ZDENA KOLEČKOVÁ. In one breath

exhibition leaflet – click to download>>>

BREATHING THE SUDETENLAND

Breathing the Sudetenland has become our fate. It is not our land and at the same time, it is. In other places, the past is naturally passed from generation to generation by means of telling “simple” stories. In a non-pathetic and rather spontaneous way, young people learn from the elderly about who planted a certain tree or built a particular house. These are not history lessons, but home dinner talks, chatting with friends when fishing or over a beer. Often, they can help one understand more about the given place than they could learn from literature or textbooks. Individuals with this kind of roots are then surely better able to grasp the space they are living in, but also to become aware of themselves in the context of the surrounding social ties.

However, all around the Czech border area, there is often no one to be asked these very simplest questions. I experienced this myself when I was growing up, as I come from Liberec. When bummeling about Jizerské hory (the Izer Mountains), almost forestless then due to the apocalyptic environmental disaster, I came across remains of houses, tumbled stone steles bare of crosses, or overgrown and long unused carriage roads between defunct villages. The mountains were so empty and forest workers in the valley pub after the daylong solitude were silent too. They did not know the hills actually, and maybe, they did not like them. They had not been born there and “did not exist” there, just worked.

Nevertheless, it seems that much has changed in the Sudetenland since then. Life is gradually “creeping” in it. Descendants of those who replaced the expelled Germans after the War have slowly taken their roots. To make the land become theirs, they have to reconcile with the painful past, to overlive the past by means of their own present. So re-erected memorials, devotional pillars or conciliation stones again appear along paths, a number of chapels and churches have been repaired, and traditional farming practices return to the meadows at the foot of the mountains. In many places, forests are planted not only for economic profit, but also to be beneficial to people who walk through them. Actually, all these minor, often almost imperceptible signs of restoration are fatally connected with a decision to do things right and above all, in accordance with one’s conscience.

Despite all the practical positive movements, the public discourse is still rather diffident of opening the burning issues of leaving and regaining the Sudetenland for broader discussion. Interconnection of the region with particular life stories is too tight and it is simply not possible to deal with them only at the abstract level of collective perpetrators and victims, decisions and consequences. Such debates simply require personal bravery as they are immediately related to our ancestors and relatives, and sometimes, they may painfully transform our view of the very closest family environment.

These complex and often traumatizing disputations gain an ever broader scope in the context of contemporary art. As if its metaphoric character naturally opened to subjective experience, giving space for catharsis through an esthetic perception, and in a way, also facilitated bringing up particular questions related to the history and present of the Sudetenland at the point of intersection of real life stories to attract more attention of the society.

Zdena Kolečková (*1969) belongs to the visual artists who focus their efforts on both historical and current consequences of the Sudetenland milieu on a long-term basis. Her work grows out of the initiatory experience of a dramatically captivating, yet severely suffering landscape of Krušné hory (the Ore Mountains), as well as of the family background straddled between the Czech, the German, and the Polish lineages. Her mother’s parents spoke German and remembered a lot from the purposely toned down events connected with the War and the post-war displacement. Part of the relatives moved to Germany, others lived in the former German-Polish borderland around Gliwice in Poland. The author was growing up in the desolation of Husák’s real socialism when the economic and environmental exploitation represented by the development of extensive surface mining irretrievably swallowing up hundreds of villages and towns together with a number of their cultural expressions of the original Sudeten ethnicity culminated.

And it was just her utter defiance – necessary to maintain the moral integrity – to these monstrous political manipulations and devastation of human fates and the soul of the landscape cultivated for centuries that directed Zdena Kolečková’s artistic activities towards a reflection of concealed stories of particular places and their inhabitants. This interest started to show up in the author’s works as early as in the mid-1990’s when she participated in first appearances of the generation circle sometimes called “the Ústí neoconceptual school” implementing artistic expression strategies focused on a reflection of a specific social context, especially the borderland postindustrial periphery, in the Czech milieu (exhibitions Disturbed Balance, 1993; Private Anamnesis, 1995; North, 1997).

In her mutually interconnected cycles presented in these exhibitions, Zdena Kolečková thematized issues related to principles of social and political manipulative systems and their manifestations in the structure of urban complexes and the suburban landscape (for instance Wen trifft die Schuld, since 1998; Just a Story, 1999; Luftschutz, since 2005). Later, the author aroused interest with a loose series of works turning into the world of her closest relatives when she visually transposed intimate stories of the family members or documented significant parts of the family heritage in the form of particular objects, archival documents or utterances (Old Recipe, 2001; Triple Identity, 2009; Left by Germans, 2009; Romance, 2011).

The latest works collected in this publication logically develop the already established lines of Zdena Kolečková’s thinking towards a comprehensive and subjectively structured author’s expression. In terms of intermingling fateful destinations of particular places and human fates, we can consider the processual site-specific intervention called Made in Ghetto (2012) and the photographic installation Best Friend (2013) emblematic realizations.

In the first of the mentioned works, Zdena Kolečková turns to one of Ústí nad Labem peripheries called Předlice. It is a sort of a symbol of opposites concentrated in the past and the present of the Sudetenland. In times of the communist regime, the once prosperous prewar industrial and residential locality was destined for extinction as part of the mining allotment for one of the brown coal mines, and today, it is fatally threatened by processes of the economic decline and social exclusion. When reflecting this place, the author explored traditional recipes the original inhabitants of Předlice used to take advantage of the local natural wealth. According to the recipes she had collected, the author picked up various, mostly wildly growing plants in the locality to produce soap, wine, jam, perfume, and other products from them. Then she sent them to a certified chemical laboratory for analysis to make sure they could be consumed without problems. However, most of the products that had been made for centuries did not meet basic hygiene requirements, especially due to the environmental exploitation of the place. In the resulting installation combining the real home products and laboratory reports showing results of individual analyses, Zdena Kolečková pointed out the deep gap between the natural, but violently interrupted coexistence of a place and its original inhabitants, and our unsuccessful efforts to re-inhabit the abandoned space.

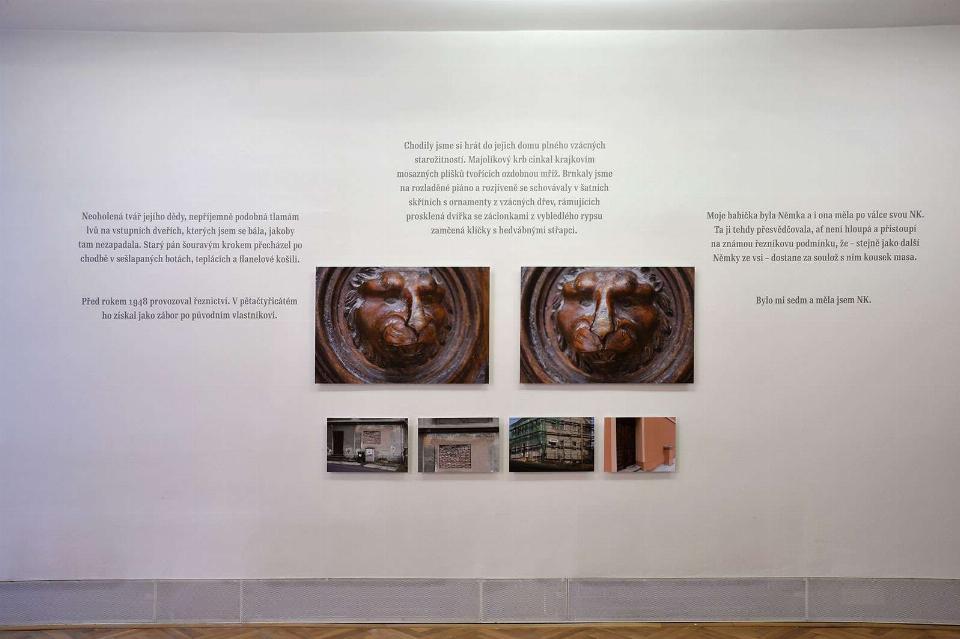

In a seemingly peaceful poetic condensation, the text and photographic installation called Best Friend presents an intense example of an intergenerational conflict resulting from the dramatic political and social changes in the Sudeten environment during the second half of the 20th century. Individual photographs to a certain extend impersonally document the gradual devastation followed by a “decayed” restoration of a particular property representing the character of the Ore Mountains suburban architecture. The narrative line of the work describes a harmonic relationship between two small female friends unexpectedly accelerated by their belonging to the opposite poles of the local inhabitants’ spectrum – the new settlers often motivated by an easy chance to gain the abandoned property, and the small part of members of the original community who had not had to leave, but still were stigmatized by their German origin. The displaced events connected with the failure of basic democratic mechanisms after all again and again assert themselves into the social consciousness in various forms of totalitarian residues, with a potential to devastate it irretrievably at all levels.

The Best Friend project reflects our own imaginations and desires. It cannot be more direct – a defined place, real people, a true and cruel story, a clearly asked question. In many respects, it reminds the framework of the social conflict connected with denazification of Germany at the turn of the 1960’s and 1970’s, which in the cultural sphere was represented for instance by the generational manifestation of authors gathered around the NeueWilde group (JörgImmendorff, Martin Kippenberger, Gerhard Richter, but also for example Hans Haacke). Someone could argue that it is too late now for a critical review of the postwar events, as it has been almost 70 years since they happened. Actually, the contrary is the case, and an unprejudiced discussion related to them will be necessarily connected also with the subsequent period when the communist regime established and reigned over the country. In this respect however, we are still waiting for a discoursive field to open as it is necessary for asking basic questions to determine a broad dialogue in the yet to come generation of historians and politicians.

So what does “breathing the Sudetenland” mean today? Perhaps, it means finding freedom in you to denominate your own position in an unfocused landscape lacking a solid framework of existence. In her artworks, Zdena Kolečková seeks to do this stubbornly and we sometimes get a lump in our throats when “reading” her stories. Only when we are conscious of the outermost corners of the territory we inhabit today, we can find a potential for accepting it once for all, together with those who owned it before us, as well as those who will inherit it after us.

Michal Koleček

Chřibská / Kreibitz (the Sudetenland), November 2013

media patronage:

Zdena Kolečková

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30