Archiwalna

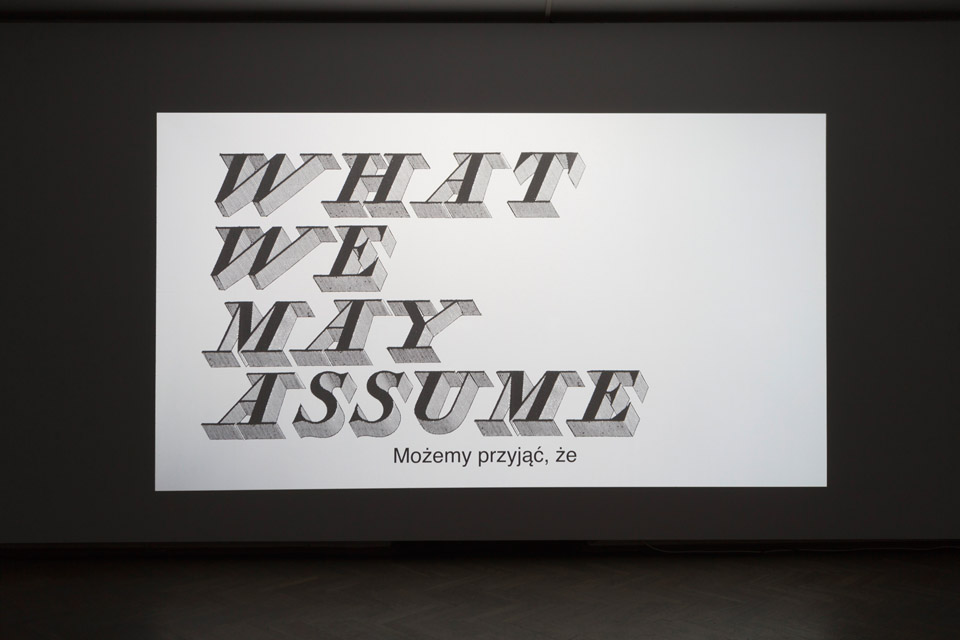

AGNIESZKA POLSKA – In Search of Talking Mountain

15.05.2015 – 11.06.2015

Galeria Arsenał, ul. A. Mickiewicza 2, Białystok

Aldona Kopkiewicz

The magic mountains of Agnieszka Polska

The magic mountains of Agnieszka Polska

The journey to the Talking Mountain was not Agnieszka Polska’s first expedition of this kind; she has attempted to approach the holy and utopian places before. These are the places which promise an encounter with the new and the unknown; which offer an enchanting vision of something that it truly great and alien; places where the ultimate transformation, both of the rules of the reality and the inner side of an individual, is possible. These places promise, seduce and, while they are at it, they deceive. We are essentially aware of this, although we would prefer not to be. The myths of today dwell in different places, mainly on screens, even though the longing

that compels us to turn to them has not changed.

that compels us to turn to them has not changed.

[…] In Talking Mountain Polska also approaches the utopian fantasies of mankind. This time, she attempts to unravel a different magic, the oldest and most terrifying one: the magic of language. Magic itself relies on acting through language, i.e. through spells and incantations, which – according to most of the Romantics and many of the Modernists – have endured in poetry and poeticism itself: in the sound of words and the mystery of images. The essence of this magic was the metaphor, because it was perceived as a perfect intermediary between awareness, words, objects and Nature. The metaphor embodies the faith that the reality has a symbolic dimension

and that Nature communicates with mankind in its own language. […]

and that Nature communicates with mankind in its own language. […]

The journey to the Talking Mountain is an attempt to get in touch with the divine nature, with holiness and mystery that would speak to one and convey privileges, prophecies and superior knowledge. The search for it must end in a fiasco, as it always does in the modern age. Such mountains exist no more; and calling it a “talking”

mountain only depreciates it. The girls setting on this journey are looking for an adventure rather than a revelation of truth, for a meeting with a strange mythical being and not with a lofty and uncanny word. They are, therefore, setting not on a romantic journey, but an Alice in Wonderland trip; but even so they stubbornly cross the lands of perpetual ice, the jungles and the deserts in their search for what is everlasting and indefinite. Importantly, images created by Polska retain their poetic and legendary aspect, while the photographs of mountains turn out to be a joke and prompt a game of looking for similarities which is pure fun.

mountain only depreciates it. The girls setting on this journey are looking for an adventure rather than a revelation of truth, for a meeting with a strange mythical being and not with a lofty and uncanny word. They are, therefore, setting not on a romantic journey, but an Alice in Wonderland trip; but even so they stubbornly cross the lands of perpetual ice, the jungles and the deserts in their search for what is everlasting and indefinite. Importantly, images created by Polska retain their poetic and legendary aspect, while the photographs of mountains turn out to be a joke and prompt a game of looking for similarities which is pure fun.

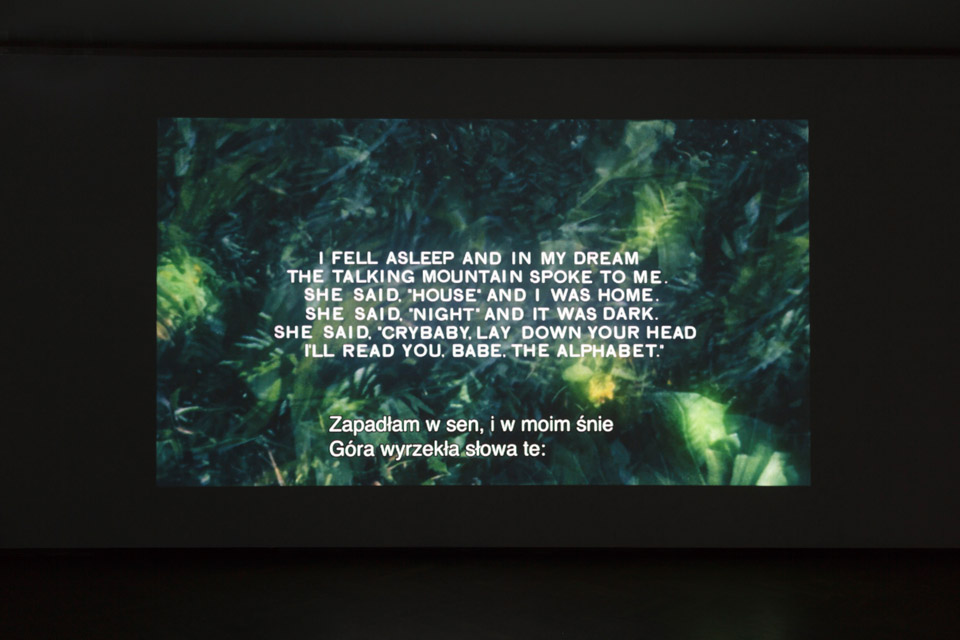

Correspondences have nothing to do with any spirit of the world, and the mountains are smiley or sad if faces are drawn on them. Nature is silent; but the girls continue on and despite their light-hearted attitude they are looking for their Mountain in earnest. A change of mood is introduced in the last scene, with the return to the jungle where one can fall asleep and never wake up: the droning waves of sound are like the mythical sirens who lure the unwary into the world of dream or ecstasy. The voices of the heroines fall silent, all that remains is a caption: a short childish rhyme about the Talking Mountain, which is still capable of magical gestures, but only in people’s dreams. Yet this magic has little to do with a mysterious code or metaphysical voice; after all, the mountain foreshadows the reading of the alphabet. This individual desire is nevertheless suppressed and erased; instead it, conventional writing endures just fine, combined with the image of nature; they are two mirror-image totalities which do not allow an individual voice to intermingle with them.

Undaunted, Polska returns to her dream, although this time she begins with art and with the thing which in language is the most human yet the most alien: the mouth. The short animation I am the Mouth II (2014) shows full, bright-pink lips half-submerged in water. They would probably be sensual if not for their digital artificiality. The upper lip rises from water like an iceberg, the lower lip, submerged, seems to be stiff from cold. I have no idea whether the water was really cold, but I had this impression from the very beginning; this is because my association with a drifting glacier was way too powerful.

The contrast of colours between the upper and the lower lip, between red and blue, illustrates the ambivalence of emotions triggered by a mouth: they are for receiving food and love, for sucking at the mother’s breast, for kissing – and from this, it is but a small step to greed, to devouring and sucking dry. They are the origin of voice; but if we watch a talking mouth for a while – as in Samuel Beckett’s famous dramatic monologue Not I from 1973 – we see the white teeth and the black nothingness that fills the throat. Language, after all, should not derive from the bodily matter only; this crucial gift, no matter whether divine or human, but always one that distinguishes us from animals, should not originate from worthless organs. With Beckett this awareness was still a frightening one, and it required a sharp and affecting expression.

Polska shows a simple and nice image of the mouth. This is a mouth without a throat; there is only water between and around the lips. This mouth is more inhuman than Beckett’s mouth; and yet it is a pleasant mouth.The image begins to seem distressing only upon noticing that its passionate sensuality is expressed in artificial and cool colours, and the warm voice emerges from a space created by a poster-like composition without any depth. The mouth speaks in soothing tones, like a mother’s mouth. This, again, is associated with sensual pleasure, ice-cold and scorching at the same time. The mouth speaks of uttering sounds – waves and vibrations that disperse upon the sea. The sea signifies the network of social relationships, but its depth is again revealed as an expressive metaphor for what is not yet expressed in the language. The inexpressible, however, does not cause pain or arouse desire. The soothing voice of the sea inspires an intuition that the hidden potential would ultimately be revealed.

A certain fantasy about the language per se is materialised in this animation of a mouth: that it is as the waves going from nowhere to nowhere; that it is an all-knowing and all-seeing awareness which is nevertheless unable to utter a word. The image of the omnipotent language, even as an invisible system that shapes us, perfectly resembles the divine omnipotence which is nothing else but motherly love. Both of them offer the tempting possibility of dissolving, of losing one’s individual being in some vast entity. The system of the language usually arouses fear and distrust; here, however, this linguistic abstraction is endowed with the quality of a soothing soak in a bath. The well-known oceanic metaphors are transferred onto the seemingly nice and innocent digital image; in effect, we submit to the pleasant motion of waves aroused by the voice and we get slightly hypnotised by gazing upon the gently moving mouth. Listening intently to the soothing feminine voice, we begin to trust the very act of speaking, the pure language, even if that voice tells us that it can barely breathe. The perfectly composed frame is the symbol of the power of the language and also a warning that the image and sound can easily soothe and lull us to sleep, and thus to annul any contents that could be expressed, or word that could be pronounced by an individual person.

The tropes of water and motherhood emerge also in the Watery Rhymes, at least in the title. This animation has a very different rhythm and montage; it resembles a music video. Here, words emerge like poetry created by an individual person; but since the language has only the earthly, bodily aspect, Polska finds for it a different, secular magic, which is science, and more precisely: quantum physics. The film begins with captions which overlap in a way that makes their material aspect more tangible and more massive; finally the captions obscure the contents. The contents, in turn, has an ironic meaning in this juxtaposition; this is because what we are dealing with are the constantly moving language particles, words which travel the world in accordance with the quantum laws of Nature. The qualities of words are therefore indefinable but perceptible, and the “I” is surprised not so much by the alienness of the language, but by the feeling that in one’s mouth it turns so familiar. Everything seems to float and to dissolve, this time in the air, and yet, in a reality described in this way, concrete words and images emerge to transform this animation into a poem.

The captions are interrupted by the image of a glass filled with a liquid; its opalescent colours indicate that it is petrol, which will soon be spilled on the sea and will carry the words upon its waves. It may also be various paints poured into a glass. The intensity of colours brings to mind psychedelic patterns, so it could just as well be some magic brew. After a while, the captions float upon the water and disperse like waves, but rhymes hold them together.

Their rhythm is broken by succeeding images; I would say that they are metaphors, but by now Polska is showing us only objects and pointing to their materialness, even though they do not exist outside the digital medium. Nevethelss, seen in short constellations, they evoke the questions not only about the prospect of sentiment, but also about the prospect of attaining human relationships in a world devoid of empirical values. The indiscernible materiality of the physical world may find expression in the utopia of virtuality, but then that special yearning for the presence of another human being recurs.

It is for this reason that Polska closes her film with a love poem, where she tells her lover that he, too, consists of still-undiscovered words, quantum nouns and micro-adjectives; yet she discovers in him the desired unity: the body of words. For that reason she repeats the rhyme of the last couplet like a spell, building a tension between the single body and the body of words, between a text and a corpus, so that the fulfilment she experiences does not dissipate in the air: “I can’t count your body’s words. / The body of words. / The body of words”. The body of the beloved man is perceived as uncountable and impossible to count on, incomprehensible and infinite, but also as material, tangible and singular. Only in this relationship does the innumerability of words begin to hurt. But Polska does not reveal anything in her own voice; this poem is recited by a voice filtered through a synthesiser. It does not sound artificial, however; it speaks tenderly, even though love itself, when seen from afar, is beautiful like a carpet of sea anemones which seen from a different angle changes into a death’s head. Such a voice reinforces the words and images, since they do not need the testimony of the loving woman; they need the artistic means. The body of words and the body of the lover finally meet, because they are sustained by the archaic, musical magic of poetry. They are produced by writing and the digital image, rhymes and repetitions, i.e. by the artistic media – that final resort of the contemporary and yet still elusive magic.

translated from Polish by Klaudyna Michałowicz

fragments of the essay which will be published in the catalogue of Agnieszka Polska exhibition “In Search of Talking Mountain”

Curator: Agata ChinowskaAgnieszka Polska

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30