Nikita Kadan

“Chronicle” cycle

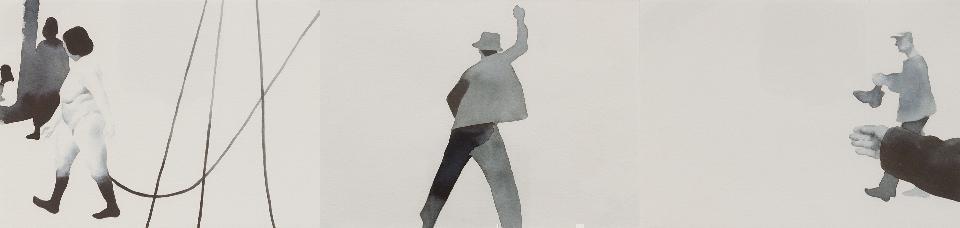

Nikita Kadan, 3 drawings from the Chronicle cycle, 2016ink on paper, 17 × 24 cm

Collection II of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok. Work donated to the Arsenal Gallery by the artist in 2021

Drawings from the Chronicle cycle by Nikita Kadan should be viewed as a reflection on Ukraine’s identity, on the recollection of the dramatic events of the last century, and on the ongoing disputes concerning the past. The sphere of Kadan’s considerations also includes Poland, the difficult Polish-Ukrainian relations and historical conflicts relating to the events in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia in 1943–1945. The drawings are based on solid source material: texts and photographs documenting Nazi crimes, murders committed by the NKVD, the pogrom against Jews in Lviv in 1941, ethnic cleansing of the Polish population by the nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army and the revenge on the Ukrainians wrought by the Home Army soldiers.

On white cardboard, in black ink, Kadan reproduces parts of indeterminate scenes. They are suspended in a void, indistinct and devoid of detail. Kadan evidently focuses his attention on the victims: with a skilful motion, he renders the inertia of people killed, hanged, huddled together, raising their hands in a gesture of defence. The de-contextualisation and recourse to the lightweight medium of ink serve to aestheticise the representations, but do not deprive them of their import. The scale of the depicted cruelty emerges from under this soothing filter and strikes the viewer with full force. Kadan asserts the stance of an objective observer, looking at the photographs and history directly. This approach echoes a cautiousness towards the source: it was not uncommon for the interpretation and attribution of photographs to be manipulated for propaganda purposes. As historians’ research has shown, following acts intended to obliterate the traces of a crime, it is not easy to identify people buried in mass graves, to determine their national or ethnic affiliation or to establish their role in the terrible events. Kadan’s drawings are similar in this respect: it is not clear whether what we see are executioners or victims, men and women of Polish or Ukrainian ethnicity. The title of one of the drawings says it all: A Pogromist Looking Like a Revolutionist. Discovering the truth is not easy.

Based on archival resources, Kadan’s works move away from a history based on facts or revisions. Kadan tells of history through the silent bodies and experiences of the victims. His drawings take on a new dimension in the context of current political events: the Russian annexation of Crimea and the open military attack on Ukraine. The Chronicle inevitably suggests that no lessons have been learnt from the events of the past.

Izabela Kopania

translated from Polish by Klaudyna Michałowicz

Pogroms and Massacres Are a Thing of the Past

I told Kadan once of a meeting in Bykivnia, a military area and a burial ground for victims of 1937–1938 Stalinist terror, army officers murdered in Katyn in 1940, and – possibly – post-war victims of the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs). I had just finished Archeologia zbrodni. Oficerowie polscy na cmentarzu ofiar NKWD w Charkowie [The Archaeology of Crime: Polish Army Officers Buried at the NKVD Victims Cemetery in Kharkiv], a book by professor Andrzej Kola. I had also attended a meeting with the author at the exact location where he managed works preceding the official opening of the Polish War Cemetery in September 2012; this was the fourth Katyn cemetery forming part of the Bykivnia Graves Memorial. The professor talked of features allowing victim identification; of how soldiers could be identified by their buttons, boots, epaulets, and uniform details. In his book, Kola describes post-war efforts of Soviet authorities to cover all traces of past crimes. He writes about soldiers – who else could have been put to such work – digging through burial caves, moving human remains, planting trees, and spilling chemicals to dissolve all organic matter. Yet not all toothbrushes, leather soles, pieces of documents and spectacles could be removed. When asked whether Polish archaeologists would also take an interest in Polish civilian victims of the 1930s (Poles had been one of the first groups repressed for nationality reasons in the USSR), the professor responded that it was impossible to distinguish them from other Soviet citizens because they had bought identical knitwear and accessories as the rest. “Bones got mixed together”, the professor said.

The Bones Mixed Together («Кістки перемішались») exhibition, its title given by the story above, realised in August 2016 at the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok, focuses on victims of mass Nazi and Stalinist murders, of the ethnic cleansing of Poles by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and of Home Army revenge attacks on Ukrainians, of the 1941 pogrom of Jews in Lviv, and of all Nazi crimes in Lviv. The scope is extremely broad. It goes without saying that reading Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin is an excellent introduction to the exhibition. The artist himself quotes Yaroslav Hrytsak: “Ukrainians are united by their victims rather than by their heroes.”

Kadan pays close attention to victims. His works take on weight and volume through action taken by historians and through the white bones of victims. All is chiefly attributable to the war that eastern Ukraine suffers of. Foaming, history spills beyond the frame of monuments designed for purposes of remembrance. It cracks and disrupts the valour of heroes and the good fortune of chance civilian survivors – concocted of concrete and Styrofoam, intolerable in clichés and manipulation yet efficient in displacing uncomfortable memories. The field of remembrance swells, blushing with the contemporariness of daily experience. Kadan’s activities comprise an alternative perception of the past coupled with an awareness of simplifications used by an array of community, public, private, and state-owned institutions attempting to force-feed societies with their comprehension of history. Moreover, his artworks are a reminder of how much the environment and experience form and shape the imagination. In the artist’s earlier works, the human body was oppressed and yet survived. Once pro-Russian terrorists struck eastern Ukraine, Kadan began conjuring up bodies of the deceased. So extraordinary and unsullied. Nobody knows what to do with them yet save a gentle cover of branches or newspapers, offering some intimacy in early death. They have not yet begun vexing the living with their numbers, their odour and their demand for time and strength that are necessary to survive during wartime. The drawings are subtle.

The artist: “While all images are suspended in a vacuum, each trails severed threads of context. When selecting the next photograph – and the next – I follow the assumption that documentary photographs have to be perceived directly, in full awareness of one’s own incomprehension and of how easily one’s perception may be manipulated. We have to perceive history directly rather than through a looking-glass shield of ideological mythogenesis.”

I know not whether one can indeed afford a direct gaze, truly suspending one’s own beliefs. The artist makes such attempt. In some drawings, all attributes – uniforms, clothing allowing indubitable classification (what if someone used a disguise?) of the victim and the perpetrator by nationality and ethnic group – vanish. And such is the fate of mass graves under conditions of shortage of funds for horribly expensive genetic testing. Yet the origin of the individual as a member of a species never vanishes. The details and context can be reconstructed on the basis of historical photographs still in circulation, their attribution periodically modified. Everything else is reduced. There is no architecture, there are no weapons, there are no objects. All that remains are spatial relations and the aesthetic uniformity of those standing and watching and those prostrate and slowly decomposing.

The beauty of Kadan’s works momentarily suspends the content of all the images of our human inter-species naked cruelty. We are handed an aesthetic filter. We gaze upon the pretty. The horror of the renderings reaches us in time – only then do we begin ruminating upon the context.

An acquaintance of mine once said that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in 1948 simply because mankind recovered, cooled down, and was terrified by its own self. The right to life, the most important one of all, is occasionally suspended by a variety of institutions: the state, the police, or the army – but also by revolutions, rebellions, and ethnic cleansing. Now that seventy years have passed, would you reiterate a pogrom of Jews? Of Poles? Of Ukrainians? Of gays and lesbians? Of Gypsies? Of refugees? Would you react when witnessing a pogrom of Jews? Of Poles? Of Ukrainians? Of gays and lesbians? Of Gypsies? Of refugees?

Such is our condition today. Such are questions ground by mills of social networks and the press, uttered in hate speech raised from the dead 1930s. Hate speech that is used in public space, hate speech that public institutions do not react to. Kadan does not ask his questions so persuasively, he refrains from arm-wringing or procuring institutions to act in case. In his own balanced manner, he weaves a fabric of reflection on the creations of our daily social life – on necro-politics and on the need to manipulate images of bones and victims. The perspective is one we have a profound need for – it allows us to work and analyse our own traumas. And to give serious thought to what we are capable of today as inhabitants of the bloodlands.

Zofia Bluszcz

translated from Polish by Aleksandra Sobczak

An excerpt from the essay ‘Topics and Places Ready for Silence: Here and Now’ by Zofia Bluszcz, published in the exhibition catalogue Nikita Kadan. Kości się przemieszały / Bones Mixed Together, Galeria Arsenał, Białystok 2016

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Opening times:

Thuesday – Sunday

10:00-18:00

Last admission

to exhibition is at:

17.30