Communities – Young Art of Ukraine

Anna Łazar

Urban Guerrillas and Rural Sabotage: young Ukrainian artists’ way to attract viewers

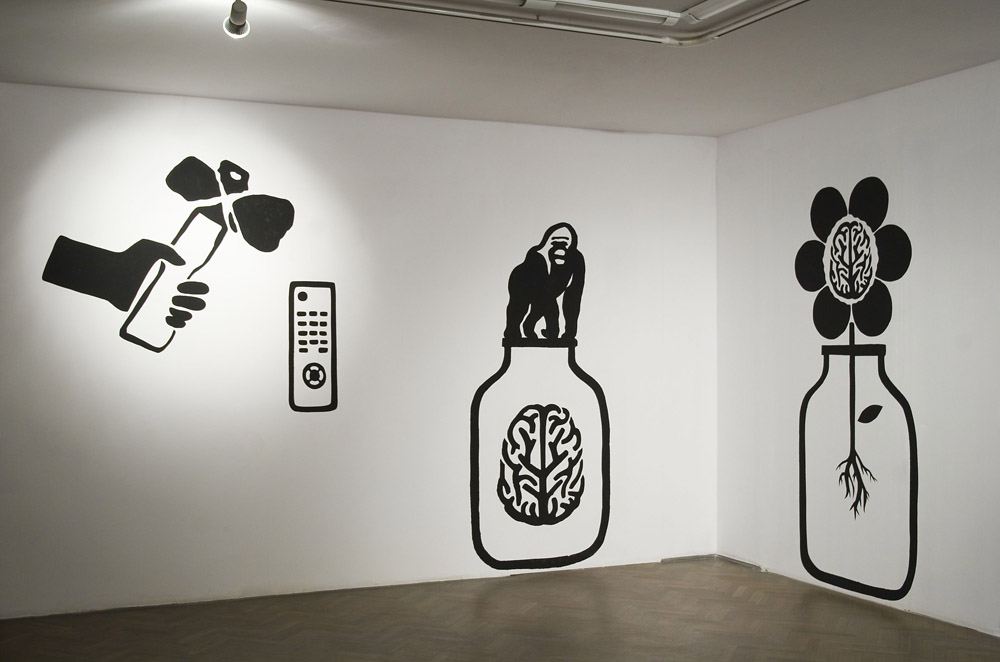

The exhibition entitled Communities. Young Art in Ukraine is the outcome of a project initiated in February 2007 by the Center of Contemporary Arts affiliated to the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (NaUKMA). The project required the artists to tackle such issues as the organization of their work and unconventional ways of attracting viewers. Nikita Kadan, a member of the Revolutionary Experimental Space art group (Ukr. ‘R.E.P.’), points out a specific reason why such issues need to be handled: “In Ukraine there is no integrated structure of contemporary art institutions . In fact, the stagnation of official artistic education, the want of curators and art critics, as well as the virtually non-existent interest in contemporary art among potential viewers prove quite successful in marginalizing young artists.”1 Nevertheless, young artists wish to make it clear that they intend to shape Ukrainian art anew; they refrain from imitation and strive to establish their own solutions. However, they sometimes do echo some ideas that were rejected elsewhere: “Self-education in a community is more effective and your colleagues may serve as critics; they also constitute an audience that evinces interest. This is how «the autonomous territory of art» turns out not to be a utopian concept but a genuine topos created by our generation.”2 Revolutionary rhetoric is one of the identifying features of R.E.P. In its manifesto, Kadan gives the audience and the critics a wide berth and proposes the idea of “autonomous territory of art”. All traditional roles are to be performed by the artists who are to create an affiliated community. The fact that such a community would remain quite hermetic has become the key charge against the so-called tusovka;3 it would be unfair, however, to level such a charge against artists who invariably have to negotiate with casual audience their existence in the urban and rural space and, at the same time, strive to seek contact with other artists. Yet, it seems that R.E.P.’s passionate manifestos do not serve merely as an illustration of their activities; they constitute a fundamental element in their own right. R.E.P. uses language that has long been reserved for making political claims, which means that at times it is also afflicted with detachment from tangible practices. In the beginning of 2006 in a performance entitled R.E.P. Party, members of the group impersonated an actual political party which wanted to draw voters’ attention. Dressed in white suits which resembled both a painter’s outfit and the type of clothing that protects against radiation, they stood by a black and white tent and vociferously familiarized the passers-by with their manifesto which voiced absurd demands to be fulfilled by culture. Such requests as “Spirituality for everyone” are bound to make people laugh; but more importantly, they should be viewed as a means of denouncing linguistic clichés, as a mirror image of politicians’ verbiage, and as a mark of the superficiality of the political scene. The project entitled We will R.E.P. you (2005) deserves particular attention. During the celebration of the anniversary of the October Revolution, masked artists carried portraits of Beuys and Warhol into Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square). When confronted with the representatives of communists, nationalists and accidental patriotic speakers, their presence and their demands, such as the famous “Jeder Mensch ein Künstler!” (Eng. ‘Everyone is an artist’), witnessed aversion rather than amusement. The interviewees seemed convinced that the presence of these oddly dressed people was not only illegitimate, but also that it was aimed at undermining and ridiculing serious demonstrators. Maybe this response was caused by the way the artists were dressed: they proposed their own convention which did not fit in with the idea of “staying themselves” to which all other people adhered. Although the recording did not register any direct acts of violence, the atmosphere was rather tense, regardless of the fact that the artists were peacefully inclined. When a priest used a loudspeaker to ask them to stop drumming when prayer was to be held, their reaction was positive. The latest project carried out by this leading Ukrainian art group is entitled Patriotism. It involves the creation of a pictographic language which would make communication without intermediaries possible. Particular images refer to words and concepts; when put together, they form witty, and sometimes critical, little puzzles.

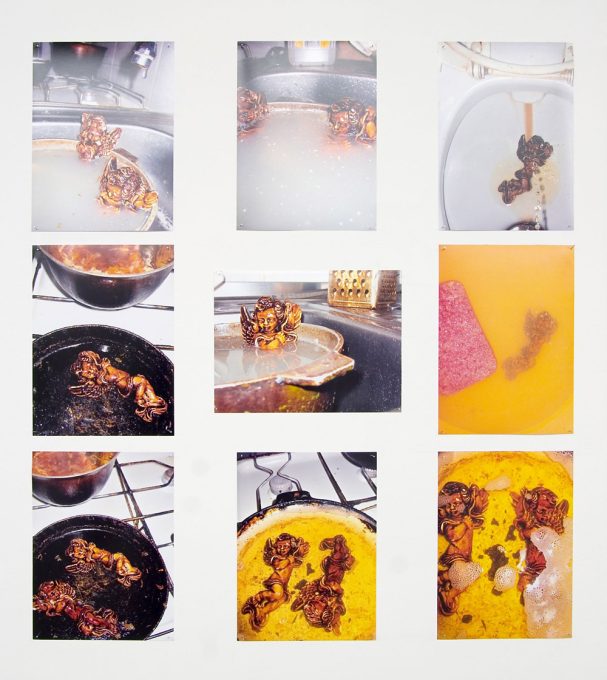

Other participants of Communities project also do not have to fear alienation. Mykola Ridniy, Ganna Kriventsova, Olena Polyashenko and Bella Logacheva form a group of artists based in Kharkov called SOSka. It was originally established in 2005 as a lab gallery and since 2006 Mykola Ridniy, Ganna Kriventsova and Sergiy Popov have also been operating as an art group. The mysterious name comes from a particular jargon and refers to prostitute who suffers from a venereal disease and infects her clients. This image is supposed to reflect the way the group functions; maybe this is how the artists try to make it explicit that their position may seem marginal, yet it may also be dangerous. Three performances were chosen for the exhibition. They Took to the Streets was performed a day prior to the parliamentary elections in 2006. Artists wore masks of Yulia Tymoshenko, Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych and begged in the streets of Kharkov and Kyiv. Faces from the front pages of the newspapers emerged from the anonymous and silent periphery. One of the shots captured the artists moving in a dense but wobbly group, which brings about associations with Pieter Bruegel’s painting entitled The Blind Leading The Blind. Is it possible that the fierce election campaign had led SOSka to such a reflection on Ukrainian political leaders? They surely disturbed the currently existing visual hierarchy. Barter, a project which was carried out in cooperation with the inhabitants of a village near Kharkov, is also worth mentioning. Mykola Ridniy tried to exchange printed versions of great works of contemporary art for foodstuffs. He would swap a Roy Liechtenstein for a jar of, say, pickled cucumbers. Ridniy did not provide any background information on the items he was offering. He was more curious about the reasons behind the client’s choice: more often than not it was about color and the painting’s resemblance to something familiar.

An international interdisciplinary group of artists affiliated as the Carpathian Theatre also ventured into the countryside. The group was represented at the exhibition by Ivan Bazak, Claudia Stolle, Karla Fehlenberg, Benjamin Schälike, Gerhard Csejka, Oliver Skibbe and Jacek Szubert.

Bazak showed a footage of a wedding reception in a village in the Carpathia region. The recording was introduced by a text from Illustrierter Führer durch Galizien (Eng. ‘An Illustrated Guide to Galicia’), published in 1914, which describes the customs of the Hutsuls in the following manner:

Great freedom of sexual behaviors among men and women is one of the curiosities of the Hutsul life. Almost every married Hutsul man has a mistress (lubaska) and every married Hutsul woman has a lover. It is very often the case that sexual intercourses occur among members of one family: a father has an intercourse with a daughter, a grandfather has an intercourse with a granddaughter. Indeed, a father-in-law has a duty to make sure that a childless daughter-in-law bears children. The Hutslus remain completely unaware of the notion of marital fidelity and the above mentioned practices seem nothing out of the ordinary.4

This note makes the watching of the film, which was shot in such a way as to look like an amateur documentary, even more fascinating. The promiscuity signaled in the guide inclines the viewer to treat the newlyweds and the guests with suspicion. The artificiality of the entire situation makes itself conspicuous: the participants stay serious, focused and festive, yet they seem to be as if tacked on to the rite. The ceremony proceeds according to an established scenario which appears to be a clumsy adaptation of the rite to local conditions. This local character is made even more explicit by the Hutsul folk band with a real cimbalom player and the official in a folk attire. It is indeed fascinating to think of whatever happened to the sexual behaviors of the Hutsuls after almost a hundred years. It is never made clear who observes the scene because the cameraman hired by the newlyweds appears in some of the shots. Is it possible that it is some abstract objective eye of the spirit of the Enlightenment? Extraordinary landscapes by Jacek Szubert as well as the photographs by Claudia Stolle, Karla Fehlenberg and Gerhard Csejka exhibited in the same room emphasized the atmosphere of incompatibility, a breach in reality that was compelled by the recording.

Psia Krew and Totoro Garden art groups presented documentary evidence of their urban guerrilla “warfare”. The identifying signs of the former involve skulls made up of pixel-like squares painted in places which are hard to reach, or images of crocodiles with long jaws (gharials?). Totoro Garden commenced a project entitled God’s Cows (the title is a literal translation into English of a Ukrainian phrase Bozhi Korivky that is customarily used to refer to a ladybug) whose main objective involves sticking ladybugs to the walls of buildings of public institutions, to billboards and posters, and even to statues of national heroes. This carnival gesture disturbs the solemnity and clear significance of well-known and explicitly defined places.

In addition to video recordings of their actions, Kherson Art Community exhibited also a number of paintings. Oleksandr Pecherskiy and Oleksandr Zhukovskiy “live in the village of Bilozirka ten kilometers away from Kherson; when they are not painting, they make furniture for local grocery shops and keep watch on a cucumber plantation.”5 Kherson Art Community decided to exhibit evidence of their artistic output in the gallery. They also displayed two series of drawings by Yulia Volyazlovska (People with Huge Ears and Anatomic Drawings) and Stanislav Volyazlovsky’s erotic comic strips full of perverse humor. The series entitled A Tale about a Leg tells a story of a painter who had a limb sewn to his thigh by a malevolent surgeon, which caused considerable problems with urinating. The painter lost his popularity with women but he was well-liked by dogs instead. Kherson Art Community also produced a number of amateur films based on various Hollywood motifs, for instance a crocodile attacking a group of holidaymakers or an invasion of the aliens. Scarcity in terms of sets and costumes, as well as the manner of acting, brought about the need to search for hidden meanings. One probable interpretation might suggest that the artists mock the stereotype of people from post-Soviet countries who look up to the unattainable ideals of Western culture and try to clumsily adapt to their reality everything that for them seems to have originated in a better world. The artists say that their projects refer also to provincial conspiracy theories.

The documentary evidence of the young artists’ projects, which constituted the main part of the exhibition, seems to prove that they seek to reach audiences in places not anointed with art. An art gallery serves as a venue which is suitable for presenting the results of their findings. The most vital issues include the relations within the artistic environment as well as the establishment of a wide institutional and social context for art communities. The exhibition managed to capture the primary questions which it has somehow raised anew: “Who we are?” and “Where we are?” Maybe in post-communist countries the question “Where we are heading?” is marked too heavily to be answered lightheartedly.

Anna Łazar

translated by Katarzyna Sawicka

The text (Polish version) was originally published online in Obieg (www.obieg.pl),

then in the catalogue “Wspolnoty. Mloda sztuka Ukrainy” (“Communities. Young Art of Ukraine”), Galeria Arsenal, Bialystok 2008 (Polish and English versions)

1 Nikita Kadan, Communities. http://www.galeria-arsenal.pl/arsenal.php?id=345&typ=ano

It is worth noting that such a situation reveals the colonial complex of the Ukrainians which is manifests itself in the sense of their own imperfection that becomes conspicuous when juxtaposed with a hegemonic entity. As far as Ukraine is concerned, the role of the latter was initially occupied by the Russian empire and later by the USSR where there was no use in seeking models of institutional solutions. As a matter of fact, Russia was hardly a civilization model for the countries it conquered, even though it maintained military and political supremacy. This is why the role of a surrogate hegemonic leader was assumed by the West, which was not only rich but also versatile in terms of organizational structures. Artists who deal with this subject matter include: Mykola Riabchuk, Oksana Zabuzhko, Yuri Andrukhovych, Marko Pavlyshyn, Miroslav Shkandrij.

2 Ibidem.

3 The word tusovka was defined by Viktor Misiano as “a temporary form of artistic community which has no institutions, demonstrates no solidarity and exhibits no common values.” The concept of tusovka was thoroughly discussed in an interview entitled Viktor Misiano about the Russian art scene and its whereabouts (http://sekcja.org/miesiecznik.php?id_artykulu=145). Jarosław Klejnocki proposes profitariat as a Polish equivalent of the term. He defines it as “a peculiar, closely-knit and ossified order of influences; a hierarchical cultural order based on lobbying and clientelism which readily manifests itself in media discourse which resembles that of a feature article.” Klejnocki, Jarosław. “Lobbyści i felietoniści czyli w szponach profitariatu”. [in: Literatura w czasach zarazy. Szkice i polemiki. Warszawa: 2006. p. 38].

4 The text is an attachment to the work.

5 Caption at the exhibition entitled Communities.

Curator: Jerzy OnuchIvan Bazak

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30