Hubert Czerepok. The Beginning, as a part of festival the Rise of Eastern Culture / Another Dimension

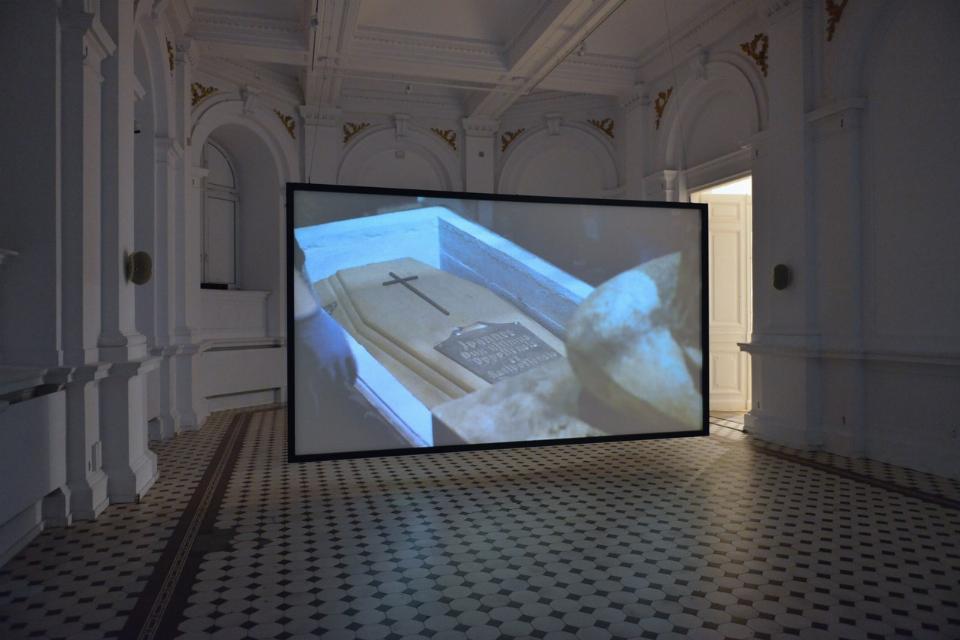

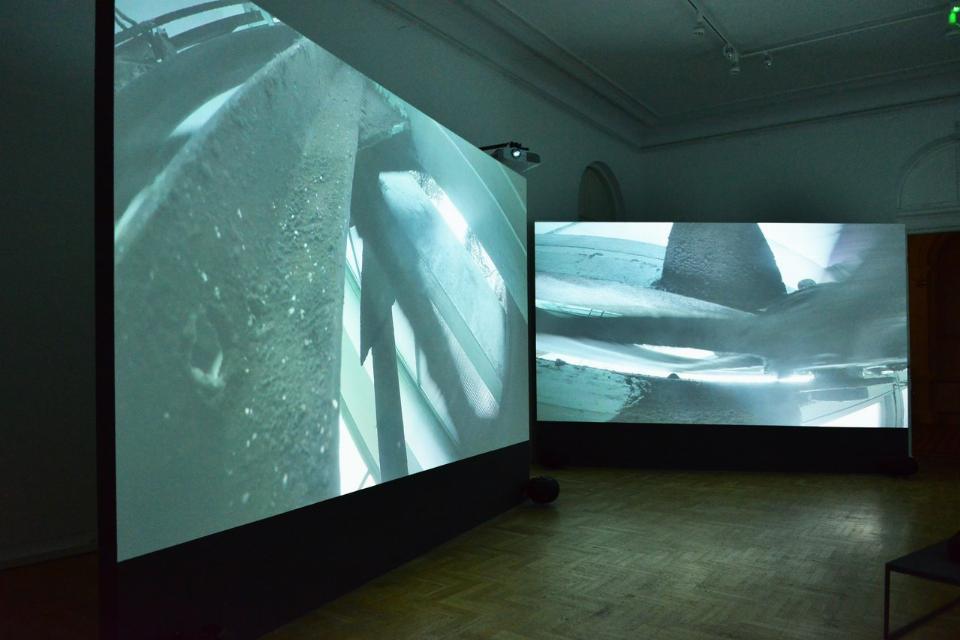

The exhibition consists of three video installations. The first one is a three channel projection realised at the site of the archaeological excavations at Karahan Tepe, Turkey, where the oldest site of worship – dating back to 10 thousand years BC and believed to be a cradle of civilisation – was discovered.

It was even before the neolithic revolution, before the beginning of agriculture and animal breeding, that the oval structures made of adhering megalithic pillars had been created there. What civilisation managed to accomplish this, who were the people who buried the sanctuary 1500 years later and why – remains a mystery.

The artist analyses various theories concerning the origins of this extraordinary place, comparing the expedition to such distant past to a travel to Mars, and referring to Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker. In this film, the narrative is led by three characters: the Writer (man of arts), the Professor (man of science) and the Stalker symbolising spirituality. In Hubert Czerepok’s work, these three perspectives are embodied by three robots – Mars rovers.

Another part of the project is a three-channel video Continuation – a visual story of an old, post-industrial cable car network in the Georgian city of Chiatura, which has been operating almost continuously since 1953. It was built to transport miners working in nearby mines. Although 60 years has passed, it was still the most convenient and fastest way to move people around the city. The artist managed to complete his work just before the tram was modernised in the autumn 2016.

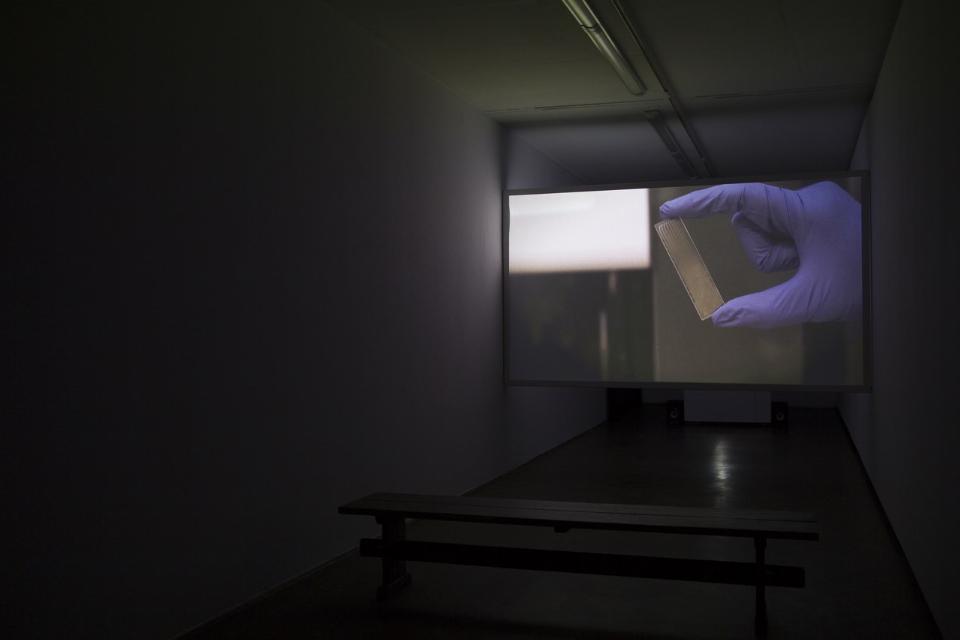

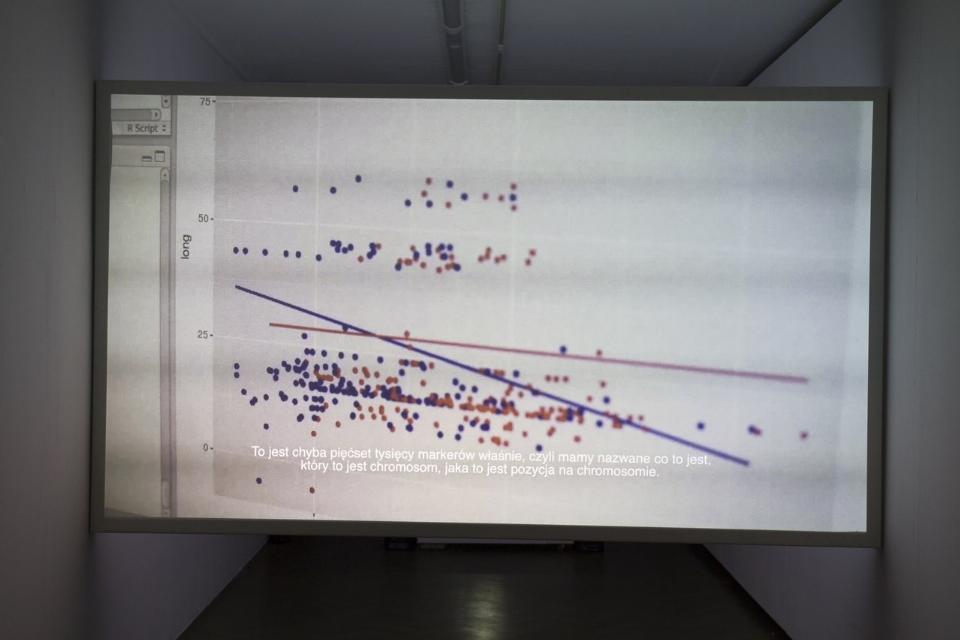

The title of the exhibition was taken from another video work – a documentary film showing the DNA research of the first Piasts and the hypothesis about their foreign origin, which was created in the 19th century. One of its first supporters was Karol Szajnoch. In 1858, he presented the thesis that in the 6th century Scandinavian immigrants called Lachs came to the Polish land. Another version of this theory was presented in 1918 by two German historians Lambert Schulte and Robert Holtzmann. They referred to a document called Dagome Iudex, in which Mieszko I (called Dagome) places his land under the protection of the pope. Based on this, the German scholars deducted that this was probably a Danish leader named Dago who, around 960, conquered the land around the Warta River. For two years, the Institute of Organic Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Poznań has been carrying out a research project which is supposed to finally solve the mystery of the origin of Mieszko I and the Piast dynasty.

In the works presented at the exhibition, fiction is mixed with science, many hypotheses and theories broaden our view of the complex and ambiguous reality and cause the question of the origin to remain open.

This text was originally published on the Hubert Czerepok, The Beginning exbibition’s website, Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, [online:] https://zacheta.art.pl/en/wystawy/hubert-czerepok-poczatek?setlang=1, [acess: 17.07.2018].

The exhibition is organised as a part of the Festival Rise of Eastern Culture / Another Dimension

Hubert Czerepok talks to Monika Szewczyk

I was always impressed by the range of your projects. By your erudition, by how many areas you tackle, and how many various media you apply. Yet, from among all the exhibitions I remember, the preparation of this one, for Zachęta, seems the most complicated in terms of logistics.

I suppose this is because I show three new films here, each of them requiring all the preparation and production stages that are very time consuming. Also, two of them are set in very distant locations, and the third one very near, but in a guarded and secret place.

You have a soft spot for mythical places, ambiguous situations, solving mysteries, conspiracy theories, for finding things which are not accessible to everyone, hidden under the surface. Does it require a lot of research?

It happens quite naturally. I am simply interested in the things that are hidden under the carpet or between floor panels. Maybe because this is exactly where most information about the users, the residents is hidden. And this is why those films are about dwellers and users of the world we live in.

Could you tell us more about those films?

The first one is about the future. About a dystopian future, which may become our destiny, when there are no more minerals to be mined, when there is no more fuel, and everybody will have to take care of the technology that remains. The film is set in Georgia, in the town of Chiatura with numerous manganese mines. The manganese mining boom took place at the beginning of the 20th century, when local mines were responsible for 1/3 of world manganese production. Later, the Russian empire took over, and when it fell apart and Georgia regained liberty, the production stopped. The city declined. I was fascinated by the fact, that a a whole network of cable cars was constructed for the needs of the miners, connecting the parts of the city located on the top of the canyon with those in the valley. Primarily they were designed to transport the miners to work. The mines enabled whole families to dwell. Now, the cable cars are still the most convenient means of public transportation; although they fall apart, become covered with rust, they are still kept alive thanks to human hard work. There are no charges for using this means of public transportation. Maybe this a model for the future cities with free transportation.

A community project.

Yes, this is a community project. Without it getting from one part of the city to another would take many hours by car, because you have to drive around the whole valley. It is incredible to what extent this mechanical organism requires human dedication. It is like a situation from the future, when we will only have a small number of machines left and we will have to take special care of them in order to keep them operating. They then become part of the community, and the people which operate them start to act as machines, which have to deliver their work for many hours.

Am I right, that the cars are being pulled down at the moment? You managed to capture this place in the very last moment, and your film is also a documentation of something there ceases to exist.

Yes. When we arrived there in November 2016, two or three of the cars were already out of order. Georgia received financing for pulling down the old cars and replacing them with a new infrastructure. There are two companies that count on the cable car market. One from Switzerland, one from France. They construct the cars that we can see everywhere, e.g. at ski slopes. It is a kind of global cable car system. I know this is much safer, and maybe prettier, but even cable cars try to look alike. In our country the longing for prosperity also leads to getting rid of objects which create history.

These places have also a sentimental value, so important in human life. When they disappear, we lose something essential.

Yes. This is the context connecting this project with the other film, which was shot in Turkey. In 1994, a German archeologist Klaus Schmidt began excavations in Göbekli Tepe — a place which was discovered by a farmer working in the field. It turned out that under the soil the oldest neolithic sanctuary on Earth can be found, dating circa ten thousand years BC. Why are these two projects connected by the context of loss? Because the hill wasn’t a natural construction. First there was a shrine there, around nine thousand years BC it was abandoned by the people, who lived there, covered with soil, hidden, hibernated for thousands of years. We find it and we know nothing about that civilisation, what people lived in that area. We know one thing, that they changed their lifestyle from huntersgatherers to settlers. They also created the first images of animals, the first sculpture representing the human figure, but first of all they invented God, somebody who is above, and thanks to whom they exist. They stopped praying to atmospheric phenomena. For some reason, after 1500 years, the same people abandoned their temple. They decided to hide it and migrate. Where to?

The decision to bury the temple is a symbolic one, but not fully understandable. Was it a kind of camouflage?

I understand it as a gesture of hiding something precious from desecration. Creating a safe hideout. The limestone pillars that were found there create circular structures, five to seven meters long. They were buried in such a way that only very small fragments are visible. They look like ordinary stones in the middle of a field.

Maybe it’s just the impact of time and natural conditions, such as sand storms?

No. The researchers are unanimous that the shrine was purposefully buried. Initially the film was to take place at Göbekli Tepe, but when we went there for scouting, we found out that the place is quite dug up. Metaphorically speaking. Many excavations are being conducted there and a whole tourist infrastructure is being created. I thought that it doesn’t fit anymore into the vision of a mysterious place where civilisation was born. Göbekli Tepe became a museum. But I found outthat there is another hill, located around 50–60 kilometers from the first one, also hiding a shrine from the same period, maybe even a slightly older one. Slightly meaning several hundred years. The other shrine doesn’t have so many images of animals, plants and people. It was create earlier, the stones are more roughly carved. It would mean, that the people who build it weren’t ready for such full imaging. The place is called Karahan Tepe, located near a small town Keçili. It is a settlement in the Tektek mountains, its name means ‘wasteland’ (the hill is actually a wasteland). At the beginning of the 21st century a Turkish archeologist Bahattin Çelik found a shrine covered with soil there, built of 266 huge stone pillars creating circles. It fills the whole hill, the scale is unbelievable. There are two neolithic amphitheaters, partially carved in stone. A unique place where man invented theatre (and what follows – cinema), and art. When man was in constant motion, hunting, gathering, he didn’t need entertainments. When he settled he began to feel such need, he found time, both to believe and to create art.

Science, research, situations which are checked and historically confirmed. You very often refer to history. Do you manipulate the found material, modify it somehow? Or are these stories fascinating enough, and you can just faithfully convey them and treat them as an attractive, intriguing and not so obvious subject.

I am not a documentarist, it is more of a creation. What is fascinating in reality is the fact, that it can have many possible interpretations, and everybody can describe what they see in their own way.

Usually this is what happens. I have an impression that even when looking at the same things, we see something different, not the objective reality, but rather an imagined one.

It allows us to describe the events in various ways. Let’s be honest – in most cases history doesn’t consist of facts but of speculations. The third film refers to such narrative. It is about the beginning of the Polish state, the dynasty of Piasts. Let’s imagine that in some miraculous way the Piasts conquer and subordinate subsequent tribes, and thanks to that our country is created under the rule of Mieszko and later his son Bolesław who becomes the king. This looks like a sensible scenario. A credible one. In reality, there is only one document, Dagome Iudex, where a prince named Dagome is mentioned, supposedly he is Mieszko. It is the only historical document from that time. The rest of this well know narrative is composed of speculations by Wincenty Kadłubek, who invented that story and wrote it down several hundred years later.

The name Dagome suggests a different origin that Slavic.

There is a theory that I refer to in this film. There is an assumption that Mieszko’s fellowship, which may have consisted of several thousand brave knights, who helped him subjugate other tribes, was composed of warriors from the north. They were a mercenary army, payed for their services with land, fiefs, etc. We can suspect that Mieszko could be one of them. Otherwise why would several thousand recruits listen to some bulky blonde guy?

If he was blonde . . .

As a Slav he must have been blonde. Of course, the promise of remuneration could also be the motivation for the military.

Tribal loyalty sounds much better though.

Various research upon this subject is being conducted by many organisations, but I focus on just one of them. I’m interested in research conducted by professor Marek Figlerowicz from the Institute of Biochemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Poznań. It is a big research project, aiming at comparative DNA tests of the first Piasts and the Scandinavian dynasty. He told me recently that he is preparing a publication on this subject. He didn’t want to reveal any details, but the results may change our perception of history. After all, it seems that our history, older and newer is covered with soil. As simple as that. It only depends how much soil there is.

So we may be Vikings?

I thing each and every Pole has some amount of ‘foreign’ blood. The so called purity doesn’t exist. When I was in Turkey, in Urfa, near upper Euphrates and Tigris — rivers that gave beginning to civilisation – I had the feeling it actually was its cradle. That it all began at those plateaus – they are like a melting pot. People of many cultures live there, speaking various languages. People living around Urfa still use the Aramaic language, just like Jesus. It’s the only such group in the world. If somebody wants to listen to Aramaic language he should go there.

If we dig deeper, maybe we will find out that we are simply refugees from Syria.

A similar theory is presented in the film. There is a hypothesis that nine thousand years ago, the people who buried their shrines in Karahan Tepe and Göbekli Tepe, moved from Asia Minor to Europe, giving origin to Slavic and Germanic peoples. Neolithic temples built on the plan of a circle are present everywhere around Europe. This theory is unconfirmed. For me this an interesting issue, a challenge I want to face. If there are comparisons being made between the style of animal imagery from Göbekli Tepe and the one from the mountain of Ślęża, then there must be something about it.

Can we talk a bit more about your ‘Turkish’ film, where I noticed some traces of your much earlier productions, such as Armageddon, or Lux Aeterna, and your interest in science fiction films. Beginning is also quite straightforwardly inspired by Andrei Tarkowsky’s Stalker.

Yes, in this film machines are searching for spirituality. Why not? Once, at a Council at the Academy of Fine Arts [now University of Art] in Poznań a wonderful conceptual photographer and analyst presenting his photos heard the question about spirituality in his work. I thought it was some sort of a cynical joke, a question which was to spoil his Ph.D. exam. But from some perspective, I think that art actually may be in search of spirituality, even it is a completely different, post-humanist one.

This interview was originally published in: Zachęta lipiec, sierpień, wrzesień, październik 2017, Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw 2017, CC BY-SA.

Translated from Polish by Klara Kopcińska.

Related events:

A guided tour of the exhibition with an exhibition curator and artists: 1.09.2018, at 6 p.m.

Curator: Monika Szewczyk

Hubert Czerepok

(b. 1973, Słubice) — visual artist, author of installations, photographs, objects and films. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań, where in 1999 he made his diploma in Izabella Gustowska’s and Jan Berdyszak’s studios. Between 2002 and 2003, he completed postgraduate studies at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, and in 2004–2005 at the Higher Institute for Fine Arts in Antwerp. Assistant and then assistant professor at the Studio of Video at the Poznań University of Art. Currently associate professor at the Department of Painting and New Media of the Academy of Art in Szczecin, director of the Experimental Film Laboratory. He examines anomalies, strange and uncontrolled things, analyses constructs that determine human behaviour, tracks conspiracy theories and paranormal phenomena, looks for the rules of the Great Conspiracy, and mixes history with utopia. With exceptional erudition and sense of humour, he balances on the edge of ironic distance and authentic engagement.

Selected individual and collective exhibitions: History and Utopia, Arsenał Gallery in Białystok, 2013; Lux Aeterna, Żak/Branicka gallery, Berlin, 2012; Devil’s Island, La Criée Centre d’art contemporain, Rennes, 2009; Cultural Transference, EFA Project Space, The Elizabeth Foundation for The Art, New York, 2012; Houses as Silver as Tents, Zachęta — National Gallery of Arts, Warsaw, 2013; Regress/Progress, Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, 2012.

Array

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30