Kateryna Lysovenko. Cemetery Garden

Kateryna Lysovenko. Cemetery Garden

Катерина Лисовенко. Цвинтарний сад

27.05–30.06.2022

Curator: Eliza Urwanowicz-Rojecka

Adults-only exhibition

Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok

Adama Mickiewicza 2, Białystok

The Cemetery Garden project is something akin to a war journal kept by Ukrainian artist Kateryna Lysovenko, forced to leave her hometowns of Kyiv and Odessa with her children in the wake of Russian aggression. The exhibition comprises the artist’s daily notes, including reproductions of works impossible to evacuate from her studio in Kyiv, as well as drawings and paintings created after the war had broken out, over a time of compulsory migration (during residencies offered to the artist by BWA [Art Exhibitions Bureau] Zielona Góra and in Graz). To quote Lysovenko herself:

I don’t want everything to be annihilated again, I refuse to accept oblivion of what has been annihilated, I want my country-garden in bloom again. This is not the first time they came to raze it to the ground. I refuse to forget. I am a mobile cemetery. Such is my way of preserving everything which has been obliterated in and around me.

A cemetery is a place of reminiscence. This is where new life is born, the shared cemetery garden comprising assorted memories. […]

In my cemetery garden I am thus engaging in a utopian act of resurrection, an act of disagreement with the repeated replication of nameless graves, violence and murder. I dissent. While a warless world is still impossible, I refuse to accept such state of affairs.

***

Kateryna Lysovenko

[1] In Kyiv (all footnotes by the editor).

[2] NAOMA – National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv.

[3] Boychukists – a group of Ukrainian monumentalists, students and followers of Mykhailo Boychuk (1882–1937), representatives of “red art” and “red culture” of the 1920s and 1950s.

[4] Wall of Remembrance – a bas-relief over 2,000 m² in area on the Baykov Cemetery site in Kyiv. Example of Soviet modernism and the largest work of Ukrainian monumental art. Created over the years 1968-1981. In 1982, authorities decided to pour it out with concrete. In 2018, as part of the Kyiv Art Week Festival, a part of the concrete layer was removed under Melnichenko’s guidance, to reveal a 6 m² section. Works were funded by the municipal budget.

Curatorial Text

I carry within me gardens of sadness, gardens of wrath

brought by unmitigated loss, I memorise everything

that disappears, I want to breathe more deeply to

make space for more, I am now a mobile cemetery.

Kateryna Lysovenko, March 8th 2022

War in Ukraine did not begin on February 24th 2022. It has been going on for eight years. The constant thought of its potential outbreak has been influential to the perspective of successive Ukrainian generations. Remembrance of World War II and the profound awareness of ancestral trauma and Russia’s imperialist intentions have become a permanent and deeply rooted presence in Ukrainian daily life, affecting everyday choices, activities and attitudes. This has been particularly visible in the oeuvre of such artists as Nikita Kadan, Antigonna and Kateryna Lysovenko. Their works have been harbingers of war as well… why have so few of us paid attention?

It was exactly the aforesaid awareness and remembrance that triggered a self-reflex in Kateryna Lysovenko once war had broken out. She instinctively knew what had to be done: pack the children’s things as soon as possible, leave the flat and studio, and set sail into the great unknown without abandoning her artist persona. She collected bare necessities, and two tubes of ink. She could not take her works (drawings and paintings, many of which large in format). While some were later successfully evacuated from Kyiv under Russian siege to the more tranquil town of Uzhhorod, others were left behind in the studio (including the book of sketches immediately preceding February 24th 2022).

Welcome to an encounter with the oeuvre of Kateryna Lysovenko, an extraordinary woman and artist. A person who – in the midst of war trauma and facing forced solo emigration with her children – had never forgotten that art is her vocation, and decided to use it as a medium in preserving the memory of savage images and texts depicting war in Ukraine. She made another decision: to be brave in naming the reasons for the invasion. As a single émigré mother taking care of her children, she filters her narrative through the events and experience of motherhood, sharing her most intimate and sensitive moments. Her works are gentle and gruelling, discursive and emotional in equal measure, all painfully genuine.

“While wartime events are ghastly and incomprehensible, the arrival of warfare as such can and should be analysed. I believe that interpreting this war as a random act of madness by a Russian leader is a major mistake. This war is a consequence of the evolvement of Russian statehood over the past three hundred years at least. Ukraine has had to struggle with the issue century after century. Each new war resembles – and yet differs from – the one that went before. Ukraine under Soviet rule was no colony in the regular sense of the word. Soviet Russia had developed a form of totalitarianism which altered the societies of all countries it had conquered,” reads the artist’s journal entry of March 4th 2022.

“Time for reflection will come. Today, we have been assigned witness roles,” said Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan who has remained in Kyiv, during the panel When Words Stick in the Throat. Activist and Artistic Reactions of the Art Community to the War and Political Protests (May 11th 2022).

Consequently, the exhibition has become something akin to a testimony, a subjective analysis of war. When commenting on brutal developments and referencing cruel reality, the artist is screaming on behalf of young Ukrainians, wrathful and attempting to transcend their victim character.

We are showing i.a. works created prior to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, successfully transferred to Poland from Uzhhorod: The Abduction of Europa (December 20th 2021) and Untitled (February 22nd 2022). They are the foundation for the exhibition’s narrative, pointing to i.a. Europe’s indolence in the face of war and threat to the continent, and to Ukraine’s wrath and empowerment, respectively.

Successive works created after February 24th 2022 are a commentary on the cruelty of wartime events, and narratives associated with war. Having been created in an ongoing process, artwork titles feature daily dates. Frequently preceded with annotations in the artist’s journal, they are accompanied with fragments of text in exhibition space itself – next to the works, or as printouts available to visitors.

We are also showing the artist’s original sketchbook she drew in after having left her hometowns of Kyiv and Odessa, and the aforementioned tubes of ink she managed to collect from her beloved Kyiv studio.

Reproductions of selected works which could not be evacuated from the studio in Kyiv will be featured in a publication now under development by the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok, with excerpts from the artist’s journal.

Eliza Urwanowicz-Rojecka, exhibition curator

Zuzanna Sękowska

A World Beneath Eyelids

Kateryna Lysovenko’s series of works on display at her solo exhibition Cemetery Garden at the “Arsenal” Gallery in Białystok provokes a reflection on the dual role of painting: an element of resistance – and something akin to a case designed to hold shards of memory. Remembrance and the “utopian act of resurrection”[1] seem to be of fundamental and symbolic importance to the artist’s creative philosophy. Memory becomes a safe space, affording survival to people, places and ideas seeking shelter from evil, destruction, oblivion.

This particular instance references the duple effort of memory. Shown at the exhibition as reproductions, some of the artist’s works could not be evacuated from the studio in Kyiv. Do they still exist today?

The exhibition’s most significant item is an artefact – the artist’s sketchbook she was drawing in in the wake of her reality-enforced exodus from Ukraine. Notably, its form matches Lysovenko’s paintings.

In her earlier works, the artist had referenced Ukrainian legends and flagship monuments of culture, blending historical tropes from Ukrainian lands and East Slavic motives with fantastic worlds of the Greek, Roman and Germanic worlds. Her drawings, paintings and frescoes depict goddesses, centaurs and syrens[2] (as well as effigies of Kyi, Shchek, Khoriv and Lybid’[3]); her works have been shown in the streets of Ukrainian cities on standards and banners.

In her most recent series presented at the “Arsenal” Gallery, the artist continues using her painting vernacular and repertoire of symbols she has developed to date, supplementing and expanding them to include new forms and content.

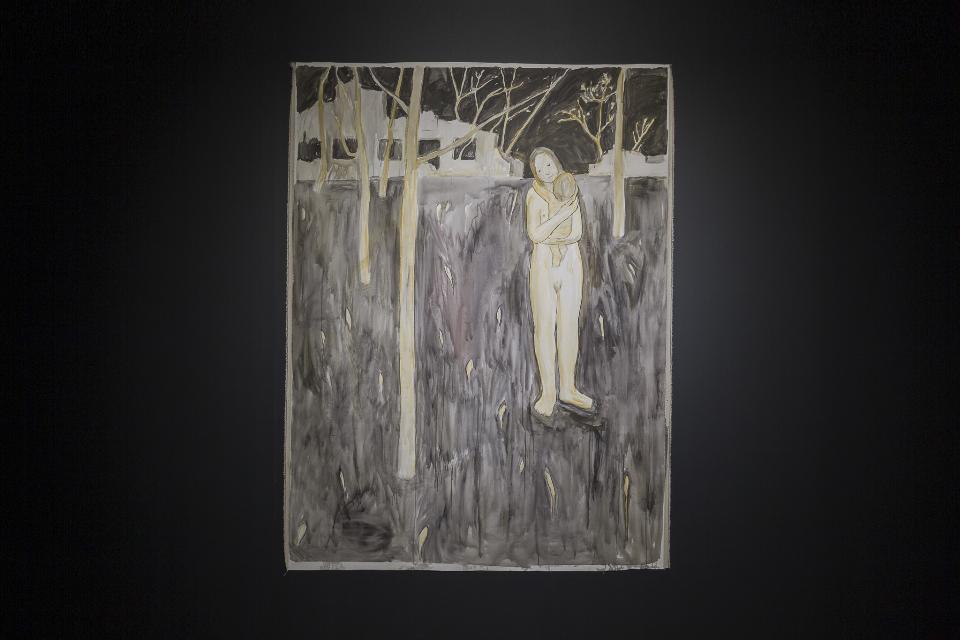

She is particularly fond of placing her protagonists in gardens, considering them symbolical. Her gardens of memory are populated with mythological creatures: fauns, centaury, pans. Lysovenko makes them trusting, kind and gentle. The artist also shows figures of children, mothers, women and girls in settings of trees and marshes.

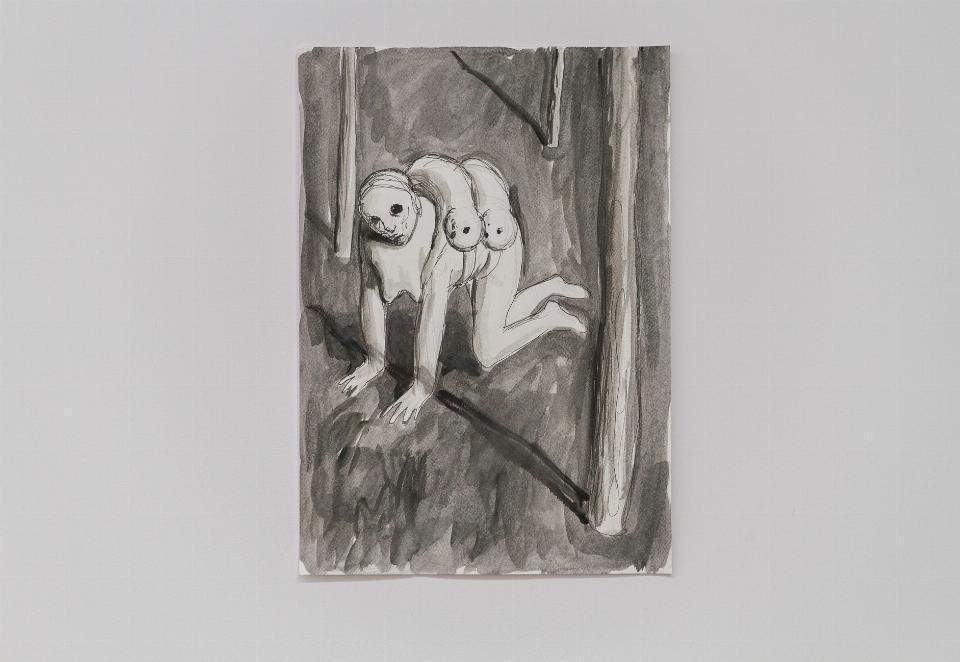

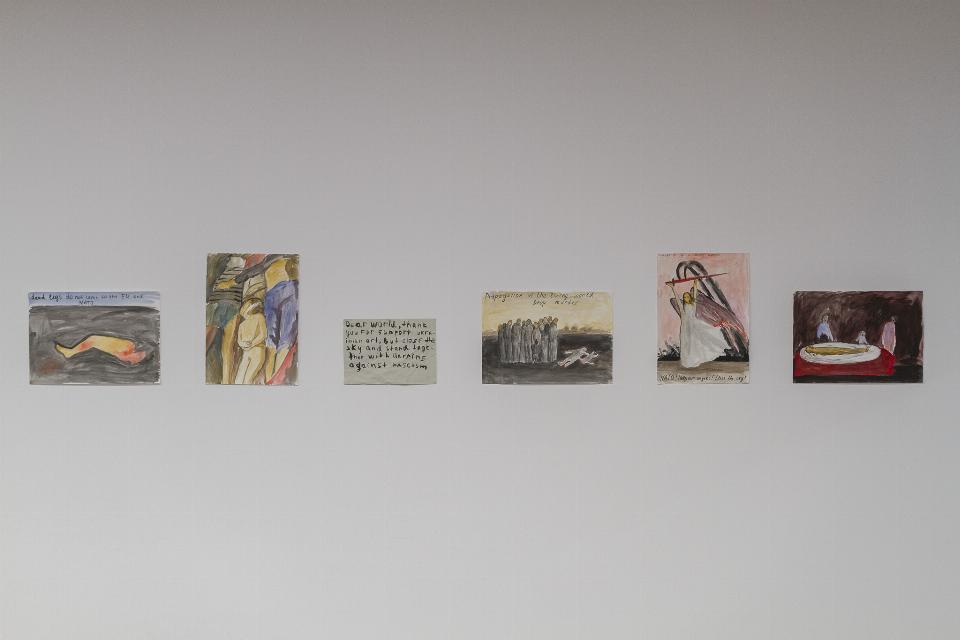

The group of works comprising the Cemetery Garden exhibition includes wartime tropes. Yet Lysovenko’s intent was not to focus on battle or soulless documentation. It is more of a poignant atlas of horrors, touched up with directness and irony. Sketches and paintings are brimming with writhing corpses, cowering civilians, helpless characters, infant skeletons, bodies raped and dismembered. Extracting them from realms of anonymity, the artist gives all of them a voice. In a series of colourful watercolour (or, more rarely, acrylic) drawings, she confronts the viewer with brutality and truth, drawing on the aesthetics and language of classic wartime caricature and satire (victims flipping the middle fingers at aggressors, imperialists, sick ideologies etc.).

Lysovenko creates poster graphic compositions, combining painting techniques with handwritten annotations. The slogan “NATO. Help our angels! Close the sky!” (the appeal to close the sky over Ukraine, repeated by the press and media) brings to mind Käthe Kollwitz’s 1924 anti-war poster „Nie wieder Krieg” (Never Again War).

The artist describes Ukraine’s historical deadlock, years of Great Terror followed by the Great Famine (Holodomor), the closed circles of consecutive wartime years (An Evening in Ukraine. 2022, 2014, the 1950s, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s), offering an ongoing commentary on the nightmare. Such works as a severed limb with an ironic caption “Dead legs do not come to EU and NATO”, a giant penis-shaped missile labelled „за детей” (for children) abandoned in the middle of a field, or the work Russian Hero Liberated Children, are all explicit illustrations of crimes Russian committed across Ukraine, and of the associated cynicism. Some of Lysovenko’s wartime sketches are brought together through the slogan “Propaganda of the living world”. The artist also references photographic frames which have become war symbols, reproducing media images of death and cruelty. A (child’s?) bullet-ridden body, medical staff leaning over it; mass graves; bleeding bodies of rape victims; scattered corpses.

The aforesaid collection of Lysovenko’s works forms part of the world art canon depicting times of war and massive global conflicts, anti-war manifestos and records of murder and cruelty, the author alluding to the canon consciously and deliberately. Emphasising issues of history repeating itself – and hopelessness of reducing human suffering – she thus points to their timelessness or agelessness (the iconography of suffering having been firmly rooted in the history of art and visual culture).

In Lysovenko’s works, tropes of wartime documentation and records of reality intertwine with a story of parallel worlds – wherein the forbidden meets the evil and the beautiful, the imagined and the unimaginable. Time and the present intermingle, spiralling into perdition. Just as evil and destruction had been possible before – in a world primaeval, bordering on the mythical – it has become possible today, here and now. Are centaurs rising from a pit dug in red earth thus standing on the edge of a mass grave?

However it may sound, there are wars persisting in mass memory – and then there are murders and genocides obliterated in world remembrance. As difficult as it may be to put down in writing, their gravity depends on the overall hierarchy of meanings. In her works, Lysovenko combines sketched painting documentation and historical documents with images overflowing with symbolism and secrecy, realism and magic, causing disturbance to hierarchising options and evaluating potential in consequence.

Lysovenko’s extraordinary creative force lies in her incredibly refined practice. Her painting displays excellent technique and formal background – she has mastered drawing, and is skilful in her use of colour and mood. Efficient practice has allowed her to freely switch between dimensions and techniques – large-format oil paintings to small ink wash works and rapid sketches.

It is apparent that Lysovenko is fond of establishing dialogue with classic Ukrainian (and Central European) painting, surfing the borderline of realism and social realism in her polemic, and willingly exploring the classic sense of style.

In a text accompanying the exhibition Cemetery Garden, Lysovenko describes her impression of the encounter with the Wall of Remembrance, a monumental bas-relief by Ada Rybachuk i Vladimir Melnichenko[4]. The allusion seems to be carrying particular power in referencing a work focusing on historical memory and oblivion, one restored from an abyss of non-existence. The Wall was erected with tremendous effort and in a particular location; censored by authorities, it was poured out in concrete. Its minuscule section was unveiled as part of the Kyiv Art Week in 2018[5]. Russian aggression has questioned the likelihood of extracting the entire work from beneath its concrete coating.

Creating her own “diaristic reality”[6] and aware of the potential loss of a part of her works, Lysovenko has amazingly found her own space in the symbolical lacework. It ought to be forcefully emphasised that Lysovenko is not fetishizing or pornographising the image of war and suffering. She unfolds her tale of a painter, woman, mother, daughter and guardian of individual and collective stories – confronted with the here and now. Thus interpreted, Lysovenko’s art is extraordinarily feminine and extraordinarily historical.

Translated by Aleksandra Sobczak-Kövesi

[1] K. Lysovenko, untitled, text accompanying her exhibition at the “Arsenal” Gallery in Białystok, https://galeria-arsenal.pl/wystawy/kateryna-lysovenko-ogrod-cmentarny (accessed on May 22nd 2022).

[2] Defined as: half-female, half-bird, or half-female, half-fish.

[3] See https://secondaryarchive.org/artists/kateryna-lysovenko/ (accessed on May 21st 2022).

[4] K. Lysovenko, op. cit., see also Dlaczego w sztuce ukraińskiej są wielkie artystki (Why Are there Great Female Artists in Ukrainian Art), ed. K. Yakovlenko, Warsaw 2020, pp. 24-25.

[5] “Last month, a small section of the concrete was ceremonially chipped away to mark the start of Kyiv Art Week. It is hoped that a crowdfunding campaign will result in the removal of the rest”, A. House writes in the piece ‘How the city of Kyiv is reckoning with its Soviet past’, Apollo. The International Art Magazine, June 11th 2018, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/kyiv-art-week-2018/ (accessed on May 21st 2022).

[6] In using the term, I am quoting P. Rodak, see e.g. Między zapisem a literaturą. Dziennik polskiego pisarza w XX wieku (Between Record and Literature. A 20th-century Journal of a Polish Writer), Warsaw 2011.

The Arsenal Multicultural Playground

The Arsenal Playground is opening up even more to its multicultural audiences, offering them access to one-half of all Gallery salons throughout the term of Kateryna Lysovenko’s exhibition. Tailormade to fit different age groups, workshops, film screenings and psychological sessions will be held in Belarusian, Polish and Ukrainian on premises separated from exhibition rooms. A detailed activity schedule will be published shortly.

Concept and co-ordination:

Ewa Chacianowska, Katarzyna Kida, Justyna Kołodko-Bietkał, Małgorzata Kopciewska, Izabela Liżewska, Roksana Mroczko, Eliza Urwanowicz-Rojecka

Translated by Aleksandra Sobczak-Kövesi

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30