ALEKSANDRA CZERNIAWSKA – A Talk

When I once again watched Ola Czerniawska’s, looking for some point to start my tale about her canvases, a recent and quite well-known book came to my mind – “Pension” written by Piotr Paziński. The book’s main protagonist visits a Jewish boarding house near Warsaw. The boarding house – once vibrant with life – is now populated by shadows, Alzheimer of memories, buried events, echoes, which silence each other only to be unexpectedly enhanced. Following the critics’ opinions, we can treat “Pension” as a literary rite of resurrecting the memory and as the first in Poland voice of the third generation after Holocaust.

And such a standpoint – a literary one – I would like to adopt to talk about Ola Czerniawska’s paintings.

Ressurecting memory

The paintings form three distinct cycles, or circles, which often overlap and comment on each other.

First cycle is of course portraits. Portraits of men and women, adults and children, dead and still living, single portraits and group ones as well – one would want to say family portraits. En face or three-quarter profile, exposed ear, in one’s best clothes, immobile, rigid poses.

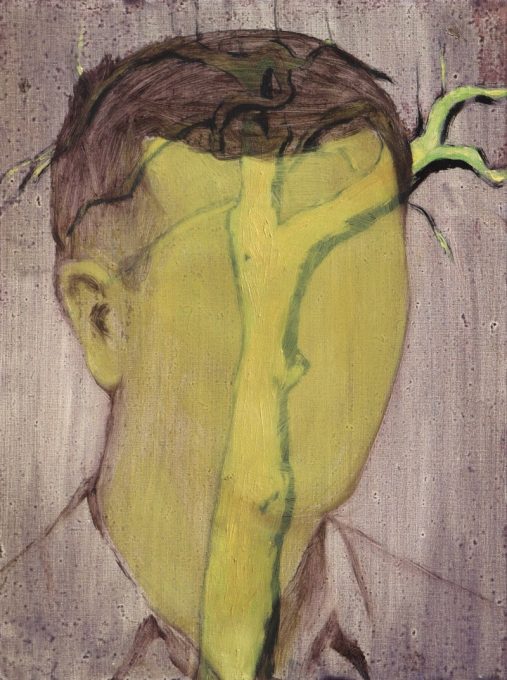

Black and white portraits are dominant, expressive, characteristic; portraits that are enlarged, repainted photos from some old documents. But there are also portraits which break the monochrome convention. However when the colour appears, something obscures the face. The face touched by colour looses its power, hides behind the colour, runs behind trees or into high grass, or into the woods.

Second cycle is of course houses. Ordinary, rural or small-town houses, wooden and brick, with and without porch. Complete houses, with windows, doors, chimney, roof tiles, roofed entrances; but also damaged houses, phantoms, hologram-houses, limited to just a few simplest lines which give them their shape.

These houses resemble portraits. These paintings are portraits of houses. Black and white or in earthy tones, dulled, dirty. The houses’ portraits resemble people portraits in one more way: just like people, houses are characteristic, separate, each happened only once. This is in fact the common ground for agreement between a house and a man: every singe house and every single man happens only this once.

These two portrait cycles – people and houses – work beautifully together, like in the case of „Double portrait” or in the grand “Wedding”. “Wedding” is also a great transition point to paintings forming the third cycle.

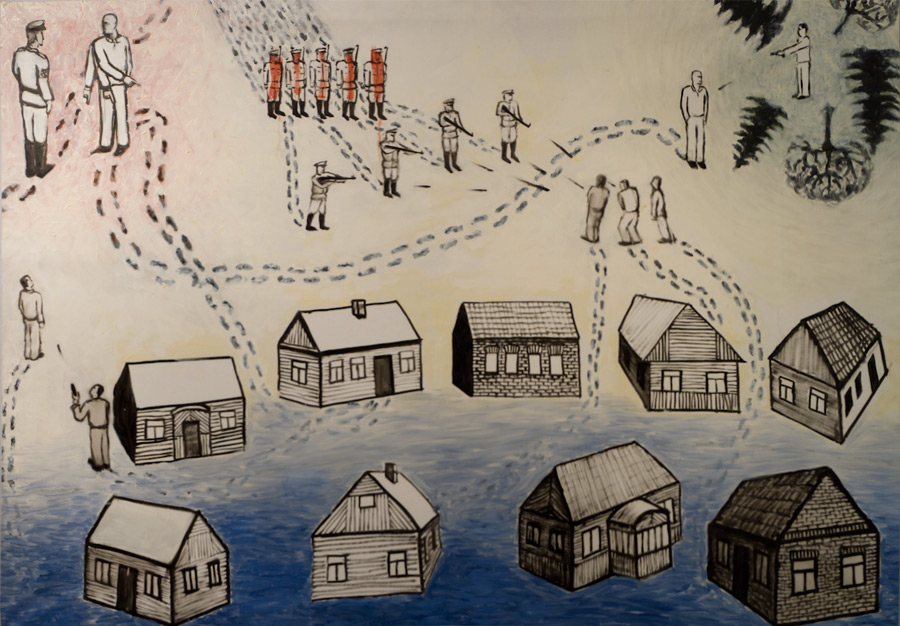

I cannot find a good name for the third cycle. Maybe we can try to call it like this: “Make yourself a life”. Or perhaps differently: “Make yourself a death”. The paintings I am talking about now are the most narrative. Let the example be “Stefan’s Death”. Here we can see houses and people. Someone is talking to someone. Someone is going somewhere. Someone is shooting someone. Someone is putting a gun to his own head. The houses are standing; a barn, a fence. The tree is growing, the roots are growing.

Similarly to sacred narrations, found on Catholic and Orthodox churches’ walls, similarly to ambitious comic book renouncing words – in this case the ball is also on the viewer’s side. Czerniawska provides the viewer with pieces of the puzzle. What story he will tell, what life or what war he will make of it – it is up to him.

I read these three cycles, or circles, as an attempt at resurrecting memory. Memory of war, of people, of houses. What is interesting, war and death are made possible at the intersection of house and man. There is no such thing as an inherent war, war in itself. The only war that exists is a war with people and houses.

One more observation can be added here. A house carries a man within. Several paintings present a cross-section of a building and inside of it – people. This brings to mind – please forgive the obvious nature of this comment – a foetus in mother’s womb. We know what will be born – a man will be born, what we don’t know is – when he will be born. Will he be forced to leave the house prematurely? To exit into the outside world? A world which is not all friendly, not in Czerniawska’s paintings.

Ignacy Karpowicz

______________________

There are moments when Aleksanda Czerniawska’s paintings resemble Emir Kusturica’s movies. She repeats stories heard in the countryside. We go back several dozen years. This is the war and we are in Podlasie. It is a multicultural borderland, the true Balkans of the North. Music is playing at the wedding, vodka is flowing, bullets whistle, brother kills brother, people are dying, bombers drop bombs on cow herds. There is crime, revenge and punishment. There is a Pole, a Russian and a German, and the locals are Belarusian. There are partisans in the woods, Soviets are marching from the East, and there is always one rat in the village that will bring the Nazis.

In Czerniawska’s work there are elements of magical realism, elements of Marc Chagall’s fantasies, which in fact in Podlasie seem to be very apt and worthwhile. The time-space discipline become somewhat relaxed: one man can appear three times on one painting and sometimes there are fish swimming under the village – fish that are larger than the houses.

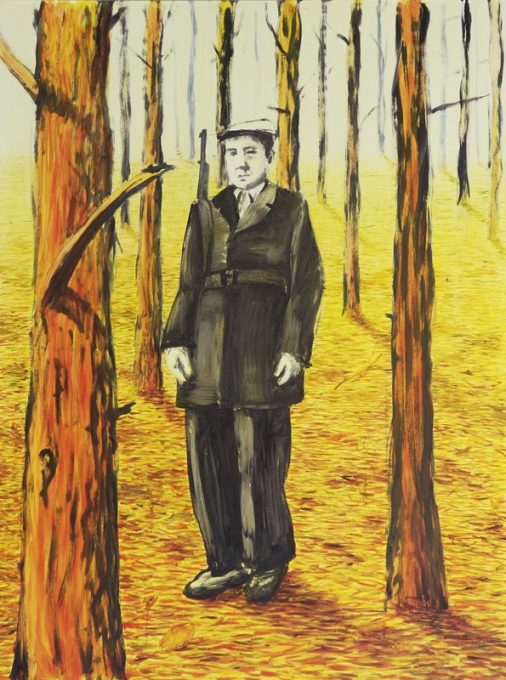

Magical realism takes the floor in order to confront the posttraumatic realism, and then it is Andrzej Wróblewski from the 1940’s, rather than Chagall, that comes to mind. It is no longer about flying over the village – on the contrary, it is about lying in grave. There are many dead among Czerniawska’s characters. In her paintings the dead do not disappear, they remain on the stage, becoming strangely rigid and depressingly serious; when shot they fall like tin soldiers, others lie in coffins and others still seem to be all right, but their expressions clearly shows that they are dead.

*

In Czerniawska’s generation I haven’t seen anyone who would so consciously and deeply utilize painting in order to tell a story. Czerniawska creates a meta-narration, tells stories about stories. She behaves like a post-modern historian, fascinated with oral tradition, local perspective on history, subjective visions of the past. In this understanding of History, it is more important how the events were remembered, not how they “really” took place. That is why the artist listens to the village war stories. About someone who whispered something to the Germans, and this whisper cost some people lives, so there was revenge, a blind shot, through the door, that did kill the wrong person, brother killed brother and then shot himself in the head. These stories were told so many times that they slowly turn into myths; however the last witnesses of these events are still alive. But are they telling what they remember or are they remembering what they told? Czerniawska is fascinated by this uncertainty, because she owns some share of this accumulated capital of memory; these stories took place in the artist’s homeland and are told by her relatives. When the painter pictures the stories, she joins – to some extent – the chain of passing memory from generation to generation. At the same time her actions transgress the clan narration which is the property of a society developing it. The artist moves the story into the area of art, makes it public and universal, and in the subjects it to her own interpretation. She does not want to preserve or distribute the tradition, as much as looks for her own post-memory image in it.

What is this image? Czerniawska creates a heterogeneous visual language, which articulates the discourse developed by the artist in such a natural way that is seems almost obvious – and therefore we can miss its actual complexity. The artist starts a strong, crude figuration, where heavy, simplified characters bring to mind the already mentioned Wróblewski; this way Czerniawska refers to perhaps the strongest visual code that has been used in Polish painting to depict the war trauma. At the same time she puts her paintings’ protagonists in a perspective that is similar to the construction of space in naïve art or medieval religious painting. This (time)space is more multidimensional than the mathematical illusion brought to life by the Renaissance revolution of the linear perspective. In Czerniawska works the painting is not a “window”, it looks more like a text written with ideograms. The motifs of houses, people, trees are treated not as representations but rather as ideograms, which are supposed to bring out words and notions. It is the size of the figures, not their position in the represented space, that defines their place and importance in the narration. On of these paintings’ dimensions is time; in the area of representation the events, which took place in different times, exist simultaneously – similarly to their existence in memory, which encompasses everything at once: causes and effects, “before”, “during” and “after”. Such mode of presentation allows Czerniawska to enter a dialogue with the oral tradition; the artist is not interested how the events took place, but rather how they were remembered – and also imagined; it is the imagination, inextricably connected with memory, which introduces the magical element to the paintings.

Czerniawska takes an ambiguous stance towards the world of Polish-Belarusian borderland which she depicts. It is her world; the artist belongs there genealogically, but at the same time is culturally excluded. She tells the story of a Belarusian village from the perspective of a big-city girl, a professional painter educated at the Academy of Fine Arts in the Polish capital. The author’s complex identity is reflected in the mixed language of her art. This language consists of the lexis of the high modernist painting tradition, as well as local words, taken from the Orthodox icons, syntax of folk art and photography aesthetics. Czerniawska undertakes a multidimensional journey; it is a journey in geographic space, a cultural journey into her private East, but also a journey in time, into the past. This last journey is documented by photos, because the stories which the painter listens to are illustrated by their narrator with photographs from family albums. As a consequence, the visual aspects of memorial photos penetrate Czerniawska iconography. She surrounds complex narrative representations with collections of portraits, depicting real and imaginary heroes of past events. These images, resembling archival photos, are simplified, monochrome; people depicted here are anonymous to the viewers, but in most cases also to the painter. These are the people forming a society of the citizens of the past. Czerniawska is not interested in their identity, but in the emotions related to watching old photos; when looking into the eyes of a person from an old photograph we feel like we are looking into the eyes of the past.

Czerniawska draws us into a stream of memory images, which, right before our eyes, turns into a private myth. Her painting undertaking is ultimately realized when the narration becomes more and more fragmented – and finally falls apart. We reach the borders of a story. Where are they? Between the paintings, which are ever harder to place in the course of history. Among them is a portrait of a partisan standing in an autumn forest, among trees, which have shed their leaves. The melancholic, perhaps even tragic calm of this completely un-heroic figure in an oversized coat is contrasted with a violent color scale, garish oranges and reds – the forest is on fire. Another painting is a landscape without any people, where the trees are almost sketchy, painted with a couple of perfect strokes of red, which turn out to be surprisingly dramatic in the context of this calm representation. There are also portraits of people and portraits of houses, paintings that look as if they were presenting a flooded, underwater world – and paintings which are obscured by one color, like a monochrome mist. Czerniawska’s paintings (almost) always include one winning color, dominating the entire presentation like a camera filter, adding an emotional tone. Polychromatic aspect of the paintings reveals itself only in case of groups of paintings. Czerniawska works not so much with sequences but with constellations of works; relations between individual works are almost as important as the autonomous layout of particular compositions. She creates a kind of unorthodox iconostases; it is important how the painting is presented, not only where. Images of the dead can be therefore placed in the lower parts of the painting installation, and elements which gravitate towards the ground (eg. paintings depicting lying, rigid bodies) are placed directly on the ground.

The painting begins beyond the border of a story heard in the countryside; painting which is still a narration, pictured text, however this history gradually becomes a tale without words, demanding not a literary, but a sensual, intuitive reading. Later in the story the events slowly fade into the background; the main protagonists are now colors, landscapes, places, people and an extremely strong awareness of what was painted. The starting point for Czerniawska’s painting project can be compared to the process of regaining memory; only a full recovery allows seeing and talking about what one sees, allows a personal story to begin.

Stach Szabłowski

translated by Konrad Pormańczuk

______________________

The exhibition was realized with the funds of the Ministerial Program Mloda Polska

Aleksandra Czerniawska

She was born in in 1984 in Bialystok. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw under the guidance of professor Leon Tarasewicz, professor Wlodzimierz Szymanski and professor Miroslaw Duchowski. She works mainly with sculpture and drawing. Czerniawska also creates photographs, objects and installations.

2010

POL-SLOV, Perun, Warsaw, group exhibition

Project Prozna 2010, Warsaw, group exhibition

VII International Festival of experimental art, Exhibition Hall Manege, St. Petersburg, Russia,

group exhibition (co-financed from the Institute of Adam Mickiewicz)

The first person singular, KCCC Exhibition Hall, Klaipeda, Lithuania, group exhibition

Bye, bye love, Galeria Promocyjna, Warsaw, solo exhibition

Dżiga Wiertow – temporary museum, Slendzinski Gallery – Telimena, Białystok, solo exhibition

One Hundred for the Collapse of Art, WizyTUjąca Galeria, Warsaw, group exhibition

Riot, Zamenhofa Centre, Białystok, project in cooperation with Anna Panek

2009

Painting. No frames, 9. Eugeniusz Geppert Competition,

BWA Awangarda, Wroclaw, group exhibition

Syszczyk, WizyTUjąca GALERIA, Warsaw, solo exhibition

Innovation, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, group exhibition

2008

Elektrownia murem, Mazowieckie Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Elektrownia, Radom, group exhibition

Cztery pory roku, Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Ericsson, Warsaw, kalendarz na rok 2009

We wsi…, Galeria Sanocka, Sanok, solo exhibition

Samsung Art Master, Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, group exhibition

Dyplomas 2008, Wytwórnia Wódek “Koneser”, Warsaw, group exhibition

2006

Percepcja Przestrzeni, Galeria Pociąg do sztuki, Warsaw, group exhibition

Project „Warszawa”, work in a public space, Bialystok, solo exhibition

2005

Malarstwo, rysunek, tkanina, grafika, Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Ericsson, Warsaw, group exhibition

Ogrody geometrii, Galeria Aspekt, Warsaw, group exhibition

Aleksandra Czerniawska

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30