Minimal Differences

Minimal Differences

by Denise Carvalho (curator)

“Difference is ‘mediated’ to the extent that it is subjected to the fourfold root of identity, opposition, analogy and resemblance.”

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 29.

As Giorgio Agamben has established, the problem of any singular State is that it defines itself through specific forms of identities, whether general and homogeneous or specific and heterogeneous, but always through some form of identity. The lack of identity is a threat to the State. “What the State cannot tolerate in any way, however, is that the singularities form a community without affirming an identity, that humans co-belong without any representable condition of belonging (even in the form of a simple presupposition)”. This idea can very well exemplify the former Eastern bloc in its co-belonging status of Central Europe. Their various identities are here leveled out by a timely centrality, that which replicates the emblematic centrality of a global economy.

“Central Europe,” the umbrella term favored among formerly “Eastern” European countries, is defined by membership, not geographical position. Although called ‘central’, Poland, Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia, et al, remain in the periphery of continental Europe, having within their borders great differences in regard to language, religion, ethnicity, economics, and politics. These differences become ironically ‘minimal’ in light of the new economic demands that enable their survival in the global economy. This catch-22 leaves Central Europeans with little choice but to reflect themselves as stereotypes of ‘otherness’, as virtual realities, an otherness within, like two parallel worlds living together, even though only one is real. Postcolonial societies over the centuries have chosen to inhabit the very stereotypes they hoped to overturn; only by “being” could they eventually subvert their own half-identities, somewhere between the colonizer and the colonized. “Minimal Differences” explores the two sides of this ironic self-definition: one, which has become ‘central’, therefore losing all the privileges of subversion, resistance and rebellion of its previous state of difference and otherness; and the other, still a memory of itself, a self-stereotype humoring itself as a parallel reality, a phantom-limb, itching and hurting, but no longer real.

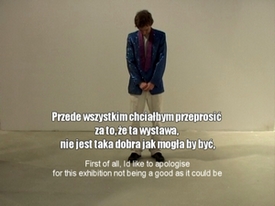

In Pawel Althamer’s video Teledysk (Videoclip), two generations of young Poles from the city of Poznań express their thoughts on growing up in Poland after 1989, revealing contradictions in regard to identity and social expectations. While a younger generation of teens claims “no ego, no identity,” enjoying a superficial nihilism typical of American Hollywood cinema, an older group of teens portrays a more conservative vision of their future, measured by hopes of managing and wishes of belonging. Their divided identity reveals social contradictions inherent in the conditions of centrality of a country that remains somewhat peripheral. Stereotypes are further explored in Katarzyna Kozyra’s video The Midget Gallery buys artworks, shown at Basel in 2007. The work focuses on a fictional dwarf gallery that attempts to buy artworks from famous galleries at an art fair. The concept of buying art—while simultaneously being art—points to how art has become equivalent to its market. The video also suggests a parallel between art as spectacle and art as commodity, but also references artists as laborers and the lack of local art investors in face of an increasingly richer international market. A fast-art market that sucks good and bad art stresses isolationist tendencies still present in central Europe, exposing a growing anxiety for contemporary artists, whose art is fated to be engulfed in a trendy and purely commercial market. The question is: what will happen to the meaningful art that was formulated in earlier decades, an art of critical importance, that is still in the process of being discovered?

In an article for “Flash Art” in 2009, the art critic and curator Jakub Banasiak made an analogy between the transitional period in Central Europe (1981–1989) and the economics of contemporary art, stating: “We are in an “in-between” period, a time when the new has not fully emerged yet and the old still remains alive,” exemplified by a growth of contemporary art through the investment of new art venues in Poland (e.g. The Centre of Contemporary Art “Znaki czasu” in Toruń, WRO Art Center in Wrocław and the new space of the Muzeum Sztuki (Museum of Art) in Łódź called “ms2” in 2008, and the Museum of Modern Art (Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej) in Warsaw to be opened in 2015. In contrast, the Polish public (state budget-financed) artistic institutions must subside on “salaries ten or more times lower than in the West, excessive red tape, inertia, an archaic management model and financial dependence on local political structures.” He adds that despite the vast changes, “a work culture and customs rooted in the former system remain alive and well in Polish public institutions” in which “curatorial clichés reign supreme.” After artists have succeeded and settled in the art world, “the structures of Polish art are only participating in their success, not having any by themselves.” Banasiak stresses that new global contexts in contemporary art are a given to young artists that have the option of making and marketing their work globally, in stark contrast to emerging artists from the 1960s and ‘70s, who had to gradually transform the market locally.

MORE

_______________________________________________

Geography of Identity, Geography of Art

by Izabela Kopania

– Is art important and why?

– It is necessary as long as it aims at promoting the idea of good instead of creating controversies.

This short exchange between Vesna Bukovec, a member of Slovenia’s younger generation artists, and an anonymous respondent replying to a questionnaire prepared by the artist was illustrated with Zbigniew Libera’s work Final Liberation 2. The 22-year-old woman’s response to the artist’s question, however, was in no way evoked in response to Libera’s photograph. Final Liberation 2 was added by Bukovec later as a form of authorial commentary. It would be hard to find a statement that more literally questions the reasoning behind the creation and existence of Libera’s work than this response. After all, Final Liberation is not only a commentary on the use of information as a mean of manipulation and on apriori acceptance of the images of reality provided by the media, but it is also a negation of the Platonic triad, which continues to guide the public’s assessment of art works.

Zbigniew Libera and Vesna Bukovec share little in common. They are not products of the same generation, they express themselves on different issues, using different media, and they have different artistic credos. The one thing they do share is their origins – their geographic (and therefore political, economic, and cultural) affiliation: both represent countries that are part of a greater whole known as Central Europe. This context infuses the issues they address with new meanings.

Central Europe – Central Part of Europe

A fundamental question that arises in every discussion about Central Europe is whether the region designated by this term actually exists. After all, we encounter problems just trying to map out the exact geographic borders of its territory, not to mention its cultural, ethnic, and linguistic boundaries, which are autonomous of any geo-political divisions.

The glue that held Central Europe together before the First World War was the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a federal state that existed from 1867 to 1918. During the 20th century, the territories and nations within it experienced three fundamental historical watersheds which resulted in political, social, and economic changes that are reflected in the way Central Europe is understood. The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles that ended the First World War gave rise to the formation of smaller nations (or, as in the case of Poland, to their achieving independence) that not only lacked cultural unity, but also displayed nationalistic tendencies. A second treaty, this one signed in Yalta, determined the shape that Europe’s political order would take after the defeat of the Germans in the Second World War. It sanctioned – with the consent of the Western powers – the annexation of the majority of “young” European states to the eastern bloc, dominated by Moscow. After 1945, the concept of Central Europe essentially ceased to exist. For more than half a century, it was absent from political discourse due to a clear division on the Old Continent between East and West, with the Iron Curtain as a boundary dividing these two completely different regions.

Central Europe – Selected Narratives

The authors of Breakthrough. Perspectives on Art from the 10 new EU member states (The Hague 2004) write in the exhibition catalogue that “Central Europe is slowly returning to the pre-World War I understanding of the region.” That this concept and the area to which it refers is returning to its prewar means of functioning signals no less than its slowly ridding itself of the stigma attached to it by the Yalta Conference: an inextricable – symbolic and factual – link with the East, identified then with the Soviet Union. The Soviet occupation – an imposed union between Moscow and its satellites where the relations were those between a hegemonic power and those it had colonized – shaped the image of the countries of Central Europe as economically and culturally backwards, cut off from the civilized world by an impenetrable wall.

The idea of Central Europe was revived in the 1980s, in particular, among the dissident literati of the eastern bloc nations. In his famous essay The Tragedy of Central Europe, Milan Kundera points to the region’s deep roots in Roman civilization and its role in the achievements of Western culture, from the birth of Christianity to the era of Cubism and Expressionism. For this reason, as the writer notes, the Soviet annexation was not only a political drama for the inhabitants of Central Europe, but also a shock resulting from its incorporation into a foreign cultural sphere. Kundera’s essay – like the expressions of thought written in the same spirit by the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz and the Serbian writer Danilo Kiš – contains a mythologizing element, constructed an image of Central Europe as a mental territory, a realm of ideas and melancholy decidedly distinct from the Soviet East.

MORE

Curator: Denise Carvalho (USA),Monika Szewczyk (Poland)Paweł Althamer

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30