MARTA DESKUR – Concise stories

It’s foggy and you enjoy peace and quiet[i]

Interview with Marta Deskur

First there is an emptiness, then the depths of emptiness followed by the depths of blue.

Yves Klein

Anyway, it’s always other people that die

Epitaph engraved on Marcel Duchamp’s gravestone in Rouen

Małgorzata Grygielewicz: The main theme of your installation “Concise Stories” (Opowieści Zwięzłe), which was on exhibition in February 2007 in the Białystok Arsenal Gallery, is death and time understood as the frames of human existence. Eschatological themes have accompanied art from time immemorial. What led you to create this work?

Marta Deskur: Many different “encounters” and observations have directed me towards “stories” about life, seen not through the prism of what we know, but through mystery- an inseparable part of life. “Human nature is made of the known and the unknown. We are made of both these things. We need both of them”[ii]. (Bill Viola)

How does this work fit into your artistic work as a whole?

I have recently read a comment by Łukasz Guzek, that after her exhibition in the Bunkier Sztuki in Kraków, Marta Deskur got down to something completely different. Indeed, I think I am an artist who prefers changes. In my work, I move through many plots, starting with pure abstraction – a form more spiritual for a person, moving towards realism – a material and physical form. I have analyzed the concept of family – woman, man, animal, community, identity, religion, etc. This was a solitary inner dialogue. The observation of the world, how we live, where we live, is a natural source and pretext for art. Artists draw inspiration from each other and that is why there is dialogue between them. “Concise Stories” is the continuation of a self-dialogue, the beginning of a certain type of “forum”- a blog written in partnership with others.

“Je me suis forcé à me contredire pour éviter de me conformer à mon propre goût”. (I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own taste). This is what the master, Marcel Duchamp, used to say. Do you subscribe to his words?

Yes, it’s all about art, its essence and existence. Further on, the same master comments: “On vit par son goût, on choisit son chapeau, on choisit son tableau”. (We live according to our tastes, we choose our hat, we choose our painting)[iii]. In my “Stories…”, I have chosen “my” quote, “my” painting, “my” artist, and carried out a dialogue with him.

What was Michel Houellebecq’s role in this work?

The paintings on display at the exhibition are the “reflection of a word” taken from a quote from Michel Houellebecq’s book entitled, “Atomized”: “The story of a man’s life can be as long or as short as one wishes it to be. A metaphysical or tragic option, limited, eventually, to the date of birth and death, traditionally written on a gravestone, has the natural advantage of being exceptionally concise”…

I refer to Houellebecq because I think that this writer aptly describes the mental state of a person from Western Europe. Considering Houellebecq’s cynicism, this observation was very much to the point. Going a bit further, I think that what is left behind us is not even the dates of birth and death but the pause between them.

The dates of births and deaths form only a framework. The most significant part is in the centre, it’s that hyphen, the line from-to.

The line has an interesting symbolism: it is infinite, straight, and has no beginning or end, but it “exists”. It’s a sure “road” within a certain time, within a distance, with loads of points and pinpoints.

We don’t know what was before us and what will be after us. The “line” turns into infinity and with time disappears, in either direction.

I would like to draw our attention to the exhibition’s geometry. Your paintings are enclosed in a square.

I have matched the line, the pause in between dates, with a square – in opposition to a circle, which was considered, by Indians among others, as the perfect form. Indian settlements were always arranged in circles, wigwams were circular and Indians were even said to move along the line of a circle, claiming that we, the people of Western civilizations, were enclosed in a sharp square that obstructed the free flow of energy.

You’re saying that the exhibition is metaphysical not because the topic of death itself is metaphysical, nor are the works themselves metaphysical, because they are not. The works are abstract (paintings), satirical, fantasy (light boxes) and realistic (video).

One of the elements of the exhibition is a séance performed to invoke the spirit of Yves Klein, who was the king of space, metaphysics and the void.

The paintings – light boxes are illustrations of visions related to death, related to the supernatural, to how material turns into spiritual – just like ceramic flowers and sepulchral pictures of the dead.

“Metaphysics is essential, because it’s an attempt to search for what a human being is, a preparation for receiving the mystery”[iv], that’s what my grandfather, Stefan Świeżawski, thought. He also wrote that metaphysics was inseparable from philosophy, and philosophy from human beings. Following his train of thought, entering the field of art, one can consider that if “art is everything that is done by hand and mainly by a person” (“l’art, c’est tout ce qui est fait avec la main, et generalement par un individu” – M. Duchamp[v]), this means that art is inseparable from humans and thus inseparable from metaphysics.

The theme of death, the so called vanitas, in modern iconography filled the emptiness after death. How does contemporary iconography relate to this principle?

Contemporary iconography related to the theme of death is, in a certain way, a reflection of the void, where nothing is something it shouldn’t be.

Emptiness “in itself” is neither positive nor negative, it’s an entirety containing nothing. In contemporary Christian iconography, we deal with its negative reflection, which we can also refer to as kitsch. When we look at the pictures of saints, Virgin Maries, Christs, we realize that they have nothing in common with holiness, but are the effect of its commercialization.

At present we deal with neither religious painting, nor any other religious masterpiece. What’s left is only a kitschy reproduction. Jean Baudrillard would say kitschy devotional articles are yet another creation of a consumerist society …

Marie-José Mondzain, a French philosopher and painting historian addresses this issue perfectly. In her book, “Image, icône, économie : Les Sources byzantines de l’imaginaires contemporain” the author shows a breakthrough in art, namely Christ’s Resurrection, who became an icon in the likeness of God. Based on the etymological analysis of the words “icon” and “economy”, the author notes their inseparability.

We can take things further and claim that it was the great works of the masters of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, related to religion that hindered our imagination of holiness, by presenting God as a figure. And this was caused by the economy and the aforementioned tastes, that is, work commissioned through patronage. The economy drove the “icon” and still does – both in art and in religion – but contemporary art has strayed away from faith, for economic reasons, as well.

Coming back to emptiness, do you perceive it as a negative? As in photography: we have a negative and a positive?

Not entirely. The mere “presentation” of emptiness can be negative or positive. Klein managed to present emptiness in the depths of blue. This is what I call positive presentation. However, the reflection of emptiness in the eyes of some people is a sort of negative emptiness – thoughtless. The contemporary vanitas you refer to is a negative emptiness, literally, the vanity of vanities, all is vanity (Koh 1-2).

A negative and a positive in photography, as in sculpture, carry a wonderful relation between truth, a depth and dimension of their reflection, they make us aware of the relativism of concepts.

When we present emptiness, that is, something unknown, suspected of exceptional vastness and transcendence, literally, using the simplest means, such as the icon or subject personified, it stops making sense.

A positive is emptiness and a negative is its reflection, but mind you, a reflection can be either positive or negative.

The works: The Satyr (Satyr), The Assumption (W niebo wzięcie), The Ascension (W niebo wstąpienie),Transformation (Przeobrażenie),Damnation (Potępienie), On earth (Na ziemi), On a Trip (Na wycieczce) are all paintings that can be considered part of contemporary vanitas iconography. They are a negative reflection. They must be placed between reality and the illusion of reality. As J. Baudrillard wrote: “The real blends into the real, too real to be real – the false becoming too false to be false – this is the end of aesthetic illusion. […] Good shines through evil, falsity through truth, ugliness through beauty, male through female, each squints at the other. When falsity takes over the entire energy of truth or reverses its direction, that’s when art and illusion are created. When reality absorbs the entire energy of unreality that’s fiction”[1].

The image was a tool for popularizing religion. Biblia pauperum, which was based on image and not on the text, brought followers closer to hell, or actually to the image of hell. This led to the reformation and to the tearing down of paintings from the walls of temples.

Today, illustrative Bibles for children are handbooks for the “poor in spirit”, the worst possible nightmare. They could have perhaps provoked an exceptional imagination, which is of great value, but I do not think that they guided readers towards the fundamental paths of depth and theological reflection, which are essential to fully understand faith. This is because “the Word is the beginning of everything, and therefore the fundamental sphere of our life is cognition. Faith is the greatest grace a human being can receive…” – S. Świeżawski.

Fortunately, art doesn’t play the same role as it used to in the past. Times when the church subjugated art belong to the past. Some artists still make use of religious themes in their work. My paintings from “Concise Stories” are a heritage of this multi-century history of the church and of the simplified imagination of what is superhuman, timeless, mysterious. These paintings require no preparation, they naively respond to the needs of a simple viewer shaped by the church today, but these are not Bible illustrations.

It’s a cynical presentation of contemporary, “economic” spirituality.

From the point of view of Christian theology, every artistic act contains an element of heresy. Michelangelo or Caravaggio, when painting biblical scenes, entered into a dialogue with sacredness. Through digression and by searching for and putting their image of holiness to the test, they departed from faith, which in principle is not based on understanding but on believing. Every attempt to take a rational approach to faith, as in the case of the Fathers of the Church, as well as later theologians, came close to heresy. The same goes for art, which served the church as an educational and propaganda tool, and at the same time was completely liberated. Every type of creation is related to a type of criticism, and in the case of religion this is a sin.

Contemporary man is not only absorbed by religion, but also by politics and social life. Religion is an element of the reality they must criticize (“ex officio”). I think that heresy, both in religion as in art and science, is indispensable to cognition.

Let’s go back to metaphysical themes. The entire work, which consists of light boxes, paintings with flowers, and medallions, is a sort of a set design for a séance, which you conducted in the gallery on the eve of the opening. You have prepared a scenario according to which Yves Klein was supposed to show up at the Arsenał Gallery. How did you prepare for that? How does such a project fit into your life of an artist?

Working on a project about death, which is actually a project about life, the question, “what comes next?” emerged naturally. I used to invoke spirits in my childhood. Abilities that are in some form passed on from generation to generation, from grandmother to granddaughter, which I had previously practiced socially, and now I have made use of in art.

I have decided to make a similar attempt, but in a completely different scenery, namely in a gallery. The interference of a séance with the exhibition seemed essential to me since I wanted to invoke the spirit of Yves Klein, for whom one of the attributes of art was direct interference with space intended “for art”. I have prepared a text, a kind of scenario, especially for this occasion.

Text read during the séance: Spirit come! Do you wish to speak to us?

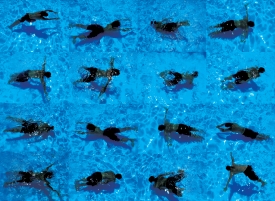

When Klein’s spirit appears: Before I ask you a few questions, I would like to emphasize that I liked your performance with women, who painted their beautiful bodies with blue and then stamped them on white. The body turned into a form, but did it become immaterial? At this moment, nowadays, one can say that these reflections are even more than immaterial, they are priceless, and thus very expensive, in fact- unavailable. At one point in the film registering this performance of yours, the camera shows the audience watching this extraordinary event. We can see very elegant and stiff Parisian women and stiff, young and old Parisian men. Their eyes gazed at the beautiful and naked bodies moving with great grace. The spectators’ eyes showed delight, admiration, embarrassment and a certain type of emptiness. They were being “attacked” by the material. Bodily matter. The matter of natural beauty- erotica. You were observing this, but did you feel the emptiness? (We are waiting for him to answer yes or no).

Next question: Why did you want to attain the state of emptiness during your lifetime? Do you consider death as a continuation?

More questions will arise live during the séance. Afterwards we will bid him farewell.

Why did you invoke Yves Klein?

I had just seen a very good exhibition of his at the Pompidou Centre and something inspired me there … (laughter)

I wanted to ask him whether, after death, he realized his desire, the desire of emptiness, in an absolute way. By trying to invoke him from this emptiness, by asking him a few questions, I wanted him to fill the space of the gallery with his immateriality, his spirit, so that the exhibition literally achieved a full dimension of unity of the spirit and the body – of course half jokingly, half seriously.

During the séance you played the role of a medium? To what degree was the call of the spirit an improvisation?

Often, what is demanded of artists is near absolute artistry, something they also expect of themselves. The simple position of an artist as a medium is a primary and inseparable element of the creative act. I would like to point out that by acting as an artist, I invite another artist to co-create the exhibition. The calling of the spirit of an artist was a peculiar dialogue with the contemporary status of artwork. I was searching for answers to questions about artwork and the artist. Whose work was it? And was there an author of this work?

If we approach this “spectacle” in, let’s say, a doubtful way and consider the moving plate as pure manipulation and the behavior of the participants – who are experiencing an “unnatural” state of mind – as a type of autosuggestion, then we quickly come to the conclusion that from the project’s point of view, it’s not important. Because we do not have clear-cut answers to all our suspicions … What’s most important is that Yves Klein came and talked about art.

What’s most important is the work. Was the artwork a fragment of the scenario I read as the director of the spectacle? Or was it an improvisation, that is, the moment when Yves Klein showed up and lead the spectacle? Or was the artwork the act itself of calling the spirit to the gallery or the documentary that remained after this event? Etc.

The artist is always a mediator until the work is created. I think that the artwork became a fragment the moment none of us knew what would happen next, even if it was our suggestion, our surrendering to the work that acted as the director. Here, the very moment of transition is very important, when none of us know what will happen next and whatever takes place does not consciously depend on us. Artwork is the moment when we consciously have no influence on what is happening. An artist can be the suggestion or autosuggestion, and most of all a film camera that registers the event.

Can you remember the questions answered by Yves Klein?

We asked him what his favorite color was and he replied that it was not blue, but white, which really amused us. After all, we were in Białystok (Białystok literally means “White mountain”). Then we asked him what it was like in the other world. How could he describe “timelessness”? Klein gave a very poetic reply: “It’s foggy and you enjoy peace and quiet”.

A dialogue between you and the invited artist, a dialogue between earthliness and eternity, a dialog between your work and somebody else’s work triggered a discussion on art, art understood outside of the context we are used to. One of the questions asked was “Can you be an artist after death?”

Questions that were inappropriate to Yves Klein’s reply, on the one hand, show a complete misunderstanding of the situation, and on the other hand, confirm its authenticity.

In principle, in these types of situations the result is jabber, sentences are meaningless, individual letters and numbers are read anxiously. All the participants hope to receive some sort of message. A mixing of themes and notions grows along with a general bewilderment. The human being is only the driving force behind a work of art. Is he an artist- we don’t know. The end of the work belongs to another author.

We have two impossibilities here: the first one is that we cannot talk about art, and the second one is that we cannot talk about art with a dead person. As an artist, you naturally conduct a dialogue with artists throughout the past centuries, drawing inspiration from their art. However, it is your own intimate dialogue. The encounter with Yves Klein and the conversation with him was not an intimate conversation. It was witnessed by others who automatically became a part of the work.

We became a part of the work and its fulfillment. To me, inviting a deceased artist to dialogue is a form of confrontation or even a way of squaring up with history. I would like to summon the spirit of an artist from the future if I knew his name, since I am interested in history in terms of its future, not the past.

Another theme was the desire to invoke the spirit of Marcel Duchamp in Klima Bocheńska’s Gallery in Warsaw. Did you want to invite him to a game of chess?

The spirit of Yves Klein appeared and readily replied to the questions posed. The situation was different with Marcel Duchamp’s spirit.

Marcel Duchamp was an amazing chess player, who often participated in chess tournaments. Our game began when I challenged him to a game, that is, the moment this idea was born. The game was played mentally, not materially. I perceived certain situations as signs to continue the game. I practiced a lot, played with a computer, analyzed the concept of chess from every possible angle. I read books on chess in order to be well prepared for the game, which was planned for the opening day of the exhibition at Klima Bocheńska’s Gallery in Warsaw.

A few days before the exhibition I received sad news, which prompted me to call off the exhibition. Since I was already mentally and physically involved in the game with Duchamp, I perceived this incident in a very symbolic way. A game of chess ends with the killing of the king. In this case, the king was Wojciech Bruszewski, an art collector and patron and the initiator and co-founder of this Gallery.

Wojciech Bruszewski was the king, and Marcel Duchamp played the game?

I wanted to conduct the chess game according to the same rules as the previous séance with Klein, which was also within the confines of a gallery. Wojtek’s death made this impossible. Death, which is not real in art, which you can only talk about and create on illusion of, became absolutely real. All the actions taken by me in my attempt to create an artwork, became real. I realized that I could no longer “play with fire”. Moreover, a few weeks before the opening I decided to name the exhibition at Klima’s gallery, Epitaph, referring to the quote on M. Duchamp’s gravestone.

I am convinced that these two things were not objectively related in any way, but for me, subjectively, it was a real shock.

What was the installation you put up in Klima Bocheńska’s Gallery about? I can recall a shadow theatre . There was a table with a chessboard and lined up chess pieces, and two empty chairs opposite each other; all this against the background of blue light.

I made reference to Marcel Duchamp’s work, actually a photograph from his retrospective exhibition in Pasadena Art Museum in California in 1963, in which Marcel Duchamp played a game of chess with a naked woman, a model Eva Babitz. It’s a kind of a readymade of the photograph.

I prepared an “immaterial” adaptation, where the idea itself became the material. The film recording the chess game, which actually does not exist, provides light for bringing out the objects.

Chess was a symbolic activity for Marcel Duchamp. A strategy that prevented failure became a form of art for him.

Why did you choose Duchamp?

Because I felt a desire to conduct a dialogue with the master, and besides there’s a very interesting concurrence between his name and the word “duch” (‘spirit’ in Polish). It was supposed to be a game of chess with Duch- Amp.

I have great respect for the absurd and surrealism, which are the most apt means of artistic expression in describing difficult issues of reality. Without humor, illusion and irony you can neither read the work “properly” nor create it. I chose Duchamp because his surrealism is constantly present in art.

If Duchamp hadn’t shown his urinal in a gallery, art would look entirely different.

Looking at the exhibition, one gets an impression of surfeit. There was also live music at the opening. While the music in the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok was pleasant, in Klima Bocheńska’s Gallery it was unlistenable.

Referring to the tradition of John Cage and Fluxus, I wanted my artwork to serve as a musical score. My aim was not to provide a musical interpretation of the works lying or hanging in the gallery. I think that every object can become a musical score. Classically, a musical score is a visual form, but a blind man can also create his own operation and recording code. A classical musical score is based on the mathematical system of the stave, every note corresponds to a specific musical value. When we leave out the mathematical aspect, we get an image, which is not precisely related to sound, and this is the type of music score I am interested in.

I wanted “Concise Stories” to be expressed not only visually but also musically.

Finally, I would like to ask you to interpret the painting “Transformation”, where we can see a dancer in a symmetrical arrangement of figures against a red background.

“Transformation” is a special painting that relates to my grandfather’s theory on death. My grandfather, who was a philosopher and theologian, claimed that a human being in his lifetime is like a caterpillar, which doesn’t even know that after death it transforms into a butterfly. Death, according to him, is a state of transformation similar to the change that takes place between a caterpillar and a butterfly. The transformation motif suggests metempsychosis, the transformation of the spirit into a different state. The process of death or transformation must be accompanied by some sort of time and “no-time”, the pain of existence or non-existence. Pain or bliss. And what next? “It’s foggy and you enjoy peace and quiet…”

[i] Statement of the spirit of Yves Klein during a séance at the Arsenał Gallery, Białystok, 2007

[ii] Ludzie nadal trochę boją się sztuki wideo. Paulina Reiter talks to Bill Viola, „Obieg”, 29.05.2007

[iii] G. Charbonnier, Entretiens avec M. Duchamp, André Dimanche éditeur, Marseille 1994

[iv] Stefan Świeżawski, Alfabet duchowy, published by Znak, Kraków 2004

[v] G. Charbonnier, op.cit.

[1] Jean Baudrillard, Przed końcem. Rozmawia Philippe Petit, pub. Sic!, Warszawa 2001

Curator: Monika SzewczykMarta Deskur

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30