JAROSŁAW KOZAKIEWICZ – Geometry of the inside

Andreas Schlaegel

Several Considerations on the Lost Ear

“Yes, that’s a human ear all right.”

1

“Yes, that’s a human ear all right.” Uttering these words, detective John Williams put his find back in the brown paper bag held under his nose by the dumbfounded Jeffrey. Found on a lawn in a provincial American town and colonized by ants, the grimy ear from David Lynch’s classic Blue Velvet is probably the most famous ear in cinematic history. “Why an ear?” the director was asked during a New York Times interview accompanying the film’s 1986 premiere. To which he answered, “I don’t know why it had to be an ear. Aside from the fact that it had to be a bodily orifice, an opening leading into something else… The ear is situated on the head and leads directly into the human brain. That’s why it seemed like the perfect choice.” The significance of the ear lies not in its ability to hear, but in the direct access it offers to the viewer’s mind. Not only because what is seen does not always overlap with what may be expressed in words, but because these two can even enter into competition. The bodiless ear in Blue Velvet constitutes a narrative and a symbolic entrance into the complex, beautiful and gruesome history of the ear.

2

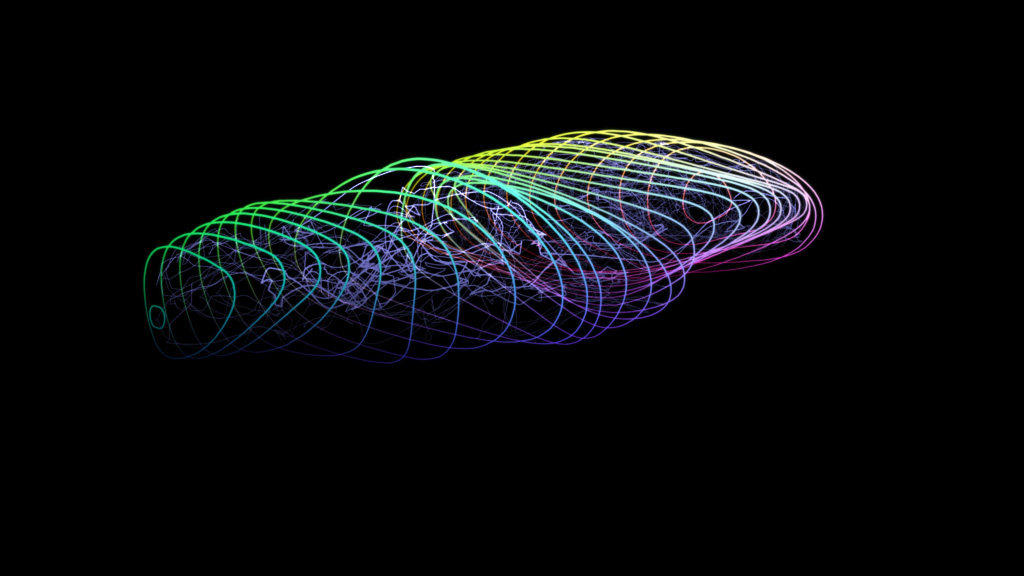

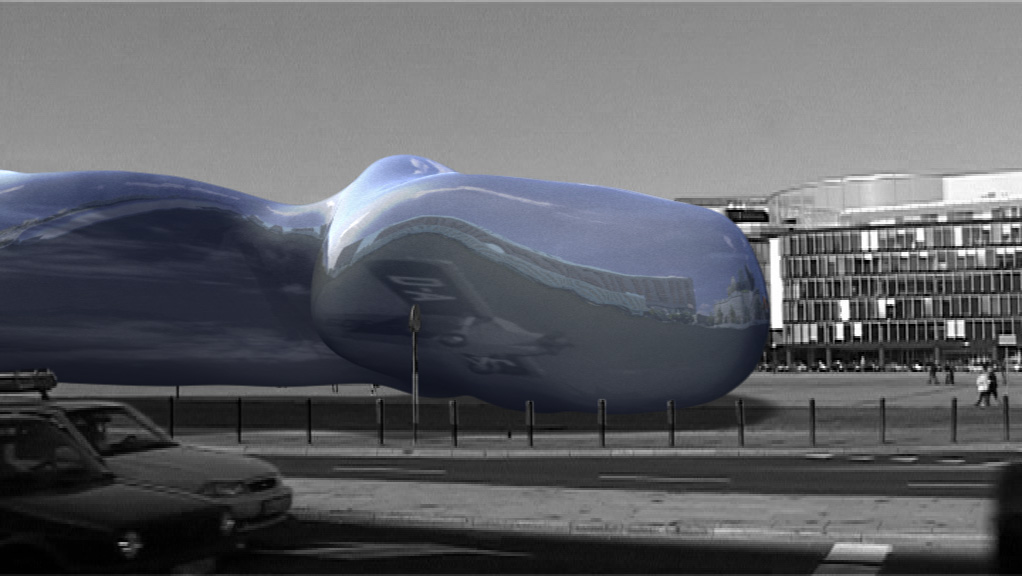

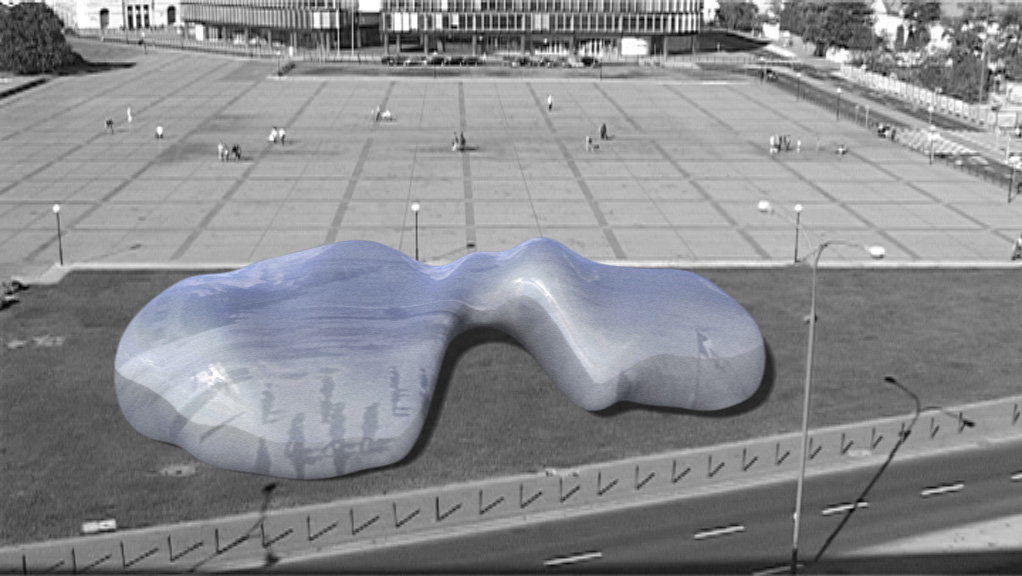

In the Lusatian Lakeland, Polish artist Jarosław Kozakiewicz created a sculpture of a gigantic ear, an architectural earthwork in the shape of a monumental auricle, larger than the Alliance-Arena in Munich or the Olympic Stadium in Berlin. Due to the sheer size of the object, which is 250 x 350 m, viewers standing inside may have difficulty realizing where they actually are. Being at the same time an example of artistic landscape, architecture and sculpture, it may provide a kind of juncture. But who does this ear belong to? 3

According to a largely unfounded myth which glorifies the artist’s image to this day, Vincent van Gogh gave a piece of his ear, wrapped in paper, to a prostitute. Many regard this act of self-mutilation as a genuine expression not only of the artist’s deep inner turmoil, but also of the alleged proximity of genius and insanity, serving as proof of his quality as an artist. Even if the act of cutting off an ear does not in fact impair one’s hearing, it seems as if the artist did not want to hear any more, as if he symbolically gave away this access to his mind. But sound detection is not the sole function of the ear. An organ in the inner ear, the cochlea, is designed to help us maintain balance. Therefore, ear loss may also be interpreted as loss of inner balance. A hundred years after van Gogh’s death, in a BBC show, another auricle was seen – on the back of a lab mouse. The ear was deaf, as the experiment was concerned with organ transplantation rather than improvement of sensory perception in mice. Doctor Charles Vacanti formed a polymer scaffolding in the shape of a human ear and sewed it on the back of the mouse. The experiment proved successful, and the ear was accepted by the mouse’s body which grew extra blood vessels to nourish its tissues. The ear was gradually covered with delicate fuzz, as the mouse lived on, seemingly undisturbed by the extraordinary growth on its back. Yet another reason why this lonely ear might seem a bit eerie and misplaced is that it breaks the symmetry of the senses manifest on human and animal faces.

4

This is why the unrealizable tree-house, Oxygen Tower, designed in the shape of the lobes of human lungs, seems so complete and perfect – the symmetry was left intact. The viewer can imagine that whoever enters the building will enjoy a visit to an observation tower and a flush of fresh, oxygenated air. Whether conceptual art, monumental architecture, or an accessible sculpture, the structure possesses therapeutic qualities. Breathing is a symbol of life, just like the tree, winding through glassmade lungs and providing them with oxygen. Does the tree form a scaffolding supporting these gigantic lungs? Should it collapse, the glass lungs would doubtless be destroyed. A tree-house and a life-tree, represented by artists as a place of regeneration and retreat from the joyless and hostile environment of deprived urban areas.

5

In Boxberg, grass is growing over the soft, dynamic hills which form the shape of a monumental ear. It is situated in an extensive landscape park developed with the thought of healing and recultivating the wounds inflicted on the landscape by a lignite strip mine. Symbolically, through its title, ‘Mars’, the earthwork ear refers to the artist’s idiosyncratic cosmology, establishing a connection between various European locations, planets of the Solar System, and the human body. Thereby, separation of the ear and the body, of hearing and understanding, cannot be easily reversed. Even if hearing is crucial to understanding, the things we hear lack a certain definiteness which may only be offered by the sense of vision, providing an overview and allowing for identification and location. This inconsistency of meaning between seeing and hearing generated by the separation of image and sound has been turned into a stylistic device in film, with a shot or a scream coming from off-screen and the viewers unaware of who was shooting or screaming. When they are first allowed a glimpse of the corpse, the killer has already disappeared. Perhaps the large ear would make it possible to communicate with the Earth. There is an amphitheatre to be developed inside the auricle in the future to host concerts or film screenings. Surely, visitors will also be able to see Blue Velvet, looking even smaller themselves than the ants on the ear in David Lynch’s film.

translated from German by Beata Kander

Curator: Magdalena GodlewskaJarosław Kozakiewicz

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30