, what he read, whom he talked to. These amazingly modest memos are a record of truth about the difficult – and, ultimately, lost – struggle with alcoholism, the bond between drinking and creativity, depression and weakness of the human body, a writer’s tools, about the source of his research, fascinations, and auxiliary reading, and about the literary world in the People’s Republic of Poland: from publishers to critics, Parnicki’s social life and his uniquely symbiotic relationship with his wife. A mere few lines become a valuable source of knowledge about the whole world in its complex wealth. A simile can be drawn between the writer and the rather enigmatic artworks by Gramz. While this is a diary, it is cleverly problematised by the artist herself. She makes an attempt to control the exact moment of when words begin flowing onto a page, as if during an automatic writing séance. And she herself remains under media pressure so strong, that she is condemned to “rewrite” the surrounding world. “The magnitude of media information is trying to break through, chain the attention with images and slogans that attempt to arouse the strongest emotions. On the other side of the monitor, in a quiet, safe setting, sits a person who on the one hand reacts to everything emotionally, and on the other hand feels powerless amongst the sheer volume of issues. With time, the person becomes indifferent and can no longer distinguish between minor and important matters. (…)”. The topics the artist approaches are numerous and examined in-depth. Some are recurrent as if in a chorus or parts of a fugue. They may be an obsession born of a sense of helplessness and solitude. Or are they no more than the subject of detailed studies?

When taking a look at these works, it would be worth our while to find out whether the mirror offered to us shows lost human beings, hybrids, or monsters. What we perceive as the very essence of life is merely a plaything of an idiot? And “Who Needs This”?

translated from Polish by Aleksandra Sobczak

Bachtin. Dialog, język, literatura(Bachtin. Dialogue, Language, Literature), edited by E. Czaplejewicz and E. Kasperski, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1983.

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949.

Agata Kłocińska, Karnawał wobec sacrum. O ludyczności kultury współczesnej (On the Luddism of Contemporary Culture), in Kultura i wartości, No.3 (2012), pp. 117–134.

Paweł Susid, http://culture.pl/pl/tworca/pawel-susid (accessed on January 16th 2016).

Umberto Eco, Superman w literaturze masowej. Powieść popularna: między retoryką a ideologią (Superman of the Masses. Rhetoric and Ideology in the Popular Novel)(translated into the Polish language by J. Ugniewska), Kraków: Znak, 2008.

Janusz Boguszewicz,Święty Sebastian – patron gejów? (St. Sebastian – Patron Saint of Gays?), http://homiki.pl/index.php/2008/01/wity-sebastian-patron-gejw (accessed on January 16th 2016).

W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Mary F. Rogers, Barbie Culture, London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE publications, 1999.

Natasha Walter, Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism, London: Virago Press, 2008.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 2nd volume of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Teodor Parnicki, Dzienniki z lat osiemdziesiątych (Journals from the Eighties), Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2008.

Marcin Krasny, Bank Pekao PROJECT ROOM. Zofia Gramz. “Nothing Happened”, curator text, http://www.csw.art.pl/index.php?action=aktualnosci&s2=1&id=710&lang= (accessed on January 16th 2016).

Curator:

Agata ChinowskaZofia Gramz