Robert Maciejuk

Sebastian Cichocki

Why teddy bears are sometimes sad, as well as other questions about the nature of things.

On the art of Robert Maciejuk.

Nothing is more this than that

Pyrron of Elis[1]

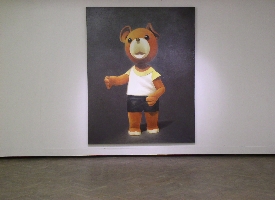

A bear, a teddy, a mutant, a wind-up toy, a furry humanoid. It’s really hard to tell who (or what) were the characters of children’s animated cartoons from the past. Those beings inhabited most curious places – crammed with odd furniture, thick with simulated atmospheric phenomena, artificial materials that imitated water or fire, and impudent teaching. Small, modestly furnished houses which the TV teddies populated, strongly resembled the image of Poland from the past two decades. Those creatures oppressed children’s imagination, mutating and evolving. Awaking not easily suppressed worry and raising hundreds of questions. Why did the teddies live alone? Where were their parents? How old they were, what did they do when the cartoon ended? Where were the borders of their artificial world?

Robert Maciejuk has taken up those issues in a series of paintings from recent years. He extracted the characters of TV fairy tales from their “natural” fairy tale environment. They seem static, as if posing for some sentimental, archive photographs. The pitiful snout of Nordynka, the corpse-like, thoughtless eyeballs of Koralgol, the absentminded face of Uszatek, and the grotesque, chubby body of Winnie the Pooh. It would seem that the TV creatures follow us with their eyes, the motionless buttons however, are no more than gaping holes.

Nothing can be more real than it seems[2].

Nature can be forged with no holds barred, alien elements may be added, and human desire for improving the world can be fulfilled. From fruit flies equipped with an additional pair of eyes, to glowing mice and mutant-guinea pigs, to transgenic super-cows. If nature seems dangerous or hard to control, we employ a set of proved techniques and methods that bring it down to yet another element of the well-oiled civilization entertainment machine. We got used to perceiving nature in terms of a smoothly working theme park. Nowadays it’s hard to avoid the taxonomic trap set by Carl Linnaeus in his “Systema Naturae”. Now, that every single element of nature has its name and surname, we believe that a life-form which is indescribable, simply does not exist. Nothing is arranged more neatly than earth and its inhabitants.

Let us turn our attention to an intriguing detail – since the very beginning of zoology many animal species have been discovered and examined on the basis of dead specimens – the ones that were hunted, measured up and stuffed with sawdust by hyperactive explorers. Large amount of discoveries is made in the archive halls of zoology institutes (in the vast collection of London Natural History Museum, scientists encounter new, uncatalogued, life forms every couple of days). What was once labeled as species turns out to be a separate genus, a larva turns out to be an adult etc. It’s elementary mathematics: number of extremities, eye-width, lack of a fin, degree of limb decline, brain weight. Everything can affect the genus and species name that endorses organism’s existence.

In addition to the fact that the number of examined animals is growing steadily (one can never know, if we are actually faster in discovering new species, or getting rid of those once systematized and preserved in formalin) we cannot resist the temptation to “design” new beings. And so we have zoology for the sake of consumerism and for children to hug. Zoology that satisfies scientific fantasies, and one that is used for intimidating. Plush animals, battery-operated dinosaurs, monkeys with diodes in their brains, Japanese robot-dogs, paper dragons, and Chinese koja carps. It’s good if they resemble man in some way – for instance, they can introduce themselves politely or perform an amusing trick. Proportions are of considerable importance here – a creature with huge eyes and a large (as compared to torso) head, stands a greater chance of someone bending over them with affection and tenderness. Hence, so young creatures “force” us to take care of them. We like faint beings with big eyes. There is a fair reason for hentai – porn manga – being a successful branch of animated movies industry.

Real brown bear weights three hundred kilograms, has small eyes, giant claws and short ears. The teddy bears in animated cartoons (and there’s a general rule on this), walks on two feet, has a soft, artificial fur and is capable of showing some kind of rudimentary mimicry. Robert Maciejuk tempts the viewer, by giving him soft corpses to hug. This land of veiled allusions and journeys towards children’s illusions however, is filled with treacherous traps. The painter plays a well thought out game with meaning and emotions, slowly and effectively, he removes the interpretative ground from beneath viewer’s feet. As no one hugs paintings. Paintings are assessed, by looking at them from a safe distance. Nothing exposes this artificial world better than a long and investigative gaze of the viewer.

Tamed animals, dressed in uniforms of fairy tale characters are sometimes clever, cunning, faithful, disloyal, vengeful, loving, and geeky. In general, every human trait has its equivalent in the collection of animal characters. Creatures from animated cartoons, on which Maciejuk draws, don’t act naturally. It is rather a bitter and psychedelic reflection on the factual social relations, rather than nature documentaries about the real life of the forest. This is because the TV bears, whose innocent snouts attack peoples’ minds with hundreds of associations, act according to human code of behavior. Some kind of companionship, tenderness and devotion links us with humanlike teddies. We feel closer to them than grasshoppers or deep water fish. More symmetrical physiognomy, four paws and a pleasant fur. It’s easier for us to imagine the teddies engaged, like humans, in numerous and trivial household activities, such as teeth brushing, listening to noise from an old radio or leaning back in a rocking chair. We would imagine, that once the cartoon ended with credits, the teddy bears, prostrate – free from educative obligations towards the Polish People’s Republic – could indulge in idleness and interesting conversations that lacked comforting punch-lines. The lights would go out and the cardboard houses seemed strangely distant and unfamiliar…

It may be a twisted line of thinking, but the expressive pirouettes and sweet face of Nordynka, the teddies evanescently submerged in water, or the inscriptions, as if quoted from old Coca-Cola advertisements (the Sixties were drowned in sensually-consumerist ambiguity). All of those are filled with some sinister sexual allusion. And the wicked, slick shapes of trees, tunnels, and smooth snowcaps in the woods. There is something ambiguous in the sight of a children’s toy in the hands of an adult. One thing is certain: we don’t handle the toy with care, we mess it up and, instead of hugging, tear its rotten guts out. It isn’t touching, but reminds one of the inevitability of events and the destructive powers of biology. This is why watchwords from pseudo-chocolate boxes and pictures of cartoon characters, stuck with plasticine, raise clouds of sentimental dust, as you can choke on memories that keep coming back like a hiccup. The amount of those elements (scavenged from old boxes, trunks, and cubes of picture tubes – familiar, mundane, dusted, boring, amusing, well droned on, untidy, sentimental, and unwanted) has to be limited.

Recently Robert Maciejuk went a step further – he removed the old cartoon characters from his works. He focused on items that were always behind the back of Uszatek, Koralgol and the rest of their friends. He became a landscape painter. The landscapes he captures however, are most curious. There is something airless and stifling in them. Some kind of fixation, a suspense; a focus on the objects, duplicated ad nauseam – yet somehow dangerous and unfathomable. The dummy-world would come back in childhood nightmares – water made of foil, that could never quench thirst, strange door drawn on a wall, that could not be opened, and fire, sketched in red crayon. Shadow cast by the dummy-mountains reveals their dwarfish nature. Artificial forests resemble a neat garden of bonsai trees on a window board. A nastily limited potential.

Nothing can be more real.

Nowadays it is widely known, that the world can be furnished according to our will. Nature can be a mobile and easy in use “do-it-yourself” set. Author of a classical album on animals from the Seventies entitled “Mammals – animals of the world ” marks on one page: “The abundant illustrations have been selected in such a way that, w h e n e v e r it was possible, they show the animal in its natural environment”. Young brown bear was shown in an environment utterly natural for the modern viewer – that is, in a zoo: climbing an artificial branch, in the middle of a concrete isle surrounded by a deep moat. In addition, the inadequacy of situation was stressed by a substantial description of habits and behavior of brown bear in wild. If Robert Maciejuk had been interested in the artificial world of zoological gardens, he would probably merely paint this concrete “playground” for animals. For the time being, his paintings are submerged in the sweet and sour psychodelia of landscapes. Small houses of TV teddy bears – with a garden, a compatible lake and a row of trees – seemed to have anticipated the possibilities of the architecture of nature. Like an American dream of paradise in the suburbs. “Nothing could be finer” reads the cheerful slogan in one of Maciejuk’s paintings.

In this context, a thought about the changes that took place in European museums and galleries at the end of 19th century becomes somewhat amusing. When the way of presenting collections (oriented towards a well educated viewer, capable of making his way among chaotically placed objects) ceased to suffice, new ideas for getting in touch with laymen, interested in science and art, appeared. Amongst many others, a peculiar way of presenting collections was put forward – the diorama[3]. Suitable objects were placed in their “natural environment”. For obvious reasons, such form of exhibiting quickly gained popularity in natural museums. Stuffed animals stood against the backdrop of dried plants, rocks and roots, and in the very back, a proper landscape was painted. Still performance tempted the viewer, the exotic was at hand. But like in Maciejuk’s paintings, the “landscape” consisted of curious details that would rather evoke a feeling of strangeness than delight. Stuffed bears were slowly devoured by clothes moths and the berry bushes collected dust. Nothing can be more this than that. Unless the ‘that’ isn’t what it seems to be…

Sebastian Cichocki, sierpień 2004

[1] Greek philosopher (ca 365 – ca 275 b.c.), author of extreme skepticism; he claimed that objects are not cognizable, and sensual experience and judgments are neither true nor false.

[2] Excerpts from the article „Honey, where’s my poison?” were used in the text. Originally published in: Opcje bimonthly, issue 2 (49), 2003.

[3] Strategies of Display, Julia Noordegraaf, Rotterdam 2002

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30