Are we surprised by the statement expressed in the title? If not, why aren’t we? Have we gotten used to the unreliability of the media which evaluate cultural events according to their effectiveness on the one hand and their accessibility on the other? Have we become reconciled to the hostile attitude of clerks who treat art as a costly whim and who create hierarchies of cultural institutions, with galleries invariably at the far end as the least useful and the most bothersome? Do we treat as natural not only the destitution but also the indolence and a lack of professional attitude on the part of cultural institutions? If so, we live in a post-communist country, possibly in Poland.

Art life in Poland after 2000, although very vibrant, has not attracted much social interest, which is however steadily rising. Art, which displays a high quality level and is ubiquitous in Polish reality, is suffering from an absence of dialogue with intellectuals. While it has all the makings of being an important driver of social processes, it is alienated. This state of affairs in Polish art has led to the creation of a great many self-referential works, to an enhanced reflection on the status of art and art criticism, on the role and position of the artist, on the mission of cultural institutions, or threats in the art market. For the first time ever artists have taken up, or rather initiated a discourse which has so far been evidently ailing or non-existent.

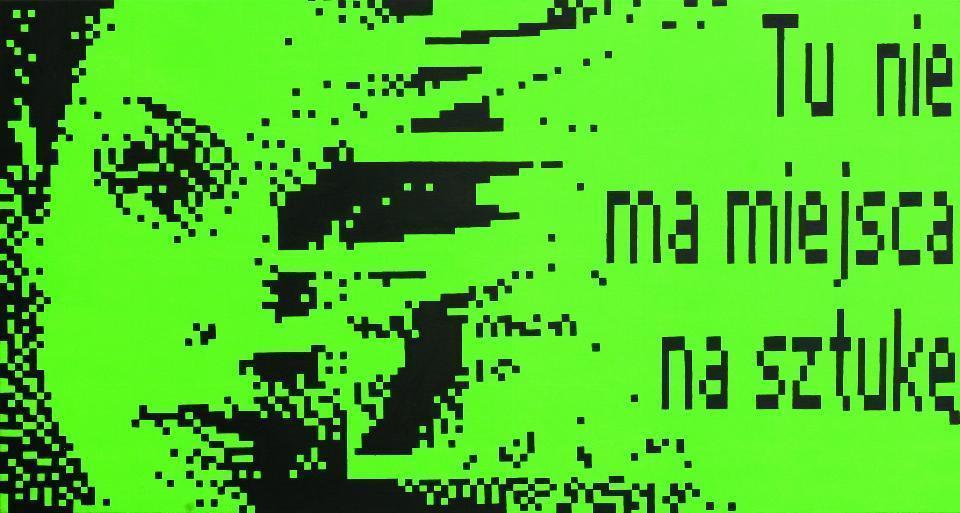

For years we have complained about a deficiency of insightful critical texts, about insufficient education in the field of the arts, and a disparaging attitude to contemporary art. Artists have accepted the obligation of a critical analysis of this state of affairs. The pride of place here is held by the Super Group Azorro composed of four artists: Oskar Dawicki, Igor Krenz, Łukasz Skąpski, and Wojciech Niedzielko. Their films have captured our imagination through and through, gaining the status of cult products similar to Monty Python’s movies. Can Artist Make Anything?, The End of Art, Everything Has Been Done, The Best Gallery, Portrait with a Curator and many others provide the most ironic and at the same time pretty accurate diagnosis of the world of art. We regard ourselves in these films as if in a mirror. It was Azorro’s Hamlet, a work about the status of an artist from a post-communist country, from a rightful yet still worse off part of Europe, that touched on the subject of art about art in the collection of the Arsenal Gallery and the Podlaskie Association for the Promotion of Fine Arts, presented during the current exhibition. Bitter irony is evident also in a painting representing a display of a cell phone There’s No Place for Art Here by Laura Pawela, and in the existential self-portrait of the Magisters group entitled Very High Degree of Self-Consciousness.

Paweł Susid introduces in between his abstract forms short sarcastic texts, smart commentaries on the surrounding reality. They frequently touch upon art: I don’t think I’ve seen you at an exhibition of contemporary art lately, I paint pictures once more if they are beautiful, It seems to me, pals, that we won’t beat television when it comes to images. Susid’s paintings perform a role similar to posters, where words, apart from conveying a particular message, are artistic signs. Actually, the work on display requires no commentary: …I regret to say that in my time many of my artist-colleagues catered to the pedestrian tastes of clerks and oftentimes of the state….

Of special importance in this collection are works dedicated to other artists. Frequently they are triggered by the artists’ sense of a lack of interest and their opposition to the neglect of those who influenced the domain of art before them. Vesna Bukowec, addressing the educational role of art, poses the questions Is Art Necessary? Why?, and then matches the answers she receives from viewers with the works of renowned artists.

Zbigniew Libera’s 2004 series titled The Masters is very telling. It is a series of press articles about artists who have turned out to be not good enough for ambitious media editors or incomprehensible for not too knowledgeable authors. Texts about them appeared in the press, e.g. in ‘Polityka’, ‘Trybuna Ludu’ and ‘Gazeta Wyborcza’. The last daily, on the front page of its ‘Gazeta Magazyn’ supplement, published an obituary of Andrzej Partum and an interview with Jan Świdziński. Naturally, Libera’s The Masters are forgeries that tell the untold and (under the present circumstances) untellable. Simultaneously, the work is an hommage paid to Libera’s artistic authorities.

The motif of an hommage appears also in the work by Ewa Partum that transposes Malevich’s black square onto a road sign, in a video by Anna Molska Tanagram, and finally in the works by the Sędzia Główny (Chief Judge) group (Karolina Wiktor and Aleksandra Kubiak), which are posed photographs dedicated to renowned Polish artists, Natalia LL and Zofia Kulik. However, in this last instance a question arises – is the Hommage that appears in the title a genuine token of respect? Or rather, by assuming the roles of their predecessors, are not the artists more interested in confrontation, checking their own efficiency; are not these self-reflexive works?

Artists’ egocentrism seems their natural privilege; the artist had better be self-centred. When witnessing an artist’s in-depth self-analysis, we ourselves arrive at self-knowledge. Izabella Gustowska in her video Wonderful Life regards herself without affectation, from a distance, confident that genuine information is inaccessible. The artist shows herself to us in every possible aspect and everyday details, making us acutely aware that we will never learn the truth and that the truth about her is equally inaccessible.

In the Artist for Rent project Joanna Rajkowska, working with others to solve their everyday problems, invalidates her privileged status of an artist. Thus it is no longer art but the artist herself who becomes generally accessible. Rajkowska decides to listen to stories of ordinary people and make the participants of her project the first and most important recipients of the work. By assisting them, she assists herself, too, trying to re-define her own identity with respect to the art market.

Oskar Dawicki commissioned an MA thesis about himself through the Internet. This document about a famous performer, written in a quasi-scholarly language, purports to be a scientific dissertation and at the same time undermines the credibility of scientific sources. As Dawicki claims, this is an “academic bubble foil” he has wrapped himself in.

The question posed in the title of Maciej Kurak’s work: Is it important who hides behind a painting? is in point of fact a question about the meaning of a work of art, about what grants such status to a particular object. And if this is contingent on the decision of the artist, who is the artist and how is our assessment of a work of art dependent on the knowledge about its author?

Agnieszka Polska makes use of a subversive trick, recording objects that might seem works of art. Thus she tests our confidence that something is or is not art. Rafał Bujnowski, working on a realist landscape, takes it to the point of abstraction. Artists themselves undermine the significance and meaning of art, test it and dismantle into component parts.

The art market in Poland is a new and moreover a longed-after and long-awaited phenomenon. It might seem that it is too early to contest it. In The Midget Gallery project Katarzyna Kozyra dispassionately addresses the institutions of art biennales and fairs. She keeps a record of her activity as a performer and organiser, sets up a biennale that is competitive with respect to the Berlin one and releases the “midget” virus into the art fair in Basel. The work transposes discourse from the local to the universal, but does not facilitate an answer to the question whether art is important. A similar situation obtains in the case of the woollen portrait of the Arsenal Gallery by Julita Wójcik, an artist who consistently de-mythologises the artist’s ethos.

The works on display make us aware of how far we have departed from the Romantic paradigm of the author and work so much cherished by Polish audiences. The legacy of this paradigm seems a source of misunderstandings and difficulties in addressing contemporary art. We need to take a lot of effort, indeed, so that art might become meaningful not only for us.

Monika Szewczyk

translated by Marcin Turski

Purchase of art works for the collection:

partially funded from the means of the Minister of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland

partially funded from the budget of the City of Białystok

and realized with financial support of the Podlaskie Voivodeship Marshal’s Office

Curator:

Monika SzewczykAzorro, Babi Badalov, Rafał Bujnowski, Vesna Bukovec, Oskar Dawicki, David Diao, Paweł Dziemian, Jakup Ferri, Izabella Gustowska, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Elżbieta Jabłońska, Zuzanna Janin, Alevtina Kakhidze, Katarzyna Kozyra, Maciej Kurak, Norman Leto, Zbigniew Libera, Magisters, Marcin Maciejowski, Joanna Malinowska, Anna Molska, Tomasz Mróz, Ewa Partum, Laura Pawela, Agnieszka Polska, Joanna Rajkowska, R.E.P., Sędzia Główny, Marek Sobczyk, Paweł Susid, Twożywo, Julita Wójcik, Karolina Zdunek