Archiwalna

Common Sets

29.03.2015 – 03.05.2015

Galeria Arsenał, ul. A. Mickiewicza 2, Białystok

Objects from the collection of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok and the Podlaskie Association for the Promotion of Fine Arts, and public institutions of the Podlaskie Voivodeship:

Podlaskie Museum in Białystok (Art, Archaeology, and Ethnographic Departments) and its branches: History Museum, The Alfons Karny Museum of Sculpture,

Museum in Tykocin, Palace Museum in Choroszcz

Museum in Tykocin, Palace Museum in Choroszcz

Wigry Museum of the Wigry National Park

Nature and Forest Museum of the Białowieża National Park

Post Brothers

A set of sets

The concept of the set is said to be the foundation of mathematics, a “gathering together into a whole of definite, distinct objects of our perception or of our thought” (G. Cantor). Sets are propositions used to describe, formalize, and construct relations, fields of objects that have been grouped according to certain structures and formats. A new set can be constructed by determining which members two sets have “in common” (often illustrated through a shared space where two fields converge). This space of intersection is called a “common set”, where collections or classes of objects come to occupy the same field and relate as part of a discrete body of information, an operative aggregate, a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

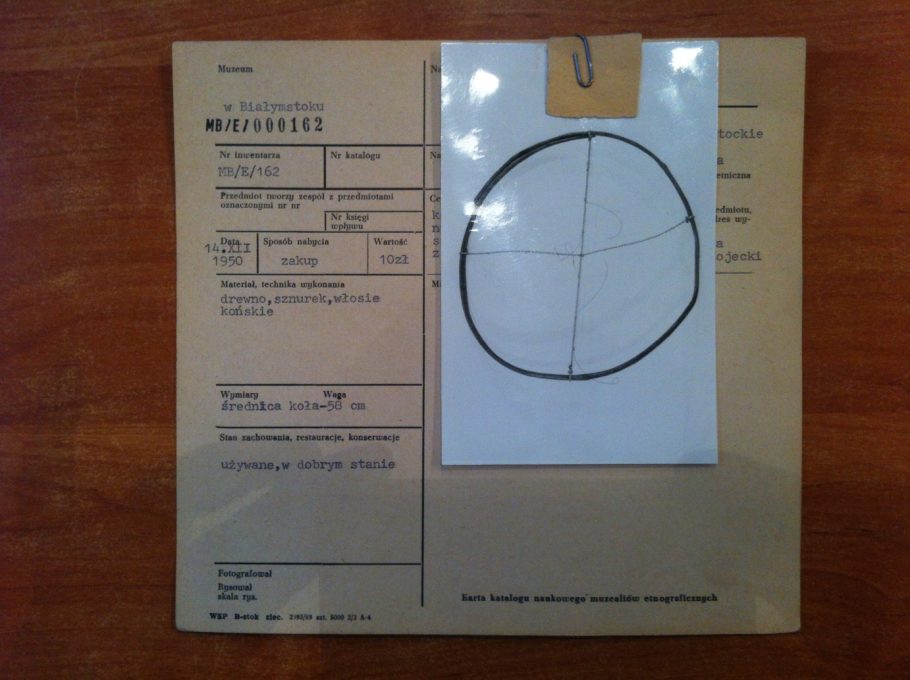

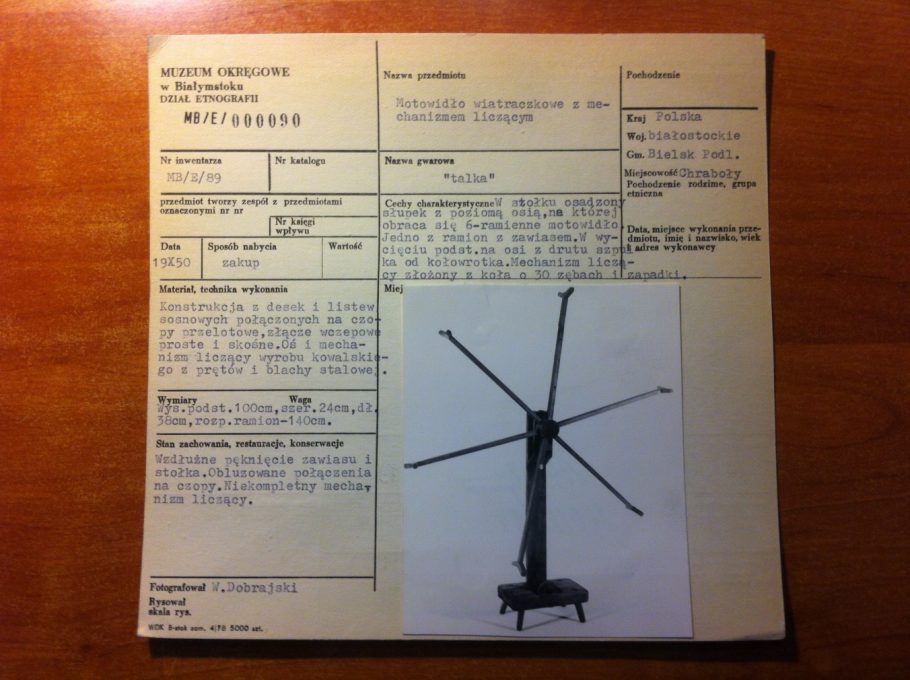

Curiously, the collections of many museums are referred to as “common sets”. This phrase not only describes the objects within individual magazines as sharing properties or organizing logics, but also refers to the concept that the museum’s artifacts are common property, belonging to society at large, producing a collective narrative through the accumulation of things. The exhibition “Common Sets” explores the collective set of sets that is formed within the region of Podlasie, commingling contemporary art objects from the collections of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok and the Podlaskie Association for the Promotion of Fine Arts with artifacts, documents, specimens, and objects drawn from the heterogeneous holdings of the Art, Archaeology, and Ethnographic Departments of the Podlaskie Museum and its branches: History Museum, The Alfons Karny Museum of Sculpture, Museum in Tykocin, Palace Museum in Choroszcz; as well as the natural history Wigry Museum of the Wigry National Park, and the Nature and Forest Museum of the Białowieża National Park. In combination, the variegated materials form an intriguing image of Podlasie, an archive of the commons that is both reflective of the shared histories, values and traditions within the region (an overlap of Polish, Belarusian, Lithuanian, German, Ukrainian, Russian, and Jewish cultures), and representative of certain logics guiding the collection of objects in the public domain as a whole. Comparing and contrasting the objects by placing them within shared zones of interaction, the curator Agnieszka Tarasiuk not only makes visible fundamental and shared ideologies at the core of public collections, but also scrutinizes the symbolic and structural procedures that orient how such civic collections are interpreted, framed, and become emblematic of certain bodies of knowledge or organizing principles.

Paramount to this exercise is an inquiry into the origins of museums as repositories of knowledge organized and maintained for the public good, a product of the Enlightenment’s emphasis on order, reason, reductionism, analysis, individualism, and civic representation. Museums are a system of representation that frames and contextualizes objects within certain narratives, identifying historical significance, cultural value, or the object’s status as “art,” while simultaneously excluding other phenomena. Together different museums act as coordinated and complementary systems within the Enlightenment project of commensurability—transcribing all human experience and expression into a universal frame of reference, where everything is meticulously categorized within an archive of the commons. Colliding varied sets of knowledge and collecting principles, the curator prompts the viewer to discern the interrelations between different methods of understanding and representation, and to discover potential hidden relationships.

When objects from distinct collections commingle in the exhibition, there is a mutual transformation. The first room highlights moments of abstraction found in quotidian materials and functional objects. A model of a 2006 installation by Monika Sosnowska even proposes the architectural reconfiguration of the Arsenal gallery space itself as an abstract form, a basic geometric format that can be reconstructed to produce new encounters. Here, often only the display of common objects changes their meaning and use. By exhibiting antique textile and farming tools including a bird trap, a stool, a spinning wheel, and a selection of axe blades, the curator ignores their functions and instead emphasizes the minimal and abstract forms of their practical constructions, therefore eroding the distinction between art and artifact. Literally extracting a fragment from the everyday and elevating it for aesthetic apprehension, Zhanna Kadyrova’sAsphalt cut–out (2011) is a well-worn slab of roadway asphalt that is presented unchanged, proposing the neutral units of public space as sites of abstract mark-making. Piotr Łakomy transforms readymade goods through subtle adjustments such polishing a laundry hanger and using it to loop music, therefore accentuating the formal properties of normally unremarkable objects. Where Kadyrova and Łakomy trade utility for aesthetics in their sources, Konrad Smoleński’s The End of Radio (2012) instead inverts the function of his readymade objects, reversing the signals of 194 microphones so that they become transmitters rather than receivers of information. The repetition of conventional forms is also present in a stack of concrete shelves from Mikołaj Smoczyński’s installation Library (1993), divulging both a bare practical purpose and a raw minimalism. While more ambiguous to their possible uses and referents, sculptures by Iza Tarasewicz and Małgorzata Niedzielko also borrow their materials, production methods, and forms from elementary shapes and conventional devices. Another instance of functional structure taking on an aesthetic role is the curator’s display of a wooden internal armature from a figurative sculpture, exposing a normally invisible frame so as to demonstrate the materiality, functionality and abstraction at the core of representations.

If there were a single object that represents the rest of the exhibition, it would surely be a bronze copy of an ancient sculpture of the Greek deity Hermes in the second room. The god of travel, contracts, exchange, passages, crossroads, transitions, social intercourse, invention, medicine, science, and mysticism, Hermes is an apt hero for the intersection of heterogeneous forms of knowledge celebrated by the exhibition, an icon for the crossing of disciplinary boundaries. Furthermore, the object itself is emblematic of the specific historical and cultural position of Podlasie itself. Forged across the country in Szczecin in the 19th century, the statue was likely dropped by Russian soldiers on their way back from the war front. Someone in the region found the fallen trickster and brought it in to be transmuted into a church bell, but it was recovered and accessioned into a museum collection.

Certainly the most overt way that a society visualizes itself and its values is through figuration. For many, a museum is not a museum without classical embodiments in bronze, marble, or plaster. The second room focuses on figuration’s relationship to mythology and the divine, featuring a collection of fragmented Greco-Roman figures that represent not only the pinnacle of representation itself but also the incorporation of classical values within the local culture. These imported statues are placed in juxtaposition to a pair of crude indigenous wooden figurines of Christian saints, ostensibly staging a comparison between “high” and “low” culture, but more relevantly, comparing and contrasting distinct uses of effigies. Indeed, the saints are icons, tools for revering and communicating with the divine, symbols more than representations. While the inclusion of a ceramic figurine of a polar bear and a canine made of synthetic wool (Mirosław Bałka’s 1986 Clean Dog…perhaps a domesticated wolf in artificial sheep’s clothing?) may point to a possible animism in sculpture, this emphasis on symbolism rather than representation is most apparent in Marek Kijewski’s (“three the most venerable sisters born of…”) (1994), a triptych made of egg cartons, wild cat fur, rubber, and gold based on the Homeric hymn To Hermes, that poetically describes divine goddesses in the form of bees. Displayed alongside the other figures, the representational potential of the trio of cryptic signs is accentuated, while equally drawing attention to the other objects’ raw materiality as holding deep significance. Jiří Černický’s Phoenixes (2007), also deploys the insect as a model of transfiguration, displaying a grotesque ashtray overflowing with fly carcasses and cigarette butts as an allusion to a mystical regeneration from the detritus of missing personages.

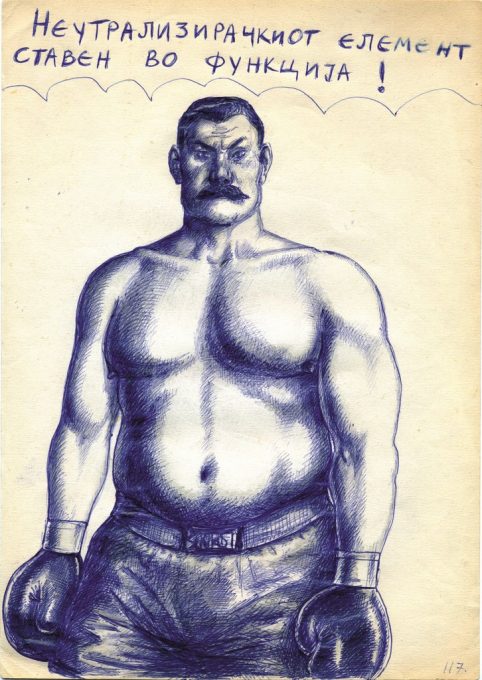

An annex adjacent to the first room features a multifaceted collection of photographs and drawings that also compares different forms of representation, producing a spectrum of chiaroscuro image-making methods and motivations. Refusing the representative power of the photograph, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s two-faced Double Self-Portrait (1974-2009) avoids presence and recognition by averting its gaze, while the Magisters’ A Very High Level of Self-Awareness (2001) features the pair of artists hiding their heads within their shirts, resisting identification through the image just as their non-descript and temporary surroundings deny detail and imply impermanence. All photographs operate as traces of events, figures, and objects that are now absent, becoming both an incomplete index of the momentary past and an autonomous image. This elemental property of the photograph is especially discernible in the commercial images of Jakub Smolski, who used a camera that would first produce a negative that was then re-photographed into a positive print for the customer, a form of image production through double negation. The original negatives kept by the photographer are on display, intermediary images never meant to be seen that invoke an absence in their presence. A doubling of images is also found in a series of stereoscopic German propaganda photographs from World War II. Replicating human binocular vision so as to give an illusion of three-dimensional depth, the twofold images give similar yet different views of German military power, producing a contrived image of reality not unlike the manipulative aims of propaganda itself. This ambiguity of flatness and depth is even more pronounced in the photographic documentation of Olaf Brzeski’s sculpture The Fall of the Man I Don’t Like (2012), where a ballpoint pen drawing was first transformed into a three-dimensional object, only to be flattened again by the photograph. The photograph’s disputable fidelity to history is also a central theme in Agnieszka Polska’s photo series Objects (2007/2008). Manipulated found black and white images featuring puzzling objects installed in uncertain spaces, the photographs suggest the documentation of artworks and records of everyday things, but are wholly independent images, documents without a source.

The artificial truth of photographs, their status as rational and veritable documents, is also contrasted to Stanisław Witkiewicz’s faithful drawings of the landscape. Loose, swift representations of his environment, the artist’s drawings seem even more authentic by disclosing their inherently subjective manufacture. Drawing is a form of storytelling that allows for narratives to be formed adjacent to facts, including not only subjective interpretations and abstract temporalities, but also the story of their creation. In Love (2009), Wojciech Bąkowski even sets his drawings into animated time, but the result is not a linear, chronological story, but rather a set of vague fragments that yield no resolution. While Aleksandar Stankoski’s satirical drawings scrupulously detail grand battles between highly symbolic and prodigious characters from history and popular media, Wilhelm Sasnal’s drawings are ambiguous and partial scenes of non-fictional reportage that each accentuate the inability to represent or narrate tragic occurrences.

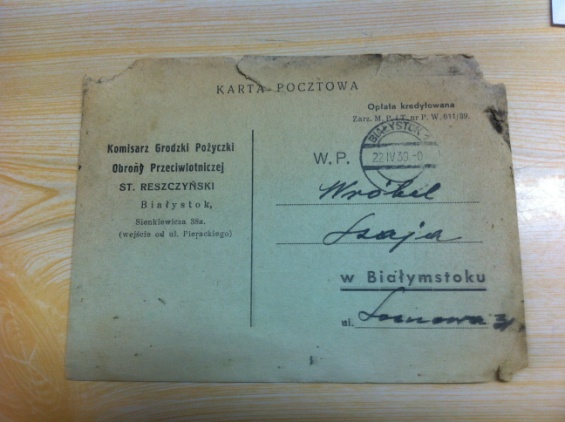

Disputable, subjective, and contingent transmissions of history are also present in another narrow section in the exhibition that concerns archives and their fidelity to memory. Robert Kuśmirowski’s Documents (2001-2002) employ faux aging techniques and antique stylistic conventions to create artifacts without history, thereby elaborating the artifice of recollection and exposing traditional codes used in verifying the past. Juxtaposing these detailed forgeries with real articles, a set of identity documents of past Podlaskie residents bear sets of rationalized facts concerning its diverse inhabitants, serving as official symbols of historical presence. The bureaucratic descriptions of the people are set in stark contrast to an archive of personal documents that give a fragmented and partial narrative of a local Jewish family, demonstrating the stories that are told in personal articles, and making visible the real lives of a community that was decimated and erased from the region. These items are placed in proximity to a selection of propaganda posters that promote the benefits of German occupation, serving as signs for the manipulation of facts and the role of images in justifying ideology. Artur Żmijewski’s video Our Songbook (2003) refers to the immateriality of memory by asking elderly Polish Jews now living in Israel to recall, without any mnemonic support, Polish songs from their childhood. The sentimental yet also hazy and inaccurate recollections serve as testaments to the inexact persistence of memory and language, while also articulating the loss of this culture to the effects of genocide, displacement and time. The relay of idealized and patriotic anthems localizes identity and memory in the body itself, a theme that is also explored in Slaven Tolj’s disturbing Patriot (2007), where the artist repeatedly performs a litany of nationalist gestures and military salutes from disparate regimes, draining the gesticulations of meaning while accentuating their physical endurance in bodily memory.

The embodiment and remembrance of traumatic phenomena is also an essential theme in the third main room. Uncovering an undignified and unsightly facet of lived experience, Iza Tarasewicz’s materialist collection Wounds (2008) presents infected gashes made of pig innards that are halted in a permanent state between injury and recovery. Rendering in three-dimensions a newspaper image Anna Baumgart’s Woman in Mask (2006) points to the superficiality of media representation by giving bodily depth to the image of a bandaged victim in a bombing. In this room, the body is often in crisis, whether in physical or psychological pain, or desensitized and placed into submission, but this operation is also proposed as holding the possibility for rejuvenation or catharsis. The room borrows its title from Oskar Dawicki’s Fruit of Anxiety, Vegetable of Calm(2006), a plant grown from anti-depressants, underlining anxiety and necrosis but also a regeneration. Kuba Bąkowski’s Boy and His Dog (2006) also suggests a struggle and survival after disaster, accentuating both isolation and camaraderie. Fusing the boy and his dog into a single, profane body, Tomasz Mróz’s Self-Portrait (2006) depicts the artist naked and on all fours surrounded by rats. Presenting his own brutish subjection and reverting to a primal and ignominious identity, the artist occupies a state of becoming-animal, not mimicking a beast, but rather atavistically acknowledging intrinsic forces in his own body and mind, charting a zone for desublimation and transformation. Mroz’s savage posture and evolutionary reversion is placed also in comparison to a taxidermied wolf, a wild thing that has been tamed so as to be honored, studied, and preserved. The surface of a now dead creature is reanimated in the museum, but what returns is an imprisoned imaginary, ideological image of what it once was. Vital to both the museological impulse and the scientific method, this process of denaturing, deprivation, and reframing, is equally existent in an inefficacious table fan in Slaven Tolj’s installation Bubo-Bubo Maximus (1994), where the study and preservation of the object, encased by glass and isolated, erases and subdues its function.

Many of the objects in the final room suggest intimate contact with unseemly, uncomfortable, or too-often chastened aspects of private life. Maurycy Gomulicki’s Pussy Mandala (2008) amplifies the decontextualization of women’s bodies in pornography by layering saturated collections of images of genitalia into kaleidoscopic floral and religious motifs, transfiguring exploitation and exhibitionism into ecstasy and enlightenment. Similarly summoning basic bodily origins and spiritual reflection, Ada Karczmarczyk’s bedazzled sculpture Embryo (2013) asserts the preciousness of the small and undeveloped, while also demonstrating that the locus of miniatures is nostalgia for (an imaginary) childhood or origin. A set of small ceramic figurines of young girls likewise relays a sense of nostalgia, kitsch, innocence, and an enclosed, ordered, and uncontaminated world for reflection and relation. The miniatures serve as conduits for affection, but also nostalgia for the (preindustrial) past (of artisanal labor). Fabric handicrafts propagate throughout the room, from Małgorzata Markiewicz’s Flowers (2005) that repurpose women’s worn clothing to produce decorative blooms, to Julita Wójcik’s Lace (2005), a portrait of Galeria Arsenal knitted by the artist that renders and reduces the regal architecture into something soft, palpable, petite, and domestic. Considering objects as companions to our emotional lives, Jiří Černický’s Pincushions (daily voodoo) (2004) suggests that handcrafted miniature objects can allow a simultaneous closeness and distance, abstracting difficult personal phenomena by producing a compact substitute on which anxieties and frustrations from daily life can be expressed. Struggles in the domestic sphere are also visualized in Viktor Marushchenko’s documentary photographs Dreamland Donbas (2004), where the artist depicts moments of beauty and survival in the homes and private lives of impoverished residents of the Eastern Ukrainian region. Comparing kitschy decoration with difficult living conditions, the artist takes a sociological approach, making public private space. Like each of the museums themselves, these images give a complex and distinctive story of their subjects, at once accentuating particularity and universality.

Each room in the exhibition, each set of sets, produces a constellation that heightens certain physical and symbolic properties of the objects and alters their perception.

By mapping sets from distinct collections, the exhibition finds conceptual, material, and aesthetic correlations outside of normalized determinations and engages in an exercise in comparative and hybridized epistemology, exploring the ways language, context, juxtaposition and arrangement modify the expression and circulation of things. Museums do not only display objects, but display the ways in which objects are related to words, themes, ideologies, histories, and concepts: they display systems of representation. The visitor is invited to consider how conceptual schemes really relate to objects, and whether other conceptual schemes are more or less adequate to represent those objects. Combining local collections developed for the benefit of the commons, “Common Sets” gives a subjective appraisal of the values, histories, culture, and concerns of the people of the Podlaskie region, making visible how its institutions represent its inhabitants through objects, and inviting the inhabitants to question the order of things.

The artists taking part in the exhibition include: Mirosław Bałka, Basia Bańda, Anna Baumgart, Kuba Bąkowski, Wojciech Bąkowski, Olaf Brzeski, Jiří Černický, Hubert Czerepok, Oskar Dawicki, Maurycy Gomulicki, Zhanna Kadyrova, Ada Karczmarczyk, Marek Kijewski, Robert Kuśmirowski, Leszek Lewandowski, Piotr Łakomy, Magisters (Hubert Czerepok, Zbigniew Rogalski), Małgorzata Markiewicz, Viktor Marushchenko, Tomasz Mróz, Małgorzata Niedzielko, Agnieszka Polska, Wilhelm Sasnal, Mikołaj Smoczyński, Konrad Smoleński, Aleksandar Stankoski, Iza Tarasewicz, Slaven Tolj, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Julita Wójcik, Artur Żmijewski

Media patrons:

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30