Sputnik Photos. Lost Territories: The New End

The Lost Territories Archive holds several thousand photographs taken between 2008 and 2016 in former Soviet republics by Sputnik Photos, a group of photographers working together: Andrej Balco, Jan Brykczyński, Andrei Liankevich, Michał Łuczak, Rafał Milach, Adam Pańczuk and Agnieszka Rayss. Photographs contained in the archive are signed collectively and the set acts as a conceptual ‘assembly model’, presented in various configurations during exhibitions, lectures or in books. The latest archive-based publications include an illustrated lexicon titled Lost Territories: Wordbook (2016) and a photo book called Fruit Garden (2017).

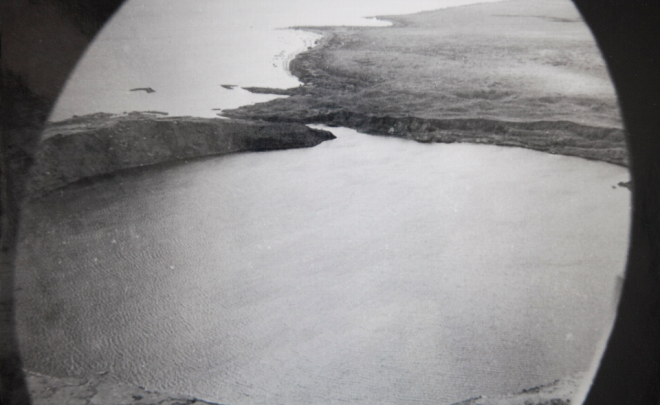

Extensive photographic archives, and Sputnik Photos are one of them, permit almost any kind of statement – they are easily reconfigured, reshuffled, and their meanings are adaptable. The photos selected for the New End show staged by the Arsenal Gallery have provided a basis for a narrative with an explicitly cautious, eco-political tone. The adopted futurological perspective presupposes geological time (applying to rock formation processes) and, consequently, rejects the concept of time that is measured with individual human lives. This exercise in imagination – viewing a photographic archive what it could be like in the future, in several hundred or even thousand years – turns the collection into a prophecy; it can be looked at through the prism of a slowly approaching catastrophe that will sooner or later hit the human race exploiting natural resources, damaging the environment and exterminating more and more species (including itself). This is a set of hypothetical ‘postcards’ sent to us from the era that will come after the Anthropocene, or the geological period characterized by massive expansion of Homo sapiens.

From the collection of several thousand photographs held in the Sputnik Photos archive a selection of slightly over one hundred has been put on display. They have been grouped thematically into three areas. The first is landscape modified by industrial, mining or military actions of humans. These pieces seem consistent with the tradition of landscape photography; in formal terms they are also closely akin to documentation of classic earthworks from the 1970s (both cases involve macro-intrusions into the landscape) or the scientific collection of the American Center for Land Use Interpretation. The second group (a slide show) focuses on the romantic and apocalyptic motif of ruins: traces of human activity take the form of abandoned architecture exposed to the workings of entropy, building materials, fences, bridges, electric tractions, allotments, road infrastructure, etc. The final area is dedicated to object (prosthesis, model, toy, teaching aid, prop), seen as ‘evidence’ remaining of human actions that will possibly prove more or less incomprehensible in the future such as, for instance, surgical operations, dance, teacher training, sculpture and so on. Amongst others, this category features a set of photos related to research in radioactivity and nuclear tests carried out in Kazakhstan. Another picture – an educational model of a chess school by the Heydar Aliyev Center in Khirdalan, Azerbaijan – can be seen in the building of the University of Bialystok.

The last photograph, a sort of endnote attached to the exhibition (or erratum, bearing in mind that the human figure is almost entirely absent from the narrative of the show), taken in a refugee centre in South Ossetia in 2013, is to be found outside the gallery, on a billboard. It offers a commentary on the racist and nationalist incidents occurring in Białystok’s public space which is becoming increasingly ‘Brown Shirt’.

The eponymous ‘new end’ yields some clues as to possible interpretations of the set of photographs from the Sputnik Photos archive. It foretells an apocalypse – but this apocalypse is neither absolute nor complete: merely a B catastrophe. It is with hope that we tend to speak of a new beginning, but a ‘new end’ sounds ridiculous; it is a state of suspension, an eternally open phenomenon. Will the end of the world as we know it be at all perceived from the perspective of an outlying district in Vitebsk or the Semey Oncology Center in Kazakhstan? Is the previous end something we have already been through? How many ends have there been so far? It comes as no surprise that the photographs from the Sputnik Photos archive, taken exclusively in the former republics of the Soviet Union, stir political imagination – especially nowadays when the demons of the Cold War awake and ‘facts’ are generated by internet trolls, fantasizing about the reconstruction of the Soviet empire. Not that long ago we said our goodbyes to history and celebrated its end. Let us greet it once more: shivering in anticipation of a new end, let us contemplate the ruins of old orders.

Sebastian Cichocki

translated from Polish by Monika Ujma

Cooperation from the gallery: Sylwia Narewska

Andrej Balco, Jan Brykczyński, Andrei Liankevich, Michał Łuczak, Rafał Milach, Agnieszka Rayss, Adam Pańczuk

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30