Archiwalna

The Pure Tongue

19.06.2015 – 20.08.2015

Galeria Arsenał, ul. A. Mickiewicza 2, Białystok

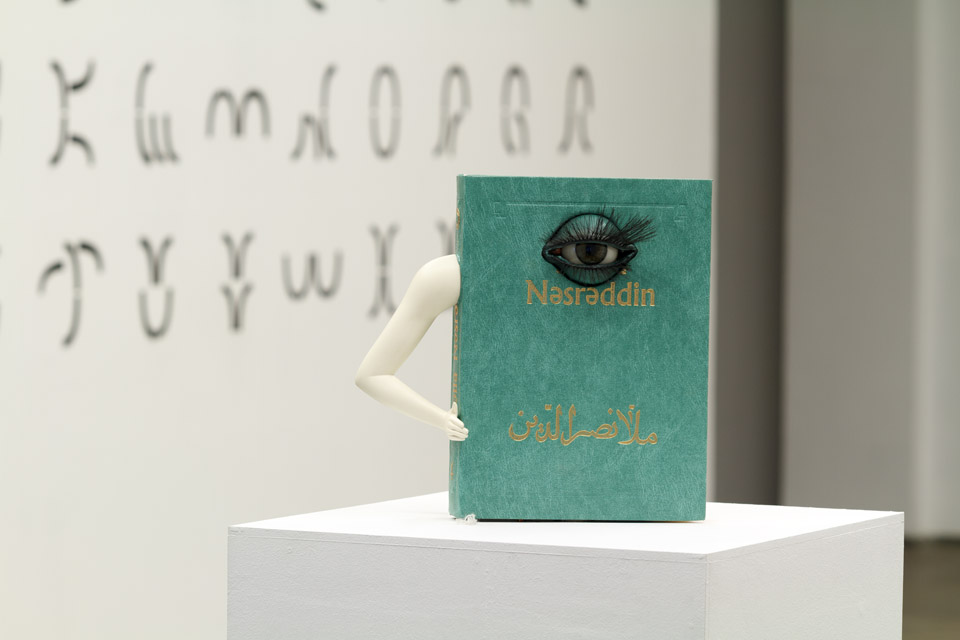

The point of departure for the Pure Tongue exhibition is Ludwik Zamenhof’s thought and his concept of a neutral platform of communication which would lead to cultural and ethnic divisions being overcome. His experience first from multilingual Białystok, then from multicultural Warsaw and, most of all, the situation of the Jewish diaspora motivated him to develop new social ideas whose final result was a universal international language. The first idea Zamenhof formed was Hillelism, involving reduction of social and mental differences between Jews and other European societies. Zamenhof believed that it took a universal language for the Jewish nation to peacefully coexist with others. As he worked on, Zamenhof’s premises became more general, now relating to all people, and the modified concept was termed Homaranismo. Agnieszka Jagodzińska wrote: “Zamenhof went down the road from Jewish particularism to all-encompassing universalism”[1]. Even though Zamenhof is best known as the originator of Esperanto, his ideas reached far beyond the linguistic field, including social, political and religious matters. First and foremost, Zamenhof was the precursor of multiculturalism and he wanted Esperanto to be not only a tool of communication but also a platform facilitating better understanding among nations and, as a consequence, effecting changes in social relations.

The main idea behind numerous attempts at developing a universal (perfect) language was to create a unification tool. The search for a perfect language encouraged a desire to return to a primal (pure) language. This was also the intention of Ludwik Zamenhof – to develop a “pure tongue” (Heb. safa berura) that would create harmony between nations. Walter Benjamin intuitively steered his reflections on translation towards the search for a perfect tongue. In his essay “The Task of the Translator”, he wrote: “Rather, all suprahistorical kinship of languages rests in the intention underlying each language as a whole – an intention, however, which no single language can attain by itself but which is realized only by the totality of their intentions supplementing each other: pure language.”[2]

One of the main themes of the Pure Tongue exhibition is the myth of the Tower of Babel. The confusion of languages (L. confusio linguarum) that is found in it is regarded as punishment. Therefore, an important point of reference within the context of this exhibition is the reversal of the significance of the myth discussed by Umberto Eco in his book entitled The Search for the Perfect Language. Eco cites theories suggesting that confusion – synonymous with multiplication or diversity – may be interpreted as a positive phenomenon, whose effects can be, for instance, observed in the development of ethnic bonds and territorial status. This view casts a new light on a wide range of questions pertaining to the politics of language, such as, for instance, the national language versus minority languages, marginalization of minority languages, language as an expression of ethnic identity, determination of one universal language in view of multiculturalism and multiethnicity. These problems seem most topical in an era of European integration. The European Union has decided that official languages of the community are the languages of all the member states. This was done to avoid conflict which would surely arise from introducing an official language that would at once be the language of one of the members (possibly English). It seems likely, however, that further expansion of the UE – and the resulting increase in the number of official languages of the community, will force the Union to choose one international auxiliary language.

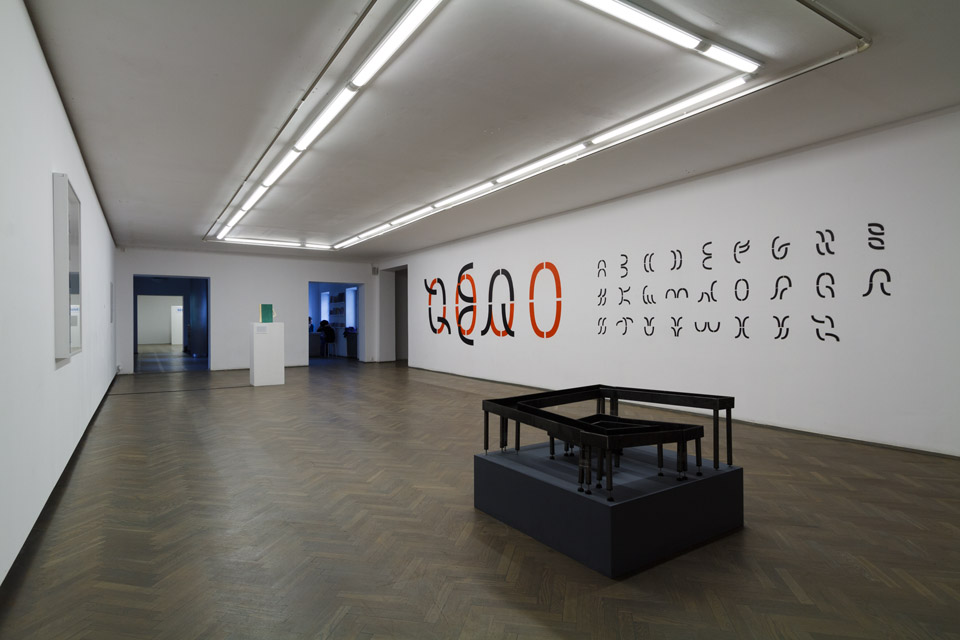

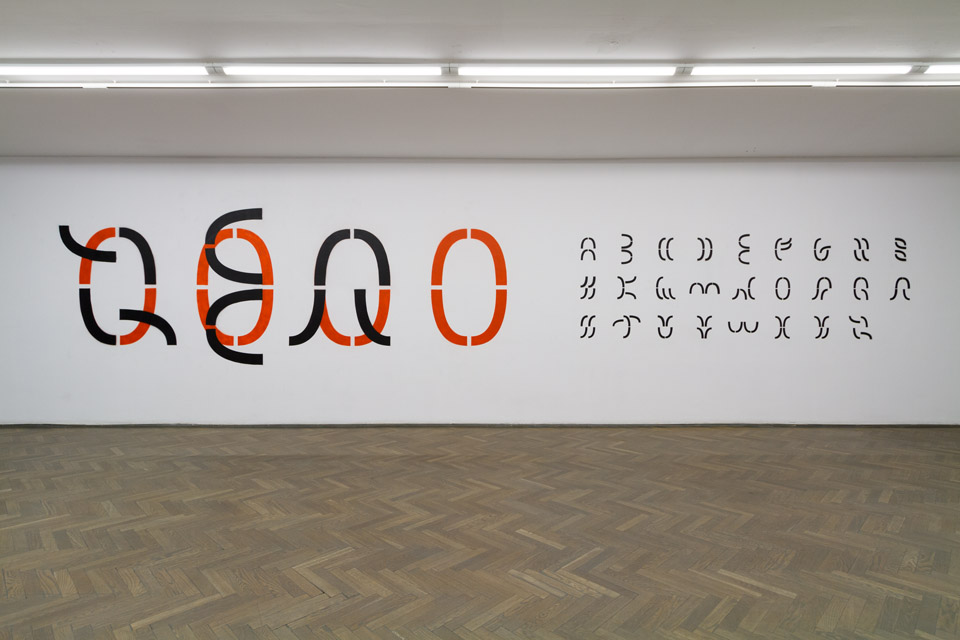

The question of an artificial language is also related to the politics of language; developing new languages or eliminating them is also part of this politics. Naturally, politics can transform language to serve its purposes. It is enough to remember totalitarian systems, including e.g. Fascism or Stalinism, whose interference in language was very forceful. Language has always been with those in power. Also, the choice of alphabet, the visual recording of language, was a political and cultural decision, e.g. the choice of the Latin alphabet suggested belonging to a specific cultural region. This led to several linguistic revolutions, as, for instance, Latinization of the Ottoman Turkish language implemented by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey in 1928 or failed attempts to Cyrillicize Polish language in Polish territories under Russian rule in the middle of the 19th century.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that human thought is determined by language and, as a result, it is language that conditions our perception of the world and state of mind. The thesis that “thinking and language is the same” means that language – to some extent – contains an image of the world. In the light of this concept, changes occurring in language as a consequence of globalization and communication networks (blogs, social services, internet communicators, mobile applications, etc) and related iconography (e.g. emoticons) seem very inspiring. The dominant language here is English – in the state of constant revolution, adopting it to never-ending changes in the grammar of electronic communication.

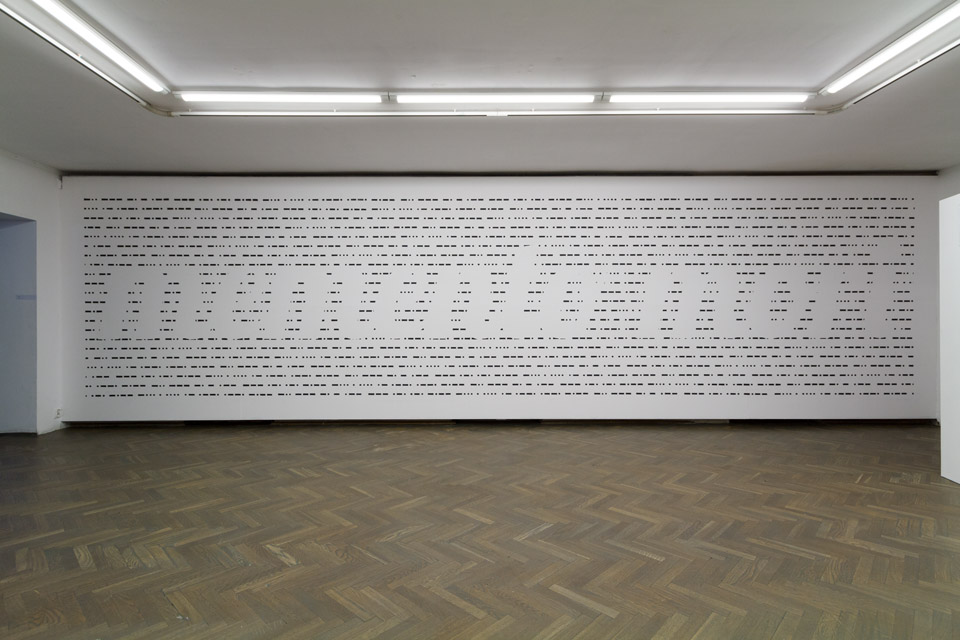

To sum up, the Pure Tongue exhibition centers on the question of universal communication; it explores the reasons for the desire to achieve it, the motivations behind creating artificial tools of communication in its various forms, including language, alphabet, lettering, or codes, e.g. the Morse code. Inspired by Ludwik Zamenhof’s ideas, it analyses his concepts within the context of current phenomena, both linguistic as well as political or national ones.

Agata Chinowska

translated from Polish by Monika Ujma

[1] Agnieszka Jagodzińska, Ludwik Zamenhof wobec kwestii żydowskiej, Kraków – Budapeszt 2012.

[2]Walter Benjamin, „The Task of the Translator” [first printed as introduction to a Baudelaire translation, 1923], in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn; ed. & intro. Hannah Arendt (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich 1968), pp. 69-82.

Related events:

20 June (Saturday), 11.00

– a guided tour of the exhibition with an exhibition curator and artists;

20 June (Saturday), 11.00 – 12.30

– family workshop “Everything can be a code”; carried out by Anna Koźbiel from Ad manum (recruitment);

25 June (Thursday), 18:00

– a lecture by prof. Walter Żelazny from the series “Is Art Necessary and Why?”

Galeria Arsenał, ul. A. Mickiewicza 2

Galeria Arsenał, ul. A. Mickiewicza 2

Entry to the exhibition is free.

Co-financed by the Minister of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland

Exhibition partner – Hungarian Cultural Institute in Warsaw

Media patron:

Ad manum (Anna Koźbiel / Adam Walas)

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30