Archiwalna

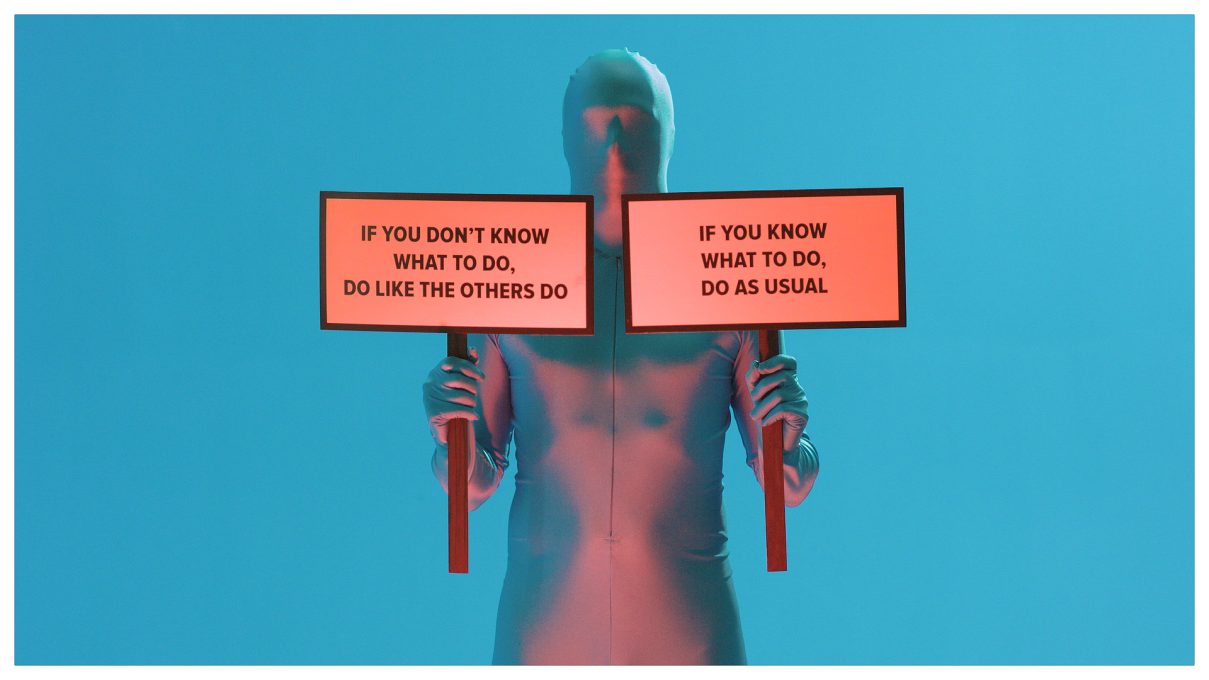

TYMEK BOROWSKI – Everybody needs rules, but each of us needs different ones

15.05.2015 – 11.06.2015

Galeria Arsenał, ul. A. Mickiewicza 2, Białystok

Tymek Borowski: FAQ

(Frequently Asked Questions)

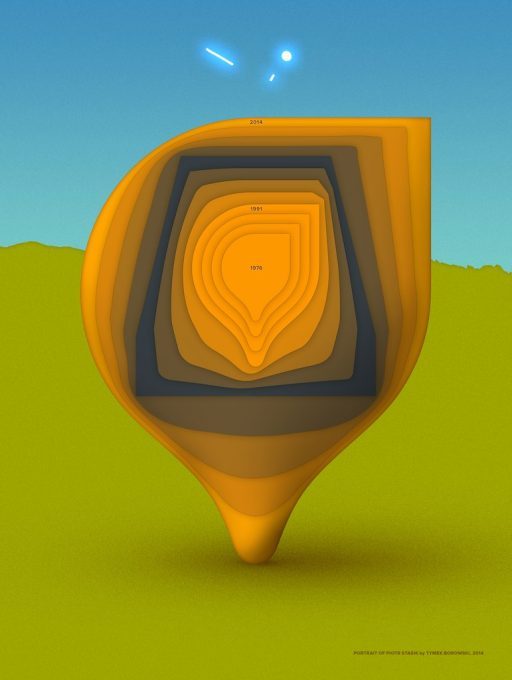

Tymek Borowski is interviewed by Piotr Stasik, a director of documentary films, whose portrait is a part of the exhibition “Everybody needs rules, but each of us needs different ones”at the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok

Piotr Stasik: Can you recall the moment when you decided to devote yourself to art, to painting?

Tymek Borowski:A definite moment would be hard to find. Both of my parents and my older brother had studied painting, so as a topic, it was always close at hand, but as a kid I did not like drawing. I remember that it was only in the middle of the secondary school that I produced my first artworks. I got a computer and already those first works were in Photoshop. My first attempts at traditional drawing I made later, getting prepared for the entrance exam to the Academy of Fine Arts.

And you still produce computer artworks. Doesn’t the computer stunt the spirit?

No. Certainly no. The presence of the spirit is not dependent on the tools used. Computers present a different problem; it is their versatility. On the one hand it is a good thing, because it allows me to switch from tool to tool, from inspiration to inspiration, very easily and to automatise various repetitive actions. But on the other hand, paradoxically, this versatility slows down my work. A universal tool is always less effective than a specialised one.

Your greatest inspirations are…

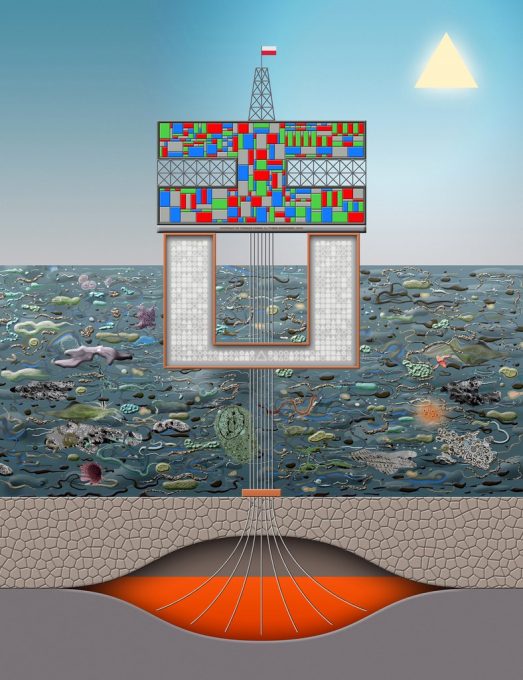

Mainly from outside the world of art. I am interested in the perception of the world from the point of view of science, and so I draw a lot of inspiration from reading popular science. For example, I came up with the film How Culture Works inspired by Steven Pinker’s book The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. When I learn about some theory, some thought, and get fascinated by it, I try to investigate it for my own private use and, in passing, I create its scheme. That’s how many of my works are made.

I draw much inspiration from art, too, but not from the newest, post-conceptual art, but rather from painting. Picasso is the most important to me, I think. He is a treasure trove. Apart from his painting, it is crucial to me that he always followed his interests. He did not heed the requirement to be consistent, he continually changed his style. It is crucial, as my mentor, Professor Leon Tarasewicz, put it, “for the brush to keep pace with the head”.

How does your creative process look like; how do you find topics, how do you self-organise?

I don’t like looking for topics. I try to create conditions in which they find me, they come to my head by themselves. I read and watch a lot, and the topics emerge. It also very often happens that when I am just about to finish working on one thing, the topic for the next work just comes to me. It’s very organic.

I sketch a lot before starting on a work. These are not just drawings, more like notes, schemata, a lot of texts.

When I start painting a picture, it already has a structure that I came up with earlier, the elements I intend to be there, the relationships between them. It is a kind of a script for a painting.

Oh, a script! Here is a feature shared with my working on films. I did not expect that. But how do you implement that script?

The implementation of it is more impulsive. If I planned my work precisely, I would die of boredom. Many elements that emerge that this stage seem irrational on the conscious level. It is impossible to describe precisely why they emerge. It is because that’s how I feel.

Which do you consider more important, thinking or feeling?

Various scientific experiments have shown that if we had no emotions, we would be lying in our beds and thinking up new ways of doing things, reviewing advantages and disadvantages, but we would not have any impulse to action, we would not be able to decide which plan to carry out. This, I think, is very much my case; so I cannot put a dividing line between thinking and feeling.

What are the duties of an artist? Can he transform reality, change other people’s thinking?

I don’t think there are any duties. I don’t have any definite programme of improving the world. I only add my bit and in this way – at least so I hope – I am transforming it a little. This is just as if I were a bicycle manufacturer and were trying to make good bicycles, ones that would ride nicely. This is changing the world for the better, is it not?

I used to have a sense of a mission for a while, but this was emotionally harmful to me. I saw that it was a truly horrible mechanism: people made sacrifices for their mission and then expected a reward from destiny. Such approach may end in a substantial frustration.

How did you come up with the idea of producing portraits? Has anything surprised you in their making?

I am interested in how diverse people’s approaches to life are, in the principles that guide them, in how they construct their own, made-to-measure “cultures” to suit their own innate character. Also, it is an interesting situation: an artwork is being made that is intended principally for one recipient. Only this one person can have such a strong relationship with this work, can consider it truly essential.

And what surprised me? People’s openness, I think; I expected they would be telling me some rubbish, trying to convey a sugared image of themselves. Instead, they tell me a very great lot about themselves, very frankly.

Are you not becoming some sort of a psychologist painter?

More of a documenter than a therapist. My sitters are usually older and more mature than me, so it is rather I that can learn from them than other way round. People are happy to tell stories; this creates engrossing conditions and sharing a conversation is most pleasant. I never draw confessions out by force, but often those chats go really deep, they are truly intimate.

While working, do you wonder what the recipients of your work will think, and do you check this later?

While making the info-graphics, I think a lot about whether the recipients will understand them. I take a long time selecting words, simplifying images and so on. But I am trying not to think about the recipients along the lines of “will they like it?”. If I thought this way, I would feel constrained. When I am creating artworks, I am mindful of liking them myself.

When the works are ready, I am of course very curious what people think about them. I am interested in their critical opinions, too. The input of the haters must be respected as well; but only of the wise ones. Calling attention to all the weak points, the wise haters are doing the analytic work for me, free of charge.

Sometimes I receive some exceptionally pleasant piece of feedback. Recently one gentleman has sent me an e-mail asking for files with the info-graphics which he saw at my exhibition. He wanted to put them up in his home because he thought they could improve his life.

Warsaw, May 2015

translated from Polish by Klaudyna Michałowicz

Tymek Borowski (born 1984 in Warsaw). He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in the studio of prof. Leon Tarasewicz on 2009. As a student he presented his works at solo and group exhibitions. In 2013 he was nominated in the contest Views 2013 and won the audience award. In the beginning he was focused on painting but gradually he expanded the range of media used. He currently creates videos, digital painting and infographics.

Related events:

Please join us to meet the artist on 16 May (Saturday) at 11.00 Galeria Arsenal.

Media patron:

Tymek Borowski

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30